Created by Catherine Golden on Mon, 03/01/2021 - 22:40

Description:

The ideology of childhood sin influenced literature given to children well into the early 20th century. Lining the Victorian nursery shelves were cautionary tales written in the 17th to the 19th centuries informed by the doctrine of original sin--Adam and Eve's eating of the forbidden fruit in the Book of Genesis. Works by didactic strongholds-- James Janeway, John Bunyan, Isaac Watts, and Mary Martha Sherwood--aim to teach children to be good via an “awful example” to scare them into obedience. Even as the ideology of childhood innocence gained prominence as the nineteenth century progressed, the didactics retained popularity in the Victorian schoolroom. The vivid and dire consequences of disobedience in the works by all four authors spanning three centuries are shocking to readers today. As this chronological arrangement of authors reveals, the degree of didacticism in a work does not decrease over time. While Watts offers a gentler mode of instruction through his divine songs than Janeway or Bunyan do in their respective works, Sherwood, who quotes Watts, recalls the fervor of Janeway though writing well over two centuries after him.

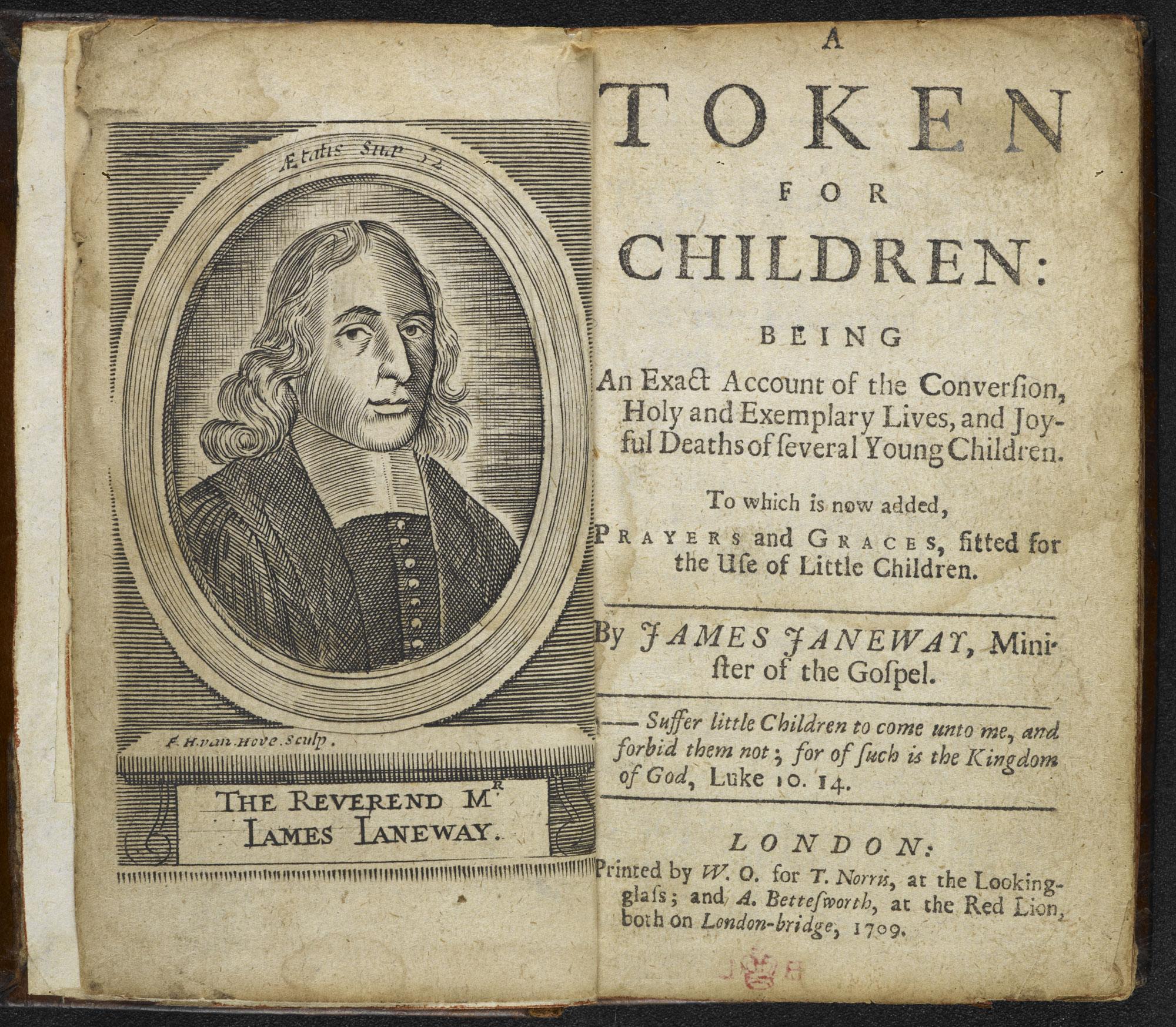

James Janeway, Frontispiece and Title Page, A Token for Children (1672), 1709 edition, The British Library.

