Created by Lissa Silk on Sun, 02/28/2021 - 14:45

Description:

Violence has changed in literature for children. Whereas didactic texts of the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries scare children, entertaining texts of the mid-to-late 19 century and beyond undercut violence and mock it. Early didactic texts were designed to reflect the ideals of the “child of sin.” This was the notion that all children were inherently sinful, and the only way to dispel this sinful child was to scare children into obedience by showing violence towards wicked or wayward children in the books given to them like Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) and The Fairchild Family (1818). In 1865, however, the notion of the “child of sin” was twisted with the publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. Alice revolutionized the stereotypical children’s book by mocking violence towards the residents of Wonderland through the Queen of Hearts. The early 20th century in Cautionary Tales for Children (1907) is when we really see a dramatic shift in children's literature as violence changes from being used to teach lessons to be mocked as a source of satire.

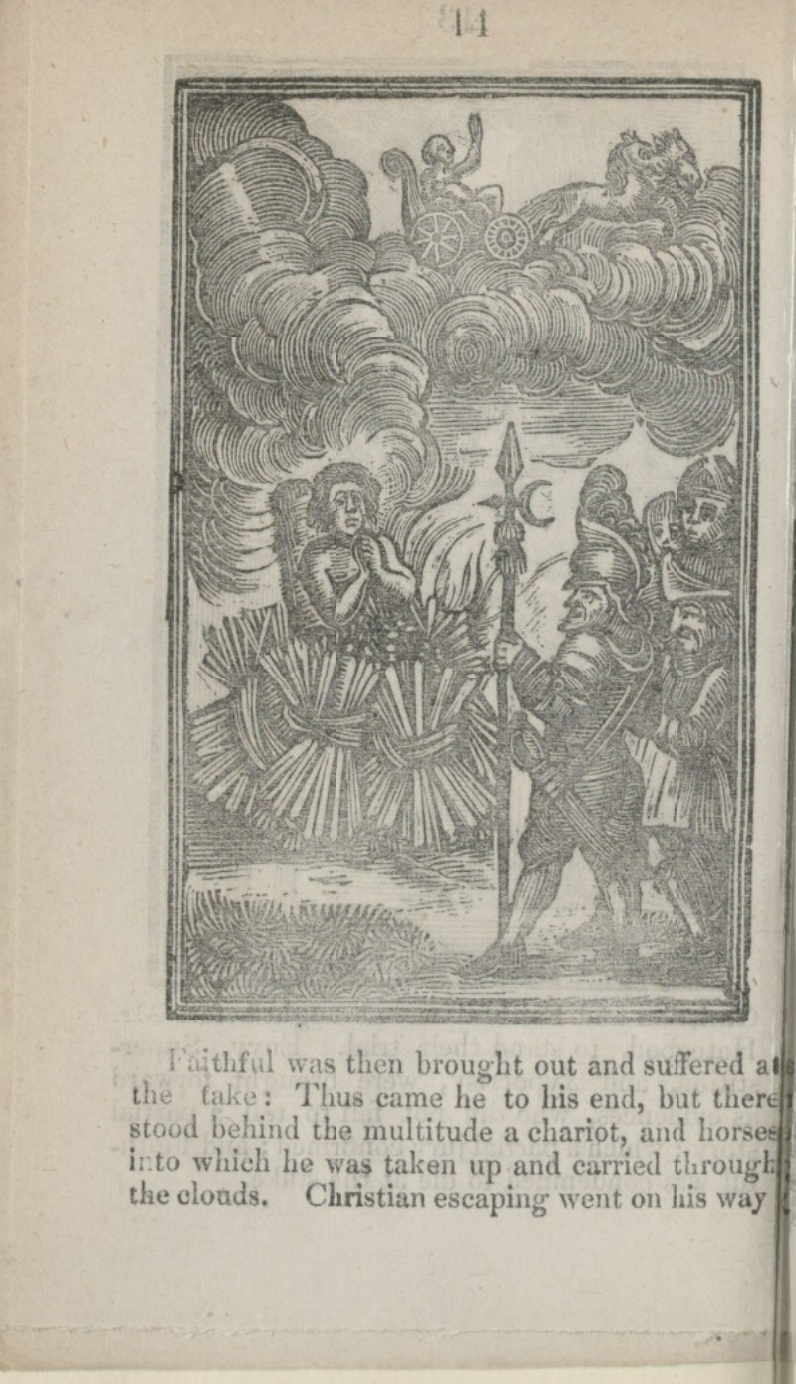

Plate from Pilgrim’s Progress: From This World to That Which Is to Come (1678, 1684), by John Bunyan, 1840 Chapbook edition, National Library of Scotland.

This first plate in the case illustrates the character Faithful as he cries and burns at the stake. Faithful is also shown clasping his hands and praying to God to get into heaven, which he is ultimately sent to. The message to be received from this image is that faith will bring you to the golden gates of heaven, but you have to be willing to die for it. This image demonstrates the violence that was commonly shown to children in the 1600s into the 1900s. As parents believed children to be inherently sinful, violence was commonly used to “scare the sin” out of children. This instance, however, showcases the character of Faithful getting burned for not committing a sin, and, thus, he goes to heaven. The violence in this image is not lost on the children that read it even today. As impressionable as children are, they mus have been in constant fear for their lives after reading this book. Whether or not they committed sin, violence might come upon them. The best way for them to ultimately be sent to heaven was to not question anything and adhere to the Bible.

