The Novel In Context: Timeline

Created by Sara Danger on Wed, 02/10/2021 - 15:40

Part of Group:

The Novel in Context: Timeline

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa. 8 |

Origins: EpicAn epic "is a long verse narrative on a serious subject, told in a formal and elevated style, and centered on a heroic or quasi-divine figure on whose actions depends the fate of a tribe, a nation, or (in the instance of John Milton's Paradise Lost) the human race." (Abrams, Glossary of Literary Terms, 7th ed., p.76) *The hero is a of great national or even cosmic importance. *The setting is ample in scale, and may be worldwide, or even larger. *The plot entails superhuman deeds in battle, *typically written in a grand, idealized style. |

Sara Danger | ||

| circa. 1300 |

Origins: Prose Romance*Originated in the chivalric romance of the middle ages (from which "roman," the european term for the novel, stems) *features villians and heroes *the main character is often solitary and isolated from the social context; often set in the historical past Abrams, Glossary of Literary Terms: "The romance is distinguished from the epic in that it does not represent a heroic age of tribal wars, but a courtly and chivalric age, often one of highly developed manners and civility. Its standard plot is that of a quest undertaken by a single knight in order to gain a lady's favor; frequently its central interest is courtly love, together with tournaments fought and dragons and monsters slain for the damsel's sake; it stresses the chivalric ideals of courage, loyalty, honor, mercifulness to an opponent, and elaborate manners; and it delights in wonders and marvels." (7th ed, p. 35) *emphasizes adventure in quest for ideal and/or pursuit of an enemy |

Sara Danger | ||

| circa. 1500 |

Origins: The PicaresqueFocuses on a rascal, who lives by his wits (reaction to idealized, romantic plots/characters) *characters virtually unchanged throughout adventures *episodic in structure |

Sara Danger | ||

| circa. 1700 |

The Rise of the Novel: Watt in ContextWhy does the British novel “rise” in the eighteenth century? For Ian Watt: the rise of literacy, rise of capitalism, and development of philosophy and science focused on the autonomy and primacy of individual knowledge and perception (Locke, Decartes) as the source of knowledge, experience (e.g., the modern self). For M.M. Bakhtin: “After the Renaissance, the present (that is, a reality that was contemporaneous) for the first time began to make sense itself not only as an incomplete continuation of the past, but as something like a new and heroic beginning.” (The Dialogic Imagination 40) For Cathy Davidson: the increase in woman’s leisure time, literacy, and lack of formal education played crucial roles in the production and consumption of eighteenth-century novels. |

Sara Danger | ||

| circa. 1701 |

Ian Watt, Rise of the Novel, Main ArgumentWhy did the novel rise in the 18th Century? Watt's thesis: Developing concurrently with a new emphasis on individual knowledge and perception (e.g., Locke, Decartes) as the source of knowledge and experience (e.g., the modern self), the 18th century novel, according to Watt, “purports to be an authentic account of the actual experiences of individuals” as they live out their lives in realistic settings (The Rise of the Novel 27). Cathy Davidson helpfully sums up Watt's accounts of what comprises this shift; for Watt, the realism of novels “operates on numerous levels: linguistic (characters sound as if they are talking to one another); situational (. . .within the time and space of fiction); and personal (characters are viewed as individuals not types” (Davidson 52) |

Sara Danger | ||

| 1720 to 1720 |

Ian Watt and Moll Flanders"The ‘realism’ of the novels of Defoe, Richardson and Fielding is closely associated with the fact that Moll Flanders is a thief, Pamela a hypocrite, and Tom Jones a fornicator. This use of ‘realism’, however, has the grave defect of obscuring what is probably the most original feature of the novel form. If the novel were realistic merely because it saw life from the seamy side, it would only be an inverted romance; but in fact it surely attempts to portray all the varieties of human experience, and not merely those suited to one particular literary perspective: the novel’s realism does not reside in the kind of life it presents, but in the way it presents it." (ital. mine, 2) |

Sara Danger | ||

| 1720 to 1720 |

Ian Watt and Moll Flanders"Defoe and Richardson are the first great writers in our literature who did not take their plots from mythology, history, legend or previous literature. In this they differ from Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton, for instance, who, like the writers of Greece and Rome, habitually used traditional plots;" (3) Watt argues that new philosophies (by Decartes and Locke), which argued that particular individual perception and experience shape what and how individuals know themselves and the world. This, in turn, opens up new avenues for storytelling. Thus, according to Watt, "the actors in the plot and the scene of their actions had to be placed in a new literary perspective: the plot had to be acted out by particular people in particular circumstances, rather than, as had been common in the past, by general human types against a background primarily determined by the appropriate literary convention. This literary change was analogous to the rejection of universals and the emphasis on particulars which characterises philosophic realism. Aristotle might have agreed with Locke’s primary assumption, that it was the senses which ‘at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the empty cabinet’ of the mind. [5] Testing out Watt's theories: |

Sara Danger | ||

| 1722 to 1722 |

Formal Realism and the Novel: Watt's outline of featuresWhereas earlier periods had turned to universal, classical, traditional plots, which were retold and revamped by the artist, in the 18th-century, Defoe and others eshewed the traditional and classical and instead situated their plots within the everyday, oridinary lives of invididuals. Thus, "before the novel could embody the individual apprehension of reality as freely as the method of Descartes and Locke allowed their thought to spring from the immediate facts of consciousness, . . . the plot and the scene of their actions had to be placed in a new literary perspective: the plot had to be acted out by particular people in particular circumstances, rather than, as had been common in the past, by general human types against a background primarily determined by the appropriate literary convention." (Watt 15) Characterization (p. 18-19): Importance of particular names, realistic thought processes, represented as "particular individuals in their contemporary environment" (19), Setting: As opposed to timeless settings of classical art, the novel sets characters against "a background of a particularised time and place." "At his best, [Defoe] convinces us completely that his narrative is occurring at a particular place and at a particular time, and our memory of his novels consists largely of these vividly realised moments in the lives of his characters, moments which are loosely strung together to form a convincing biographical perspective. We have a sense of personal identity subsisting through duration and yet being changed by the flow of experience."(21 Place: "the pursuit of verisimilitude led Defoe, Richardson and Fielding to initiate that power of ‘putting man wholly into his physical setting’ [36] which constitutes for Allen Tate the distinctive capacity of the novel form; and the considerable extent to which they succeeded is not the least of the factors which differentiate them from previous writers of fiction and which explain their importance in the tradition of the new form." (Watt 27) Linguistic: Whereas "previous stylistic tradition for fiction was not primarily concerned with the correspondence of words to things, but rather with the extrinsic beauties which could be bestowed upon description and action by the use of rhetoric, "(28) the novel sought first and foremost language that gave an "air of complete authenticity" to the realism of the scenes, characters, and events; they are depicted with "closeness and immediacy" ( 27). The goal of the 18th-century novelist was to employ language that would " bring his [or her] object home to us in all its concrete particularity, whatever the cost in repetition or parenthesis or verbosity" (29) |

