Created by Michaela Bauer on Tue, 05/23/2023 - 03:03

Description:

While it is tempting to believe that editions of books were always just mass produced in a factory ever since books were first invented, editions of books have their own unique qualities and there is no example more perfect than that of the 1909 edition of The Rubaiyat.

Since this edition was made in England during the year 1909, it was made during the Edwardian time period, which was a time period in which gift books were immensely popular. The most popular kind of books to give were editions of fairy tales and Christmas books that were often given to children (and Edmund Dulac’s (the illustrator of this specific edition of The Rubaiyat) sons had their own editions of Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales as giftbooks).

Hodder & Stoughton, the company that published this edition of The Rubaiyat, was founded in 1868 by Matthew Henry Hodder and Thomas Wilberforce Stoughton on on Paternoster Row, London. In the early twentieth century, Hodder & Stoughton published several classic authors including (but not limited to) J.M. Barrie and G.K. Chesterton.

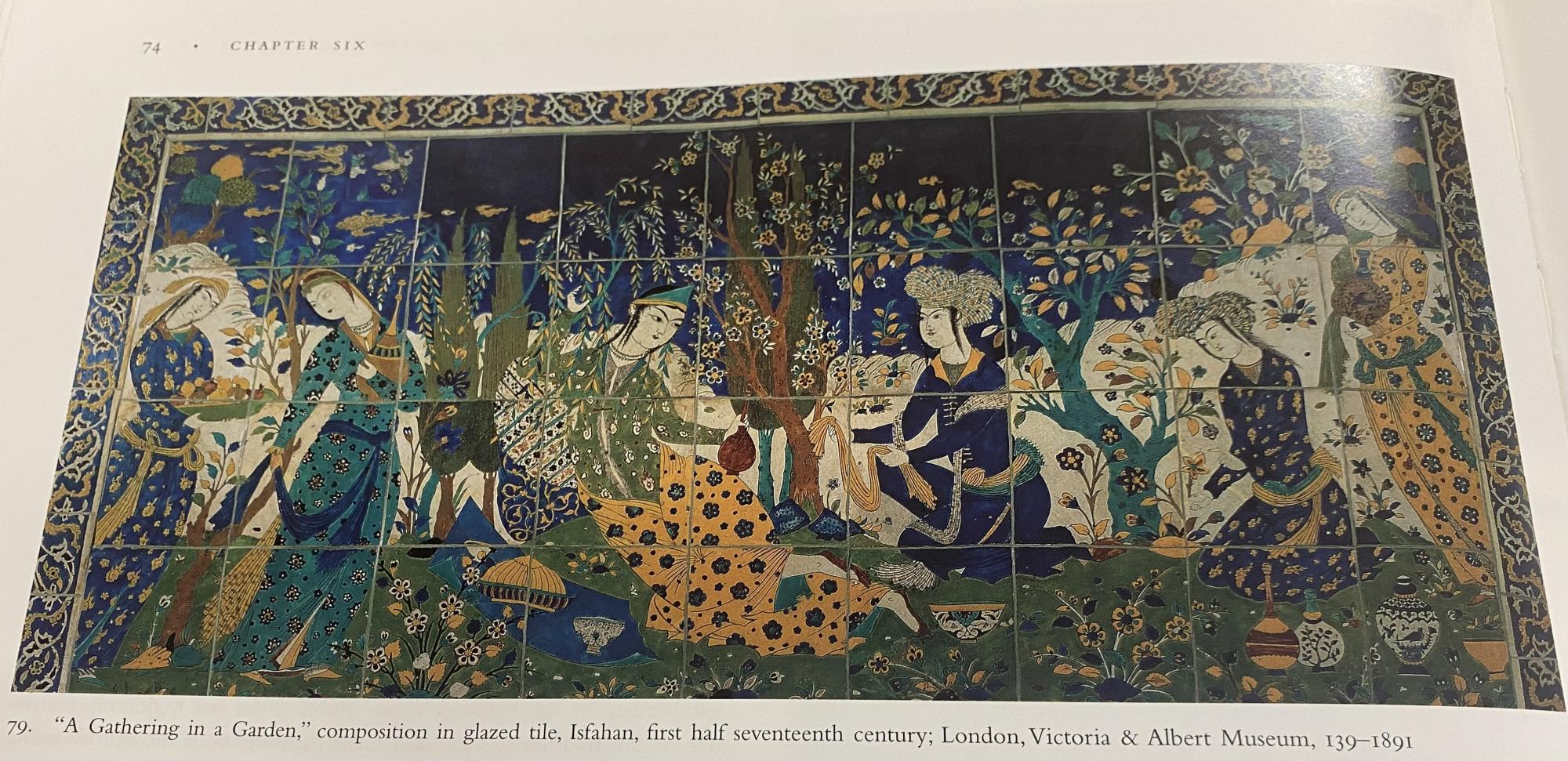

Isfahan became the new capital of Iran between 1597 and 1598 after Shah ‘Abbas I moved the Safavid government there in an attempt to revive the country from an economic depression. Shah ‘Abbas was a patron of book publishing and painting and, therefore, Isfahan became the capital for artwork during this time and the paintings of Isfahan became what people think of when they think of Eastern artwork to this day.

Since Dulac was heavily involved in the aesthetic movement, he likely drew inspiration for this edition from Isfahan artists of the seventeenth century (and these artworks of oil on canvas (see FIGURE 1) and glazed tile (see FIGURE 2) later became the overall standard for the western interpretation of eastern artwork (and this was the sort of artwork that one could find in editions of One Thousand and One Nights tales of Arabia). During the time period from 1890 to 1930, it was more common for British artists to use more muted colors rather than the more vibrant tones of the seventeenth century Isfahan artists and, while the illustrations of the 1909 edition of The Rubaiyat drew inspiration from the seventeenth century Isfahan artists, Dulac’s illustrations definitely have a more muted color palette).

During this time, it was also common for companies to “improve” the quality of their editions and one way that they did so was by the use of religious flavor. Since The Rubaiyat is an Islamic text rather than a Christian one, we do not see any such Christian religious overtones (although you could argue that Dulac’s illustration of Death (see FIGURE 3) can be interpreted as Christian as the personification of Death resembles that of the Christian take on Death).

The whole gift book trend during Edwardian times was problematic as it often resulted in publishing companies producing cheaply made gift books (in a way that is similar to fast fashion today where people want a particular clothing trend and often settle for cheaply and unethically made clothes). All of this information is yet another reason why the Victorian and Edwardian trend of Orientalism was a huge issue.

SOURCES:

Felmingham, Michael. The Illustrated Gift Book 1880-1930 With a Checklist of 2500 Titles. Gower Publishing Company Limited. 1988.

Hodder & Stoughton. Hodder & Stoughton. Hodder & Stoughton. 2019. https://www.hodder.co.uk/

Sardar, Marika. Shah 'Abbas and the Arts of Isfahan. Heillbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Met. October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/