Text from The History of the Fairchild Family (1818), by Martha Mary Sherwood, 1854 edition. This second plate is from The History of the Fairchild Family from the chapter entitled “Story on the Sixth Commandment.” Although it isn’t a picture of violence, the imagery of the text is arguably more gruesome than that of an image. In this scene, Mr. Fairchild shows his children, who have previously sinned in the story, the dead, hanged body of someone who committed a similar sin. Mr. Fairchild would not let the children leave the body until they confessed their sins and heeded the warning of not becoming like the hanged man. This instance of inherent violence and gruesome imagery is shown not only to the children in the book but to the children reading the book. The message to be taken away from this text is to adhere to the sixth commandment. At the time, the primary teaching method that parents and instructors knew was violence, and thus, it is reflected in the books they read.

John Tenniel, “Queen of Hearts Pointing at Alice,” for “The Queen's Croquet Ground,” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll.

This third plate is from the landmark text of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It shows the “villain” of the text, the Queen of Hearts, as she dramatically points to Alice, the heroine, and orders for her beheading. In mainstream didactic texts, this beheading would actually take place, and the moral to be taken from the book would be to not to model curious and inquisitive Alice. Carroll, however, turns this message on its head and puts Alice in a courtroom to have a trial against her accuser. This trial ultimately brings Alice out of her dream world of Wonderland unharmed. The dramatic shift from violence as a means of didactic learning to a means of entertaining satire began with the publication of this book. The blatant refusal to act upon violence in Carroll’s book is a significant shift in children’s literature at the time. Carroll mocks the use of violence as learning in his depiction of the Queen of Hearts being "crazy" and never truly acting on her promise of beheading. Instead, Carroll shows Alice learning through her own set of deduction skills.

Basil T. Blackwood, “Franklin Hyde,” in Cautionary Tales for Children (1907), by Hilaire Belloc.

This fourth and final plate highlights the 20th-century shift from violence as a means of learning to violence as a means of entertainment. This image depicts Franklin Hyde’s uncle as he kicks Franklin Hyde for being physically dirty. Clearly, this image is supposed to be humorous as the text along with it discusses how children shouldn’t play with dirt, mud, or slime, but they are allowed to play in the sand all they want. The obscure message of the poem mixed with the unrelatable characters of Franklin Hyde and his uncle clearly imply that the punishments shown in Cautionary Tales for Children are purely satirical. With the publication of this book, violence to punish children for their wrongs is completely thrown out of the mainstream and replaced with entertaining texts that depict violence as a means of comedic, satirical entertainment.