Sara Danger | ||

| The start of the month Spring 1789 |

"Ethelinde" by Charlotte SmithThe novel Ethelinde (1789), by Charlotte Smith is one of the first novels to be considered to include elements of the Gothic genre. Though Smith was known throughout her career for poetry, she began writing novels later in life in order to make money for herself and her family. She, much like Susannah Gunning, had much strife with her family and economic stability, which served as inspiration for her writing of Ethelinde. An article by Lisa Ottum about Smith’s work suggests that the setting in which she places her novels allude to a gothic style: “[i]n her fiction, Smith invests topography with a sense of depth that challenges other Romantic representations of nature, especially those that celebrate the panoramic view and its putative comprehensiveness,” (250). Smith centers Ethelinde in an abbey much like Austen and Gunning. In her illustration of the abbey as setting, she insinuates a mysterious melancholy that contributes to a romantically gothic style. This novel exemplifies the genre of abbey fiction, while also illustrating the overlap of gothic genre and the romantic period. Ottum, Lisa. “‘Shallow’ Estates and the ‘Deep’ Wild: The Landscapes of Charlotte Smith's Fiction.” Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, vol. 34, no. 2, 2015, pp. 249–272. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44784589. Accessed 4 Apr. 2021. |

Isabella Dempsey | ||

| circa. 1808 |

An Examination of Racism and Gender in "The Woman of Colour: A Tale"Olivia’s interactions with men vs. her interactions with women vary throughout the novel. However, when interacting with members of English society, she is consistently berated and/or put down.

This is most evident in her interactions with Mrs. Merton, which highlight the difference between women of colour and white women in English society. Much of waht the audience witnesses is Mrs. Mertons inherent need to compete with Olivia because she has been told throughout her life that she is "better" than women of colour. However, the reader gets to witness how Olivia is both much smarter and much more beautiful than Mrs. Merton, which is what attracts men like Mr. Honeywood. This exacerbates an interaction that is already rife with animosity between the two women because instead of partnering against the men, who regard both women with some distaste, Mrs. Merton constantly tries to put Olivia down. Through these examples, it is evident that racism pitted women against each other and further divided families during this period in English society.

For example: “A servant now interested with a large plate of boiled rice. Mrs. Merton half raised her head, saying--‘Set it there,’ pointing towards the part of the table where I sat. ‘What is this?’ asked Mr. Merton. ‘Oh, I thought that Miss Fairfield--I understood that people of your--I thought that you almost lived upon rice,’ said Mrs. Merton, ‘and so I ordered some to be got,--for my own part, I never tasted it in my life, I believe!’” (77).

“Mrs. Merton’s remarks on the gravity and the absence of Augustus, are made in my hearing, and in order to mortify and to wound me; but no remarks of hers can now have the power to add to the poignancy of my feelings” (91).

Interactions like this highlight how racism has taken over logic in English society. Instead of warning Olivia that Augustus is not what he seems, Mrs. Merton insults Olivia instead and revels in her emotional turmoil.

The betrayal of Augustus is also a telling moment for the reader to understand how racism and gender relate in English society at this time. Augustus revelas that he does not care about Olivia, and emotionally manipulates her throughout their relationship. He also lies to both himself and his friends about the situation. She is willing to call off their marriage when they first meet and pursues him to do so, but he manipulates her into thinking that he is in love with her. This causes Olivia to constantly second guess herself. Overall, his manipulation highlights how he sees people of colour as less than human. His disregard for her emotions is telling that men automatically saw women as lesser than them, but women of colour were treated especially heinously. Even Olivia's wit is not enough to help her against an apathetic man who does not care for anyone but himself. At one point Augustus states, “Are you so insensible to your own numerous and unrivalled virtues and perfections? Heaven is my witness, that I am warmly, sincerely interested for your happiness!” (93).

|

Gwyneth Hoeksema | ||

| circa. 1808 to circa. 1808 |

Racism and Social Class Structure in The Woman of Colour

|

Brianna Powell | ||

| circa. 1808 |

Said's Problem of Representation in The Women of Color“The capacity to represent, portray, characterize, and depict is not easily available to just any member of just any society; moreover the ‘what’ and ‘how’ in the representation of ‘things’ while allowing for considerable individual freedom, are circumscribed and socially regulated” (Said p80). This means that the concept of how things in the novel are represented is a means to keep the subordinate from rising. For example, Mrs. Merton doesn't shake Olivia's hand when they meet, makes assumptions about the food she eats, and constantly comments about the color of Olivia's skin to remind Olivia that she is still an outcast. Augustus does the same when he lets Olivia fall in love with him. Augustus already has a wife and is going after Olivia's money and he lies to her to get what he wants. All of these events are meant to limit and control the amount of respect Olivia receives as well as undermine her abilities. The harsh representation could also be the reason why the author of this novel chose to remain anonymous because the idea of representation is actually used to exploit all the mistreatment. This concept emphasizes the book's genre of realistic historical fiction. |

