Created by Gentry White on Tue, 10/11/2022 - 18:33

Description:

The 19th century was a period of both innovation and devastation in the public sphere of health and hygiene. During this time, the average life expectancy for the middle-class man was 45 years, and half as long for workmen and laborers. Many children died in infancy due to exposure to toxic substances, disease, accidents, and more, meaning that “nearly one infant in three in England failed to reach the age of five” (Douglas). Medically trained professionals still operated under some misconceptions like miasma, or the belief that disease transmission was “a matter of inherited susceptibility (today’s genetic component) and individual temperance (lifestyle)” (Marsh) rather than environmental factors like water. The average household contained a great many toxic and dangerous materials thought to be safe for consumption, topical use, or even decoration.

There were many factors that played into health and hygiene in the Victorian era. With the boom of population in England, specifically in London, an increasing amount of worrisome diseases like cholera, influenza, typhus, typhoid, and tuberculosis emerged in waves. There was a general disparity in health between the wealthy and the poor. “The poorer classes, being underfed, were less resistant to contagion” (Douglas), though disease did affect everyone regardless of status. Those who could not afford high-end doctors in turn sought after “quacks” or “quack medicines” (Picard). Many “fashionable charlatans” made incredible lives for themselves in the Victorian era by claiming to hold the key to cures for almost everything ranging from typhus to tuberculosis. One individual in particular named John St. John Long “claimed to cure consumption by liniment and medicated vapors.” Ironically enough, he died at the age of 36 of the very thing he was said to have cured.

There was a surge of innovation in regard to sewage and a wide spectrum of legislation and community engagement aimed at drastically improving health and hygiene. A few of the principal acts passed in the 19th century included the Baths and Washouses Act of 1846 and 1847, Towns Improvements Clauses of 1847, and Public Health of 1848. The Public Health Act of 1848 came about by Edwin Chadwick, an architect involved in the 1834 Poor Law (made seeking provision of poor relief so unpleasant that it deterred people from doing so) who argues that “if the health of the poor were improved, it would result in less people seeking poor relief.” After another outbreak of cholera in 1848, Parliament was forced to respond and the Act was passed. It established a Central Board of Health, and formed corporations meant to “assume responsibility for drainage, water supplies, removal of nuisances and paving.” It also sanctioned the burial of the dead, as there were so many deaths during this time, that the proper disposal of corpses had not really been a true priority unless otherwise specified by those wealthy enough to afford it.