Janeway, a Puritan minister, recounts the joyful deaths of 13 children in his account designed to save children from Hellfire and offer children a means to reach heaven. To Janeway, every child was born with original sin; only strict piety and repentance could assure children's salvation. In the preface, Janeway chillingly asks a series of rhetorical questions: "Whither do you think those children go when they die, that will not do what they bid, but play the truant, and Lie, and speak naughty Words, and break the Sabbath? whither do such children go, do you think?" Janeway then answers the questions: "Why, I will tell you; they which lie, must to their Father the Devil, into everlasting Burning; . . . and when they beg and pray in Hell-Fire, God will not forgive them, but there they must lie forever." That Janeway's popular book was still in print in 1875, over two centuries after it was published, speaks to the endurance of the didactic tradition in children's literature.

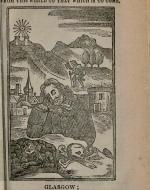

Title page, Pilgrim’s Progress (1678, 1684), by John Bunyan, 1840 Chapbook edition, National Library of Scotland.

This two-part Christian allegory by Bunyan, an English minister and Noncomformist preacher, follows the journey of Christian, an everyman figure, as he undertakes a pilgrimage towards salvation. We cannot underestimate the importance of Bunyan's religious allegory. Next to the Bible,Pilgrim's Progress was the most common text found in a Victorian home. Still in print today, it has been frequently reprinted and translated into over 200 languages. The title page comes from an early nineteenth-century chapbook edition, which abridges Parts I and II of Pilgrim's Progress into a mere 24 pages. This edition features illustrations that highlight the many challenges Christian faces on his jouney to the Celestial City. In the foreground is a representation of Bunyan dreaming of the tale that will unfold in this progress; behind him is Christian, the pilgrim, making his way to the Celestial City featured in the upper-left corner, and below him are a skull and lions, perils that Christian encounters on his way there.

R. Barnes, "The Vain Child," for "Song XX. Against Pride in Clothes," for Divine and Moral Songs for Children (1715), by Isaac Watts, 1866 edition.

Isaac Watts, like James Janeway and John Bunyan, was an English minister as well as a hymn writer. Watts's work, composed of Divine Songs and Moral Songs, aimed to teach children many of the same lessons as the other didactic writers--not to be vain or idle, not to quarrel or lie, not to steal, and to be God-fearing and dutiful. Watts was aware that the rhyming format of his poems, referred to as songs, would soften the didacticism and make the lessons more palatable to children and easy to remember; he notes in the preface: "What is learned in verse is longer retained in memory, and sooner recollected. The like sounds and the like number of syllables exceedingly assist the remembrance. And it may often happen that the end of a song, running in the mind, may be an elfectual means to keep off some temptations, or to incline to some duty, when word of scripture is not upon their thoughts." Some songs do refer to Hellfire and Adam and Eve's original sin, including "The Vain Child" illustrated by R. Barnes (one of several artists illustrating this edition of Watts's book of improving verse). From the tilt of her head to her fancy clothes, the pretty child exudes vanity, considered one of the deadly sins. Today Watts's verses are best known through parodies by Lewis Carroll, who in Alice in Wonderland (1865) transforms Watts's industrious bee in "Against Quarelling and Fighting" into a lazy crocodile. But other didactics quote his poems verbatim, such as Mary Martha Sherwood, who incorporates Watts's improving verse in some of her stories in The Fairchild Family.

Florence M. Rudland, "At Last She Fell Asleep," for "The All-Seeing God," in The Fairchild Family (1847), by Mary Martha Sherwood, 1902 edition.

Mary Martha Sherwood’s The Fairchild Family (1818, rev. 1847) was a popular Sunday School prize book well into the 20th century. In "The All-Seeing God," Sherwood, a minister's daughter, tells the story of Lucy Fairchild, who takes damson plums from a jar in a storage closet and falls ill as a consequence of consuming the forbidden fruit. Lucy recovers, realizes her sinfulness, and confesses to her mother: "'what a naughty girl have I been! What trouble have I given to you, and to papa, and to the doctor, and to Betty! I thought that God would take no notice of my sin. I thought He did not see when I was stealing in the dark. But I was much mistaken. His eye was upon me all the time. And yet how good, how very good, He has been to me! When I was ill, I might have died.'" Florence Rudland captures Lucy in the throes of a high fever at a point in the story when the doctor believes she may die. Lucy recovers to repent her naughtiness, but the illustration lingers on the possibility that due to her stealing, Lucy might easily have died. Other stories do include the death of children as a consequence for for their disobedience. In "The Sad Story of a Disobedient Child," vain Augusta Noble looks in the mirror, despite her parents' warning, and catches on fire from the candle she holds to admire her reflection. Sherwood describes graphically how Augusta dies in agony. In Sherwood's "The Story of the Sixth Commandment," Mr. Fairchild--apalled that his children are fighting--takes all three of them to see a man hanging from a gibbet as a consequence for killing his own brother. Sherwood in this story also quotes two stanzas from Watts's "Against Idleness and Mischief" to drive home her point that children should not, in Watts's words, let "angry passions rise" or "tear each other's eyes." Didacticism has a sharper edge in this Sherwood story written two centuries after Watts's immproving verse!