Johanna Schulz | ||

| circa. 1808 |

The Woman of Colour and Said: The Impact of ImperialismWhen looking at the impact that Western imperialism had on cultures, one word comes to mind: all-encompassing. Throughout history, we can see this idea of western expansion or journeys into "unoccupied" territories and these often come at the cost of dehumanizing those that are being overtaken by this expansion. Said points this out within his article when he states: “But positive ideas of this sort do more than validate “our” world. They also tend to devalue other worlds and, perhaps more significantly from a more retrospective point of view, they do not prevent or inhibit or give resistance to horrendously unattractive imperialist practices” (Said 81). For those who believed in these Western ideas pertaining to expansion and superiority, beliefs that other people could have a culture or a life that matched the importance of their own (white) one was impossible. Seeing these ideas of imperialist effects through a first-hand perspective provides an interesting view into how widespread these beliefs are. For Olivia, she is immediately introduced to this belief. When meeting Mrs. Merton for the first time, she states "I believe I held out my hand... but I fancy its colour disgusted her, for she recoiled a few paces with a blended curtesy and shrug, and simpering, threw herself on a sofa" (71-72). For Mr. Merton, there was no hesitation to approach and embrace Olivia. There is a multitude of reasons that Mrs. Merton could hold this belief against Olivia. Said's argument helps the reader contextualize reasons that Mrs. Merton may have acted like this. |

Jessica Creech | ||

| circa. 1808 |

Said's Understanding of How Imperialism Changes Culture“Hobson described imperialism as the expansion of nationality, implying that the process was understandable mainly by considering expansion as the more important of the two terms, since “nationality” was a fully formed, fixed quantity” (Said p83). This means that if you came from a country without imperialistic views, you were an outcast and of a different nationality. This is not something you can hide or debate because you can't change your nationality. Olivia went to England with a new-found honor after the British slave trade was abolished. In the text, Olivia explains how imperialism changed how people outside of England were viewed through her conversation with little George. On page 80 in The Women of Color, Olivia points out the difference of the words “slave” and “servant” to him. A "servant" refers to a slave and comes from the perspective of anyone who owns a slave. This word is meant to sound as a cover-up of the mistreatment slaves underwent. The term "slave" exploits the truth and experiences of how terrible slavery was. The Merton family uses the word "servant" while Olivia uses the word "salve". Olivia’s time in England was very different from her life in Jamaica when she went back. On page 156, Olivia remembers her wish for peace and comfort that she hoped to find in her marriage with Augustus as she is getting ready to leave England. She said she loved him too much and it caused her to lose sight of her goals. As a result, she lives a quiet life and enjoys things like her work in the garden and reading her books while staying away from society. She feels comfort with the people she is surrounded with. This distinction between the two countries is crucial to understand Said's point of view of how imperialism changes culture. England is a place where culture was not celebrated and resulted in Olivia's mistreatment. Olivia felt the most at peace at her home in Jamaica because her culture was celebrated there. |

Johanna Schulz | ||

| circa. 1810 |

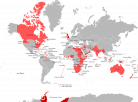

The Woman of Colour and Said: Widespread ImperialismIt is no secret that imperialistic ideas swept through the United Kingdom. Soon, these ideas were spread throughout the world as the U.K. expanded towards what is now the U.S., Canada, the eastern coast of Africa, Australia, and more (see map). When thinking of this time period, it is easy to get lost in the politics of it all but Said points out just how much support these Western beliefs had. Said states “We can sense how ideas about dependent races and territories were held both by foreign-office executives, colonial bureaucrats, and military strategists and by intelligent novel-readers by educating themselves in the fine points of moral evaluation, literary balance, and stylistic finish” (Said 95). It is important to note that while the political/expansion decisions were made by higher-ups in society, there was widespread support from across the country. Within The Woman of Colour, we can see Augustus commenting on these prejudices and imperialist beliefs. Augustus writes “Prejudices imbibed in the nursery are frequently attached to the being of ripened years” (80). Augustus points out that from birth, children are exposed to their parents' beliefs and if their parents strongly support an idea, they will too. |

Jessica Creech | ||

| circa. 1813 |

The Woman of Colour Discussion Questions

|

Jessica Creech | ||

| Winter 1832 to Summer 1833 |

Fall River

The major contribution of this essay is that it shows how the author, or in this case the editor, took a real place (Fall River) and added a little bit of fiction without taking the history out of the novel. The story is being enhanced instead of changed. Patricia Caldwell even put the real letters that S.M C wrote into the novel. This helps readers understand the reality of what had happened in Fall River which helps build a connection between reader and author. Additionally, Catherine Williams recreated an incident that has already happened in Fall River, therefore, readers can also get a sense of the historical context of this town.

The major contribution in this quote shows the status that women had, not only in society but even in novels. For instance, in Fall River many people blamed the pregnant woman for her own death and even said that she deserved it. We also see the inferiority of women in Moll Flanders when she believes that she needs a husband to strive. Even female characters are more prevalent, it seems as if something bad always happened to them in novels during this time. This mistreatment of females in novels can be shadowed by what is happening in society during this time. |

Mariah Sturdivant | ||

| 1833 |

Williams' America“What local issues were fictionalized, were considered significant enough to warrant the attention of the novelist and the reader?” (Davidson 68) Davidson argues that early novels “provided the citizens of the time...with literary versions of emerging definitions of America” (Davidson 67). Williams’ opinion often shows through her means of narration in Fall River, from the very beginning of the book in which she refers to Cornell as the “unfortunate heroine of the tale” (Williams 6). Wiliams describes in multiple instances the “recklessness displayed by the prisoner’s friends of the character and peace of individuals”; she is not shy in suggesting that there is an unfairness in the way the trial was handled, and the testimony that was accepted (55). Throughout the book, this narration implies a criticism of the religious communities in America at the time, and how loyalty to those communities negatively impacted Avery’s trial. Williams’ narration, in other words, is the lens through which she constructs her “vision of a developing new nation,” including the issues which plague it (Davidson 68). Image citation: Mazzola, Francesco. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. 1523, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. |