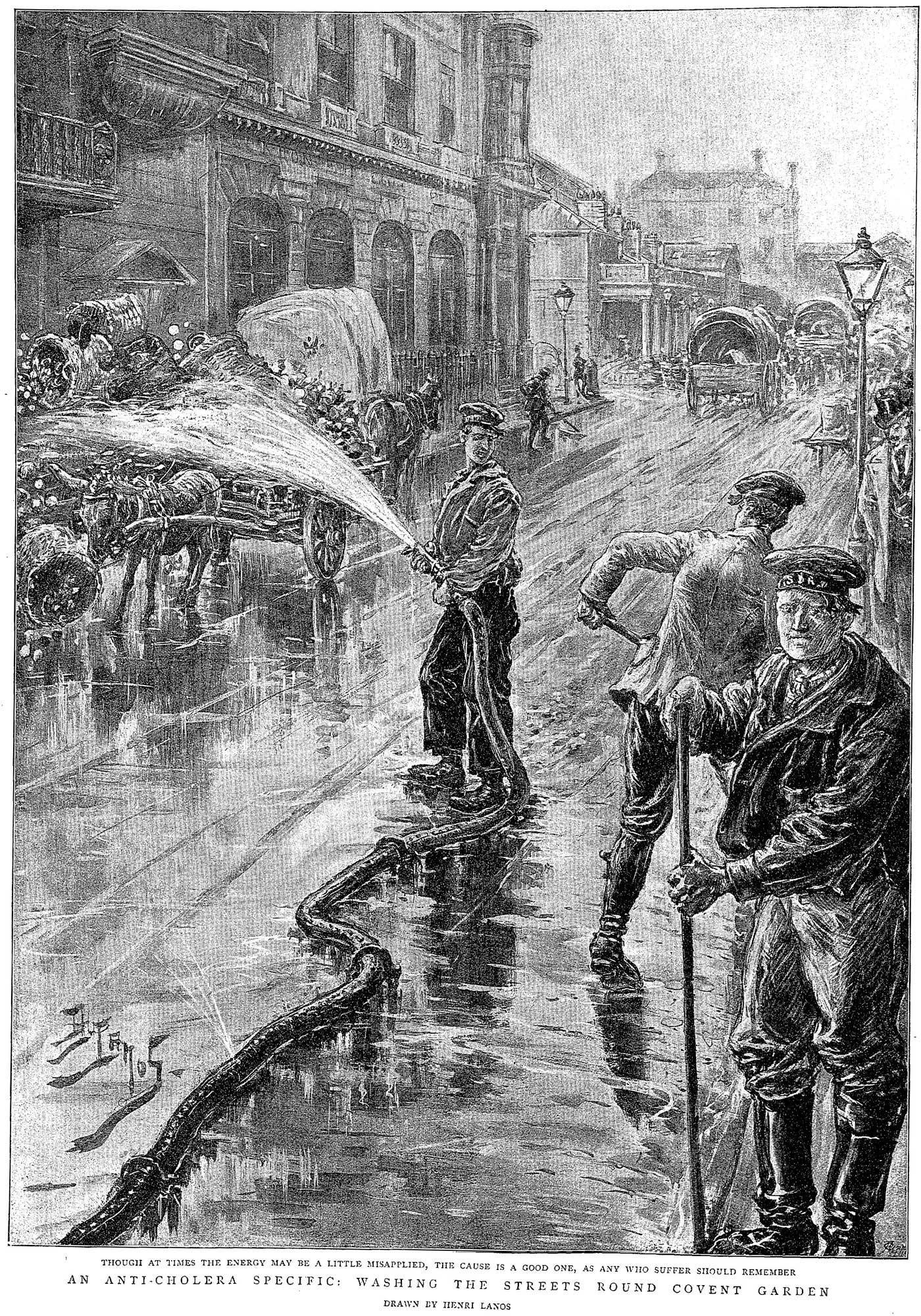

John Snow, a physician and leader in the development of medicinal hygiene, attempted to dispel the theory of miasma and illustrated the correlation between unclean water and cholera. His demonstrations helped “push forward projects to provide clean water, separate sewage systems and rubbish removal in urban areas, as well as to legislate for improved housing - one goal being to reduce overcrowding” (Marsh). During this time as well, the building of sewers and the invention of a flushing toilet helped work toward the decrease in numbers affected with disease. Water closets were becoming more common to have inside the home. There were efforts to clean the Thames after the “Great Stink” of 1858, as well as people scrubbing the streets outside Covent Garden in hopes of cleansing the neighborhood of cholera. This image is provided for the gallery and is an illustration by Henri Lanos for the 1894 newspaper article titled, "'An Anti-Cholera Specific: Washing the Streets Round Covent Garden."

Overall, the Victorian era was definitely an interesting time to be alive. For a toothache, one would take laudanum or opium in lethal doses, even giving such substances to their children when they were finicky. Bread was often made with a poisonous substance called alum, and green wallpaper was found to contain arsenic. It was during this time, though, that scientific innovation shed light on the elements of everyday Victorian life which needed to change or be completely eradicated. Though seemingly horrific at first glance, the act of looking back at the Victorian era can actually be hopeful, as it really does illustrate how far humanity has progressed in the realms of public health, medicine, and psychiatry.

Sources:

Douglas, Laurelyn. “Health and Hygiene in the Nineteenth Century.” The Victorian Web, 11 Oct. 2002, https://www.victorianweb.org/science/health/health10.html.

Picard, Liza. “Health and Hygiene in the 19th Century.” British Library, 14 Oct. 2009, https://www.bl.uk/victorian-britain/articles/health-and-hygiene-in-the-1...

“10 Dangerous Things in Victorian/Edwardian Homes.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-25259505.

Marsh, Jan. Health & Medicine in the 19th Century, Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 2RL. Telephone +44 (0)20 7942 2000. Email [email protected], 8 Dec. 2014, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/health-and-medicine-in-the-19th-...

“The 1848 Public Health Act - UK Parliament.” UK Parliament, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/town...