Created by Henry Stratman on Mon, 10/14/2024 - 22:04

Description:

John Bunyan's 1678 allegory The Pilgrim's Progress is among the most influential and consistently circulated books ever written. Widely printed and often lavishly illustrated, copies of The Pilgrim's Progress could be found all across the globe during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. English author and preacher Bunyan began writing this tale while imprisoned for his religious beliefs, creating a narrative that reflects his understanding of the trials and perseverance of a Christian life. The story follows the character Christian, who is burdened by the terrible weight of sin and is driven by a deep desire to reach the Celestial City, representing Heaven. Christian's adventures are organized into neat episodes in which he encounters various characters and obstacles, each symbolizing specific virtues, vices, and spiritual challenges. Along his journey, Christian meets figures like Evangelist, who guides him; Faithful and Hopeful, who journey alongside him; and Apollyon, who stands as a fearsome adversary. In each encounter, Bunyan's audience learns lessons about faith, endurance in the face of despair, and the universal struggle between good and evil.

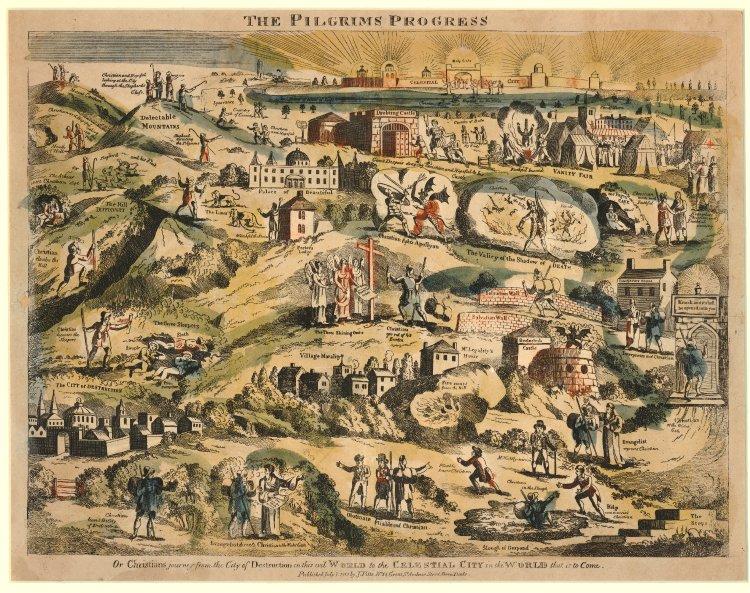

John Pitts, hand-colored print of The Pilgrim's Progress (1813), The British Museum. The Pilgrim’s Progress (1878, 1684) recounts the story of Christian, a man burdened by the knowledge of sin, and his journey along the winding path to the “Celestial City,” beginning with his escape from the “City of Destruction.” The tremendous popularity of Bunyan’s work among both children and adults implied an interest in artwork and revised editions of the text. Maps were produced to show Christian’s adventure, such as this hand-colored etching published by the English artist John Pitts in 1813. Each landmark represents a moral or spiritual challenge that Christian must overcome, symbolizing the spiritual experiences of faith, temptation, and redemption. Art like Pitts’s served as a guide for readers while enhancing the narrative’s accessibility, enabling it to resonate visually with a wide audience.

"John Bunyan," line engraving by John Sturt, late 17th to early 18th century, National Portrait Gallery. John Bunyan (1628–1688) was an English writer and preacher, best known for his classic allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress. Born in Elstow, Bedfordshire, Bunyan came from a modest background and received limited formal education. During the English Civil War, he served briefly in the Parliamentary army and worked as a tinker like his father. In 1653, Bunyan became profoundly interested in religion. His fervent preaching led to several arrests after the Stuart Restoration when religious gatherings outside the Church of England were prohibited. He began writing The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) during his imprisonment. Strut depicts Bunyan in the austere, modest clothes typical of a Puritan.

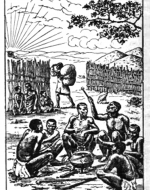

An African Version of The Pilgrim's Progress, 1902, Wikipedia. At one time second to only the Holy Bible in popularity, The Pilgrim's Progress is among the most impactful and wide-ranging books ever published. It has been translated into over 200 languages in the three centuries since it was written. Much of its global popularity stems from its use by Christian missionaries in Asia, the Americas, and Sub-Saharan Africa, where its accessible allegorical style and universal themes of faith, perseverance, and redemption resonated deeply with diverse audiences. This illustration comes from a version of the story printed in Africa. By portraying Christian as an African man, the illustrations allow local readers to more easily identify with Christian’s journey and ordeals. The visual representation aligns the character’s story with their own cultural context, making the narrative feel more personal. This approach recognizes that the universal themes of The Pilgrim’s Progress—faith, perseverance, and redemption—transcend specific cultures, and connecting these themes visually to local cultures deepens engagement.

George Woolliscroft Rhead, illustration titled "Christian Battles Apollyon," 1898, Library of Congress. Christian must pass through the Valley of Humiliation during his journey to the Celestial City. This kingdom is ruled by the monstrous Apollyon, a demon who will stop at nothing to keep Christian, whom he sees as his rightful subject, trapped within his domain. Apollyon tries to discourage Christian by pointing out his sinful past and telling him that he is unworthy to enter the Celestial City. The demon argues that Christian would indeed be happier if he were to turn around and return home to his old life and family. When it is clear Apollyon will not succeed in deceiving Christian or weakening his resolve, he attacks. Rhead depicts this tense scene in his illustration. He interprets Apollyon as a creature of darkness and chaos, using demonic and monstrous imagery. Apollyon's imposing, grotesque form represents sin, temptation, and spiritual opposition. Although Christian is much weaker than his assailant physically, his reliance on faith and God's grace allows him to triumph over the monster. The illustration reinforces Apollyon as a terrifying enemy that embodies the forces of evil, making Christian's victory seem all the more miraculous.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Featured in Exhibit:

Artist:

- John Pitts