Jillian Downs | ||

| 1833 |

Context of the Reader“My problem, of course, is that my readers have been dead for almost two hundred years, so one can hardly interview them to reconstruct an early American interpretive community.” (Davidson 62) In her essay, Davidson speculates on the role of the reader in the historical context a book was written in. “It is simply too easy to perpetuate assumptions about the reader that neglect the inescapable fact that readers, as much as texts, operate within historical contexts,” she writes (Davidson 61). Our readings of Fall River come from a modern perspective where the role of Avery as a preacher is not so drastically consequential; we have heard tales like this before (many of us may have read The Scarlet Letter, for instance.) This complicates our current reading, as it removes some of the shock and social complication, and it removes the implications made when Cornell’s character is questioned during the trial. (In my reading, questioning the character of the victim seemed completely unreasonable, but evidently this would have held enough merit at the time to be permitted.) Image citation: Mount, William Sidney. The Herald in the Country. 1853. |

Jillian Downs | ||

| circa. 1834 |

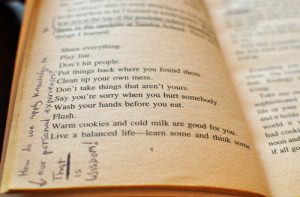

Davidson on Marginalia and Authors as Readers

“I suggest strategies by which texts may be deciphered in terms of the complex set of generic, stylistic, thematic, cultural, ideological, and literary expectations that readers bring to texts and that authors (themselves readers of the work that they are writing) play with and around in the creation of texts” (Davidson 60). “In extant copies of the novels and in other kinds of books as well, readers have often left their marks . Inscriptions and marginalia tell us something about how books were valued and how they were read” (Davidson 62). Davidson’s argument about the usefulness of a reader’s marginalia can be connected to the impact of Williams’s footnotes throughout Fall River. Because authors are “themselves readers of the work they are writing,” Williams’s footnotes provide insight into the thoughts and cultural influences that went into her writing. Examples from Fall River“Who can wonder that infidels should be strengthened by such things as these? What a farce does even Christian worship appear when prostituted to secular purposes” (Williams 40). “What mighty despotism, what scheme of bondage, what film of ignorance and fanaticism, what system of ecclesiastical tyranny, may not the death of this woman be intended to break?” (Williams 45). These footnotes are examples of moments in the text where Williams felt compelled to break from the narrative to insert her own thoughts about the story. These annotations on her own story provide us with useful information about the beliefs and emotions that influenced the author in her writing. Image Citation:

Burnell, Carol, et al. “Annotate and Take Notes.” The Word on College Reading and Writing, Open Oregon Educational Resources, openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/chapter/annotate-and-take-notes/.

|

Abby Palmer | ||

| circa. 1834 |

Religious Communities in Fall River

“Although religion remained a potent force in many individual lives, the structure of religious authority changed demonstrably with revivalism; with the emergence of new denominations, sects, and even religious cults” (Davidson 71). “‘No,’ he answered, ‘she was not a leading member there, that she had been set aside for impudence, and imprudence of conduct,’ or something like that, when the fact was that this same woman had been considered as a leading member in that society for more than twenty years, that she had been of great service in the cause of methodism in Providence particularly, and it is believed by many has done more towards building up the Methodist society in that town than any three persons who could be named” (Williams 47). Connecting Davidson’s point about the changing structure in religious communities to the novel, it is clear that Williams was heavily influenced by this cultural context while writing Fall River. Not only is this religious shift seen in the plot of the story, but it is also seen influencing Williams and her view of religious authorities (especially in the Methodist community). Image Citation:

“‘Fishing with a Large Net’: United Methodist Camp Meetings.” The United Methodist Church, 3 June 2019, www.umc.org/en/content/fishing-with-a-large-net-united-methodist-camp-me...

|

Abby Palmer | ||

| 1834 |

DiscussionIf we are not the intended readers of Fall River, who was? What readers do we expect of different books today? What genre would you consider this novel to be? What elements of the novel helps support your claim? After reading Moll Flanders and Fall River, how do the female characters differ? How are they similar? |

Jillian Downs | ||

| 1854 |

Altick & Dickens in Conversation (Bianca)

In Altick’s article, he mentions how books were not as accessible as they are today. However, there were books that were considered “Yellow-back”/Railway novels so those who couldn’t afford to buy a novel could still read. Altick states that it wasn’t just the poor people that would read them but “it was said, in fact, that people went to railway stations for the books they were ashamed to seek at respectable shops” ( 301). This demonstrates that even those who could afford books may have also gone out to read these types of novels because of the stigma there might be about them at shops. Altick brings this point about because it demonstrates the positive part about having books accessible to others. Altick writes, “No longer was it possible for people to avoid reading matter” (301). This goes to show that the opportunity to read was starting to become more accessible and if people wanted to read they had the opportunity to do so. This can be tied back to the main theme of creativity and curiosity in Hard Times by Dickens because when Mr.Gradgrind catches Louisa and Tom looking at the circus, he is furious and wants them to have nothing to do with it. He even goes on to say, “Thomas, though I have the fact before me, I find it difficult to believe that you, with your education and resources, should have brought your sister to a scene like this” (Book I, Chapter III). Mr. Gradgrind exemplifies how others would have reacted if they see someone of a higher class reading a “Yellow-back” novel. However, Louisa and Tom exemplify how if someone wants to enact on their creative side, they are going to find a way to do so, just like those who found a way read even if it was through “Yellow-back” novels. In both instances, it shows how if someone is wanting to do something whether it is reading or going “against” their education and being creativity and curious, they will find a way to do so. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1854 |

Altick & Dickens in Conversation (Bianca)

One of John Cassell’s books Popular Educator helped many individuals become educator. For instance, Altick writes, “Thomas Hardy taught himself German from the Popular Educator; Thomas Burt, the labor politician, used it for English, French and Latin lessons; and with its aid the future great philologist, Joseph Wright, atoned for his almost complete lack of formal education. ‘The completed book,’ said Wright, ‘remained my constant companion for years. I learned an enormous lot from it’ ” (303). By giving examples as to how a book can help educate an individual it is easy to also notice how this form of education mainly served those of higher class. The idea of education and class is also seen in Hard Times specifically looking at Stephen and Bounderby, The reader can notice how they are both from different classes and have a different from of education mainly by looking their dialogue and dialect. In the scene where Bounderby is firing Stephen Dickens writes, “ ‘You can finish off what you’re at,’ said Mr. Bounderby, with a meaning nod, ‘and then go elsewhere.’ ‘Sir, yo know weel,’ said Stephen expressively, ‘that if I canna get work wi’ yo, I canna get it elsewheer.’ (Book II Chapter V). Through Stephen’s dialect and dialogue, the reader can notice that Stephen doesn’t speak like Bounderby, and he is of a lower class than Bounderby. However, in Altick’s article there seems to be the idea that if Stephen would have had his hand on books (if accessible to him), Stephen would have been able to self educate himself as to how to speak properly. This just demonstrates how the higher class did have it’s advantages specifically in books because books were the one that assisted them in becoming more educated throughout the time. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1854 |

Discussion Questions

|

Rose Chervinko | ||

| circa. 1854 |

The Book Trade- Altick's Main Ideas (Rebecca)Altick begins his description of the expanding book trade by highlighting the greed of publishers. In the early 1850s, publishing houses wished to maintain high book prices in order to maximize their own personal revenue. Because of this, individual consumers were unable to purchase “new publications” or original editions, taking away their individual buying ability entirely. In 1854, a writer for the Times articulated the public dismay at the purchasing system in place, saying, “We simply ask, on behalf of all classes, but especially in the interest of the great masses of the people, that the old and vicious method of proceeding shall be reversed” (Altick 291). Unfortunately, the publishers were hesitant to budge at the expense of their own profits. As the 1850s continued, individuals in the working and lower classes then found themselves gravitating towards libraries and book clubs, environments in which reprints could be exchanged and their desire for novels could be fulfilled at a cheaper price. Libraries then became businesses of their own, exchanging subscription fees for access to reprints. These libraries soon became the sole, direct consumers of publishers, who provided a slight discount in order to promote selling original editions in bulk. This allowed libraries to gain access to novels which they could then turn around the peddle for their own profit, while publishers were able to maximize the total copies being sold. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1854 |

The Book Trade- Altick's Main Ideas (Rebecca)Books began to spread outside libraries as well, alongside the demand for reprints at lower prices. In 1855, “yellow-back” or railway novels became common occurrences in railroad stations. As train rides became longer, and their riders required entertainment, novels were provided to ensure their demands were met. W. H. Smith & Son was said to have monopolized this industry, establishing enticing book “concession stands” in almost every station across the country. These concession stands were said to draw in travelers with their illustrative advertisements and their varied reading materials, including books, newspapers, pamphlets, etc. Altick acknowledges the increased accessibility of books as a result of the development of book concession stands in saying, “No longer was it possible for people to avoid reading matter….” (301). Fiction was not all that was being circulated in the early 1850s. John Cassell became the first individual to begin circulating educational materials in the same way novels were dispersed: in cheaper, divided parts. His most famous work, Popular Educator, which was released in 1852 proved to be a detrimental piece of educational material for many recognizable individuals at the time. Furthermore, Cassell introduced the idea that lower classes could gain access to information and education in a more casual, and ultimately cheaper, way. Illustrated, informational texts soon began to emerge, including examples like The Bible and The History of England. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1854 |

Altick & Dickens in Conversation (Anne)

Altick describes the importance of accessibility in the eyes of the authors themselves. He writes, “Often it was the author, rather than the publisher, who had to take the initiative in getting out a cheap reprint. Only when John Stuart Mill, moved by frequent pleas from workingmen, offered to forego his half-share of the profits, did [his publisher] agree to issue a cheap People's Edition of his works” (298). Mill struggled to make his work accessible for all. Even though the new publications were sold to libraries, Mill proves that authors still wanted their novels to be owned by anyone. As a contemporary of Dickens, he must have had similar concerns. In Hard Times, Dickens explicitly mentions this issue of accessibility and the business of libraries. Gradgrind says, “There was a library in Coketown, to which general access was easy. Mr. Gradgrind greatly tormented his mind about what the people read in this library . . . It was a disheartening circumstance, but a melancholy fact, that even these readers persisted in wondering . . . about human nature, human passions, human hopes and fears, the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the cares and joys and sorrows, the lives and deaths of common men and women!” (Book I, Ch. VIII). Dickens refers to the business of libraries and Gradgrind’s system of a transactional education in the same passage to equate the concepts. Art, in this case books, has become a basic product to be bought and sold which takes out some of the “wonder.” The rise of the library business spawned by the greed of publishers touched authors like Dickens and Mill deeply. This image depicts Gradgrind trying to comfort Louisa the morning after she stands up James. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1854 |

Altick & Dickens in Conversation (Anne)Cheaper books allowed for more access to more classes of people. However, Altick mentions a contrast between certain bodies who read. One side fancied sensational literature whereas others preferred the “high culture” of classics or nonfiction. Altick writes, “The enduring popularity of literature of adventure and crime disheartened many who had welcomed the . . . dawn of an era of improved public taste. A more hopeful sign was the increased demand for cheap books of an altogether higher level “ (308). The comparison and presumed superiority of one over the other way of thinking is quite like the split between facts and imagination in Hard Times. Dickens makes the argument that life devoted solely to objectivity and facts will lead to misery. As her father calls fairytales and the like “destructive nonsense,” Louisa’s emotional development is greatly hindered (Book I, Ch. VII). She says, “In this strife I have almost repulsed and crushed my better angel into a demon. What I have learned has left me doubting, misbelieving, despising, regretting, what I have not learned; and my dismal resource has been to think that life would soon go by, and that nothing in it could be worth the pain and trouble of a contest” (Book II, Ch. XI). Once Louisa’s heart is awoken by James, she has no idea how to deal with these new feelings as she becomes “repulsed” and “crushed.” She was raised her whole life to look to facts and figures to solve problems, and those don’t apply to emotions. Whereas people like Gradgrind think some books are of a “higher level,” others would claim that too much exposure of one side is harmful. Dickens, through Louisa’s example, is arguing for a balance between sensational literature/imagination and high culture literature/facts. This image is Sissy and Louisa, presumably as children. |

Rose Chervinko | ||

| 1877 |

Nature in the Story of Avis(Alyssa M.)According to Bakhtin, one of the things that makes a novel (and separates it from an epic) is that the hero is showing growth. In a novel, “the hero should not be portrayed as an already completed and unchanging person but as one who is evolving and developing, a person who learns from life” (10). In The story of Avis, Avis’s internal struggles are often seen coinciding with nature. More specifically, Avis appears to be in nature every time she is having a moment of growth for her character. One example of this is in chapter 4 when Avis is hiding from her aunt and climbing trees to read. The text states “The illuminated hours of life are few; but those of our first youth have a piercing splendor which neither earlier nor later experience can by any chance absorb. Avis was, perhaps sixteen, when one of these phosphorescent hours flashed upon her… She was down in her father’s apple-orchard, where the low, outskirting branches yield the outlook to the sea. Between her and the shore swept placidly the expanse of the farm…” (53). It continues to expand on details before saying that “it seemed to be the first time that she [Avis] had ever really thought she was alive” (57). This is one of the first moments where the readers are able to see that Avis enjoys making her own choices that differ from the path others have in mind for her. It’s during this moment when she’s up in the tree and looking out across nature that Avis is really believing that she has the power to make these decisions for herself. Another example is in chapter 7, after Avis and Ostrander engage in an argument over the chance at a relationship. The text states “Avis stood as he had left her till he was out of sight; then slowly, as if each nerve and muscle in her body yielded separately, sank down among the daisies, throwing her arms above her head, among their roots. She was worn with the strain of the last few days. She thrust her cheek down into the cool, clean earth, and let the grass close over her young head with a dull wish that it were closing for the last time” (131). The importance of nature here in this scene is that Avis had just expressed her major concern with marriage: that “marriage is a profession to a woman and I have my work” (129). Avis dropping down to just lay amongst the daisies shows how much her internal struggle has been weighing on her. Similarly to the idea Bakhtin mentions that a hero in a novel must be changing, The Story of Avis presents the heroine’s “growth moments” (including moments of realization, struggles, etc.) to be with nature. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1877 |

Avis is Contemporary and Progressive(Alyssa T.)Bakhtin highlights three characteristics that he believes constitutes the unique genre of the novel. One of these says that, “From the very beginning the novel was structured not in the distanced image of the absolute past but in the zone of direct contact with inconclusive present-day reality. At its core lay personal experience and free creative imagination” (38). I believe that Avis’ character is a perfect example of this, since we follow her contemporary and progressive personal experience throughout the story. And specifically since it was written in the mid to late 19th century, her personal experiences we read about would have been very unconventional for the time. Even as a teenager, she pushed back on the expectation that women should take care of things around the house, when she told her father, “”Aunt Chloe says it’s unladylike to hate … if it is, then I’d rather not be a lady. There are other people in the world than ladies. And I hate to make my bed; and I hate, hate, to sew chemises and I hate, hate, hate to go cooking round the kitchen” (50). The fact that she was so sure of herself and what she believed in at a younger age is so telling of how contemporary her experience is. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1877 |

Avis Can be Inspirational to Other Women (Alyssa T.)To go along with Avis’ desire to break the traditional role of women, Bakhtin illustrates how readers can see themselves in characters of a novel, and this is another aspect of this genre that is so influential and special. He explains this, when he says, “We can experience these adventures, identify with these heroes; such novels almost become a substitute for our lives. Nothing of the sort is possible in the epic and other distanced genres” (32). Despite not wanting to engage in stereotypically womanly work, another thing at the core of Avis’ character is that she does not wish to marry. She explains this in detail, when she says, “I do not say, Heaven knows that I am better, or greater, or truer than other women, when I say it is quite right for other women to become wives, and not for me. I only say, if that is what a woman is made for, I am not like that: I am different. And God did it” (195). This, of course, goes against the expectation of women at that time, but if a woman reading it then, or even now, does not ever wish to marry, they would know that they are not alone. Not only that, but if they are religious like Avis seems to say she is here, they can also know that there is nothing inherently wrong with them because they do not want to get married. Even if a woman can not resonate with Avis’ lack of interest in marriage, she is also relatable in other ways. When Coy is looking at Avis’ portrait of Ostrander, she tells her, “‘I may say that the greater part of Harmouth is familiar with the history and progress of this portrait’’ (107). And Avis says, ‘Oh! I suppose so … It is just so if a woman writes a poem, or does any thing less to be expected than making One-Two-Three-Four Cake’” (107). I believe so many women can see themselves in Avis here, because if any of us dare to step out of the box of what a woman is expected to do or act like, we are constantly questioned or feel like we have to prove ourselves. So in all these ways, I believe Avis is very contemporary for her time, but was and still is a good character for women to either look up to, or see themselves in. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1877 |

Foreshadowing Through Epigraphs (Hailey H.)Amongst all the little quotes at the beginning of each chapter, all of them have one thing in common; they are all either poems or written by poets or someone in the artistic world from plenty of different time periods. They could mean a plethora of different things, since we will never know the author's true intent of those little excerpts, but I believe they are a sort of foreshadowing device or something similar. For example, chapter one's excerpt is about a bird flying above someone and they can only see the shadow of that bird, “And all I saw on the sunny ground, The flying shadow of an unseen bird” (7). Avis could be that bird, flying above everybody so high that they can only see her shadow. She may be unseen, but others can still see her shadow and follow her influence if you look hard enough, “Avis Dobell, sitting in the shadowed corner of the presidents parlor that night” (13). You have to look hard enough to find the true meaning in any work, real or not. If you just take one glance around the room, you’ll miss the true wonder in the shadows and you won’t get to explore the possibilities that lie within. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1877 |

Thematic Resonance Through Epigraphs (Hailey H.)Using another chapter as an example, chapter threes excerpt seems to be a little bit different. For one thing, there are two different quotes here, one by Plato and one by Goethe, but i want to focus on goethe. His quote is from his unfinished work Pandora, “Young, and a woman; ‘tis thus she was mine” (36). Goethe unfortunately never finished this work, but this quote still has meaning to the story of Avis in one way or another. Avis already stated that she would never marry, since her mother married her father and never got to act on stage in theater like she wanted, “‘ I married your papa: that is why I never acted in the theatre’” (44). Her mother never got to fulfill her dreams of theater because of marriage, so Avis sees marriage as something that will hinder her ability to complete her dreams. To Avis, dreams and passions are something to be completed and not put off for another day or for another lifestyle. She wants to complete her dreams and no one is going to stop her from doing that, even if she is going against societal norms of that time. You have to develop your own life and your own style, not follow one society has left for you. Life is always changing, so who can say what you’re meant to do but yourself. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1937 |

Humanity V. NatureA major theme present in the novel is humanity versus nature. As the title suggests, in the novel we see that no human desires, whether for money or love, can win against God or any forces of nature. |

Ashlyn Houser | ||

| 1937 |

Discussion QuestionsQ: As the novel progresses, we see Janie become more immersed in black culture. (From her childhood, Eatonville, and the Everglades) Early on, we learn that Janie did not know she was a black girl until the age of 6 due to being surrounded by white people her entire life. With the absence of her biological parents and the presence of Nanny, how do these experiences in her childhood shape the way her identity evolves as she becomes older? Q: In the novel, speech is used to show control. What are the major differences between the speech we see from the men in the novel versus Janie and other women characters? Are there any examples that come to mind? Q: How do you think the quote, “They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” and the journey of Janie’s independence are intertwined? Q: How important was the author’s use of southern dialect to your understanding of the text? Did it help you understand the community and their way of life? Did you find it unnecessary and distracting? Q: In the Perusall reading, we learned about Zora Hurston’s contribution to acceptance of Aftrican American’s in society. Where did you see this reflected in the novel? Are there specific scenes that you found noteworthy? |

Ashlyn Houser | ||

| 1937 |

Love, Marriage, and Independence in Their Eyes Were Watching God (Skye)Love and marriage were structured to be the peak in women's lives within society for ages, as fairytale endings, the expectations of motherhood, and female roles have been instilled. In Janie's story, this deems true as she puts love and happiness within the same regard, depicted in the statement, “There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the umated? Did marriage compel love, love the sun the day” (Hurston, 53). Janie's understanding of love changes as does her understanding of herself and her own identity in Their Eyes Were Watching God. Beginning the novel with an innocent, romantic, yet potentially inordinate value and need for love and marriage, Janie's own path to independence and her sense of self is informed by her experiences that stray from this initial expectation of love. Loneliness and a lack of that sense of powerful love that Janie envisioned within her marriages with Jody and Logan consumed Janie, making it complicated for her to find her own independent power. This is directly symbolized in Jody's treatment of Janie, as he is possessive and abusive. As a black woman especially, social expectation placed significant boundaries on Janie's autonomy to speak and be heard, thus affecting her view of herself and her happiness. Walker assesses this throughout her essays, especially in analyzing the representation of black women in texts and society. Walker writes "Black women are called, in the folklore that so aptly identifies one's status in society, 'the mule of the world,' because we have been handed the burdens that everyone else...refused to carry," (237). In this, Walker points out the image that black women are given in society, that in turn affects their image of self and their happiness. Walker continues to address the way in which black women's character is distorted, ignored, and disregarded in saying "When we asked for love, we have been given children...our labors of fidelity and love, have been knocked down our throats," (237). It is not until Janie realizes there is more to her life and her identity than love in her marriage with Tea Cake, where she finds her voice and her worth not as a wife, but as Janie. Though Janie's race is not as frequently addressed in this text as other novels we've read, these readings of Walker's work are still valuable as Zora and Janie, both, are both black women. |

Skyler Sherwood | ||

| 1937 |

Speech and Silence in Their Eyes Were Watching GodThroughout the novel, we consistently see Zora Neale Hurston use an unique style of language, specifically the rural Southern black dialect. Hurston depicts Janie’s life as a series of events which help her to acquire her own “voice,” which is the acknowledgment and expression of identity of the person she realizes herself to be. In the beginning of the novel, we learn about Janie as a very young, subservient, and most importantly a quiet girl. Throughout Janie's life and now in her marriage to Jody, she has served a subservient role: "No matter what Jody did, she said nothing" (76), and “she let it pass without talking” (78). Here Hurston is hinting at the fact that Janie's silence allows her husband to control her, restricting her from realizing her full potential. She states: “Maybe he ain’t nothing, but he is something in my mouth. He’s got tuh be else Ah ain’t got nothin’ to live for. Ah’ll lie an say he is. If Ah don’t, life won’t be nothin’ but uh store and uh house” (76). These thoughts represent the development of her identity as an individual, she is beginning to wonder who she is. By Janie stating that Jody is in her mouth she is suggesting that he is the one speaking, therefore he is her identity. It is this realization that allows Janie to begin examining her own identity and how she can express herself. Janie recognizes that she has to learn who she is and begin expressing that person until the end of her story.

A major aspect of Janie’s identity is the journey she went through to find herself. This aspect of discovering oneself is often how we leave our “mark” on the world. By passing down stories of struggle and success, following generations are able to see the process of establishing one’s identity and the process one takes to get there. In Alice Walker’s essay, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” she mentions how black women have consistently been silenced when trying to tell their own, individual stories. We have minimal literature and novels from the early 1900s that are taught and discussed that depict the struggles of black women. For this reason, it is incredibly important that Janie, and Hurston, were able to tell her story within Their Eyes Were Watching God. Walker states, “But this is not the end of the story, for all the young women - our mothers and grandmothers, ourselves - have not perished in the wilderness. And if we ask ourselves why, and search for and find the answer, we will know beyond all efforts to erase it from our minds, just exactly who, and of what, we black American women are” (Walker 235). Through generational storytelling, individuals, specifically women, are able to ensure that their stories are heard and continued, even after they have established themselves and passed on. The language and dialect present within the novel demonstrates the importance of passing stories down through generations to ensure their longevity and provide guidance for those who come after. |

Nichole Mitchell | ||

| 1941 |

Bakhtin on the Epic and The Novel (Kyle B.)Throughout Bakhtin’s essay, we see him distinguish the novel from the literature of its past. One of his main suggestions for the novel is that we cannot see it as a fully formed genre, given the fact that it has not died off. Since the novel is still a literary form that we still frequent, Bakhtin claims we cannot fully identify all of its features, as it is still evolving and experimenting and molding itself in different and varied ways. Bakhtin states, “The generic skeleton of the novel is still far from having hardened, and we cannot foresee all its plastic possibilities,” (Bakhtin 1). However, Bakhtin suggests that the epic is the inverse of this, as he states, “ We encounter the epic as a genre that has not only long since completed its development, but one that is already antiquated. With certain reservations we can say the same for the other major genres, even for tragedy,” (Bakhtin 1). Bakhtin suggests that the epic is one genre that has lived its entire lifespan and now can be analyzed for all its attributes. He suggests that the epic is focused on the past, and centers itself around the ideas of tradition. These diametrically opposed genres, while both very different, also provide a connection between the way that literature has evolved, and show us how the novel differs from its formal predecessors in genre. |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| Spring 1941 |

Discussion QuestionsWhat Themes were most resonant to you while reading The Story of Avis? What themes best connect to Bakhtin's essay? What themes within the novel complicate or problematize Bakhtin's arguments? Based on the annotations seen on Perusall, I noticed that many of us struggled with approaching Bakhtin's arguments. What were some of the problems in Bakhtin's argument? What parts of Bakhtin's argument did we agree with? How does The Story of Avis engage with the literature of its past? Does it take a particular stance on this past literature, or art? How does the author's use of descriptive language affect the story? Why does she choose to describe nature and the environment with such detail? |

Kyle Boisvert | ||

| 1974 |

Alice Walker's, In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens“We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and, if necessary, bone by bone” (Walker 92).Alice Walker begins the first chapter of her book, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens by mentioning her encounter with racist anthropologists in the late 1970s while researching material on voodoo practices for her book. She claims that her disappointment with the material she found from these anthropologists and folklorists stemmed from their idea that black people were “inferior, peculiar, and comic”. This account at the beginning of the chapter can be seen as a rhetorical move from Walker because it sets up a lens for the reader to view the rest of her chapter/book with. The first chapter that we read from Walker touches on the fight against censorship and silencing of black people, particularly black women artists, along with the importance of legacy, survival, and generational storytelling. Through Walker’s praise of Zora Neale Hurston, she touches on the importance of authentic portrayals of the lives and cultures of black Americans giving an example of how her relatives, who grew up in the South but moved to New York, reacted when they read Hurston’s Mules and Men. Walker states that this book worked in bringing back “all the stories they had forgotten or of which they had grown ashamed of” and in turn showing them how valuable and priceless those stories really were (85). This example is important for the understanding of this chapter because it touches on Walker’s idea of racial health where we would see and have “a sense of black people as complete, complex, undiminished human beings” within the way they are portrayed by society, something that she feels is lacking in black writing and literature. Walker also makes a point to mention that most contemporary black Americans believed at some point that their “blackness was something wrong with them” (86). Walker connects this to her point about a lack of racial health because as she says with the white racist anthropologists, perceptions of black culture and people, in general, were that they were inferior, peculiar, and comic in relation to white people. This effect of this perception being the only narrative readily available and persistent in society led to many black Americans eventually believing it to be true, losing part of their agency, self-respect, and forgetting the beauty and value of their own culture. Walker states that “America does not support or honor black people as human beings let alone black, women, and artists so they have to take the assistance they can in order to secure that their cultural heritage would survive and their writing would be preserved“ (91). This was said in response to her mention that even Zora, the self-respecting author, became timid in her writing and her words became false due to her financial reliance on “white folks” but as the quote says Zora sacrificed part of her own integrity so that she would be able to preserve her writing and secure her cultural heritage (91). ----------------- “Guided by my heritage of a love of beauty and respect for strength- in search of my mother’s garden, I found my own” (Walker 243).Walker begins this chapter by talking about how poet, Jean Toomer saw black women in the Post Reconstruction South as women who had been so consistently abused, sexualized, and dimmed. Walker states that all of that abuse is believed to have made them so confused they began to believe that they were unworthy of hoping for anything more/better and in turn pushed down all of the things that made them unique, beautiful, and genius (233). This chapter really takes a close look at the history and lineage of how black woman artists got to be artists despite the extreme abuse and hardship that their mothers and grandmothers endured. Walker asks “What did it mean for a black woman to be an artist in our grandmother's time?” a question that she swiftly follows up with accounts of abuse and hardship of being kept as a slave, working for ignorant people who weren’t able to see how valuable and beautiful these black lives were. This account of the abuse then leads her to ask about how, even through all of that, the creativity of black women could stay alive? Walker states that she turned to her own mother to try and answer this question and she found that even though her mother was working all of the time and rarely had a moment to be alone with her thoughts, she expressed her creativity through the materials and mediums that society presented to her, whether that was through the oral stories that Walker’s mother told her at bedtime or the garden that she tended to. Walker says that these mothers and grandmothers, despite the hardship and abuse they endured, found ways to pass on the creative spark that they couldn’t quite see actualized themselves but that they knew had value to be passed down. |

Jacquelyn Delgado | ||

| 2010 |

Generational Storytelling |

Nichole Mitchell |