Timeline: Race, Gender, Class, Sex

Created by Dino Franco Felluga on Wed, 08/19/2020 - 16:28

Part of Group:

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa. Autumn 1887 |

"Ten Days in a Mad-House" ReleasedNellie Bly, an American journalist, releases her book, Ten Days in a Mad-House. The book reflects Bly’s ten day experience going undercover into a female only insane asylum. The asylum was located on Blackwell Island, which was filled only by the asylum, a poorhouse, a smallpox hospital and a prison. She describes the asylum as so horrid that it made her “look insane.” The asylum was freezing cold with poor food and consisted of several women who had no reason to be there. Some were immigrants and were mistakenly committed to the asylum because they couldn’t understand English, and some were just poor and believed they were going to the poorhouse on the island. Not long after her book was published and received overwhelming support, the asylum was given $1 million more dollars to improve the conditions. Bly broke barriers as being one of the first successful female journalists and earning a reputation as a “stunt girl.” Bly was under an immense amount of pressure, as neither her nor her editor believed she’d be able to convince experts that she was insane and needed to be admitted into an asylum. To make her act believable, she explains that she looked in the mirror and tried to reflect all qualities she has seen in “crazy people.” Her alias was a Cuban immigrant who suffered from amnesia. She would stay in boarding houses and refuse to sleep or eat and would wander around and yell out random phrases. Eventually, one of the assistant matrons called the police and she was then admitted into Blackwell Asylum. While in the asylum, Bly explains that she acted somewhat calm and the doctors and officers would say there was no hope for her to recover because she was “positively demented.” She writes that these doctors did not really know for sure if these people belonged in an asylum. In the asylum, Bly met many different people who she didn’t feel belonged in the asylum. One was a German woman who spoke very little English and could not put together a case that the court would understand to prove she was not crazy. This woman was sent away for life “without even being told in her language why and wherefore.” There were over 1600 women in the asylum, with poor conditions throughout. These conditions made the women sick and would often make them seem crazier than they really were. They were treated inhumane, and when Bly was able to be released from the asylum, she published this book and gained the attention of people in high power. They were able to expand the budget of the asylum which improved the conditions tremendously. Bly’s written experience was a major step in reforming asylums and stopping the racism and sexism that were the cause of thousands of people’s admittance.

Source: Bly, Nellie. Ten Days in a Mad-House. 2017. Associated Articles: Blackwell's Island (Roosevelt Island), New York City (U.S. National Park Service). www.nps.gov/places/blackwell-s-island-new-york-city.htm. |

Kelly Matsuoka | ||

| 28 Jul 1893 to 19 Sep 1893 |

New Zealand: The First Country to Grant National Voting Rights to WomenOn July 28th, 1893 a suffrage petition signed by 'Mary J. Carpenter and 25,519 Others' was submitted to the New Zealand Parliament. Less than two months later on September 19th, 1893, Lord Glasgow, governer of New Zealand during the time period, signed a new Electoral Act into law. With the signing of this act, New Zealand was the first self-governing country in the world that enacted women's right to vote in elections. This was a huge step in the world wide women suffrage movement, although most other democracies, such as Britain and the United States, did not give women the right to vote until after World War 1. The passing of the Electoral Act was made possible by the years of effort from suffrage campaigners in the country that were led by Kate Sheppard who also founded the Women's Christian Temperance Union two years before becoming the leader of the suffrage movement in New Zealand. A series of massive petitions written with the act of calling Parliament to grant women's right to vote took three years to compile together before they were able to submit the entirety of the New Zealand Women Suffrage Petition that had 25,520 signatures in total on it. The peitition stetches more than 270 meters long and is on display at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington. After New Zealand granted women the right to vote, the British Colony of South Australia was the next to follow, granting full suffrage in 1894. The start of the 20th Century saw the effect of these great advances in the suffrage movement spread to many other countries around the world and sparked the passing of many laws in support of women's suffrage. Works Cited: “Kate Sheppard.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 2 Apr. 2014, www.biography.com/activist/kate-sheppard. “Suffrage Petition, 1893.” New Zealand Government, 13 Mar. 2018, nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/womens-suffrage/petition. “Women and the Vote.” New Zealand Government, 20 Dec. 2018, nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/womens-suffrage. Women's Suffrage Movement - Facts and Information on Women's Rights. www.historynet.com/womens-suffrage-movement. |

Vanessa Heltzel | ||

| Apr 1895 to May 1895 |

Trials of Oscar Wilde

ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 3 Apr 1895 to 25 May 1895 |

The Trials of Oscar WildeOscar Wilde, born on October 16, 1854, was widely known across London as one of the most popular poets and playwrites, but later became more known for his trials and later criminal conviction for "gross indecency" under the 1895 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which made it a crime to commit any acts of "gross indecency," or in other words, incriminate anyone who performs sexual activity with another individual of the same sex. Wilde was put on trial because of Lord Alfred Douglas' father, John Sholto Douglas, who was concerned about the relationship Wilde had built with his son. The trials of Oscar Wilde caused homosexuals to become more of a threat to the public eye, and people were much less tolerant of them. Same sex couples who were looked over before the trials became suspect after, and people in same sex friendships became anxious of giving the public reason to believe they were in a sexual relationship. Art also began to be associated with homo eroticism, and feminine characteristics in a man immediately offered the idea of homosexuality. Works cited: Linder, Douglas O. The Trials of Oscar Wilde: An Account. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/wilde/wildeaccount.html |

Grace Kuhlman | ||

| 11 Oct 1899 to 31 May 1902 |

Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 17 May 1900 |

Siege of Mafeking lifted

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 30 Nov 1900 |

Death of Wilde

ArticlesEllen Crowell, “Oscar Wilde’s Tomb: Silence and the Aesthetics of Queer Memorial” Related ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Jun 1901 |

Hobhouse report on Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 1909 |

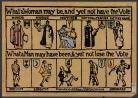

Clemence and Laurence Housman found the Suffrage Atelier "What a woman may be, and yet not have the vote". This banner was produced at the Suffrage Atelier in 1912. Wikimedia Commons. Following the formation of the Artists' Suffrage League, founded by renowned stained glass artist, Mary Lowndes, in 1907, which produced illustrated banners, postcards, and pamphlets used to promote the campaign for women's enfranchisement in Britain and North America, Clemence and Laurence Housman established their own Suffrage Atelier in 1909. Its practices took place at artists' homes, before the Housman siblings offered the site of their small home, Pembroke Cottage in Kensington, as its headquarters. Though the location of its headquarters would change three more times within its five operational years, the collective vision of the Atelier remained the same: it was to act as an arts and crafts society which worked towards the enfranchisement of women, with an additional effort to encourage artists to forward the women's movement by means of pictorial publications. (VADS, "The Women's Library: Suffrage Banners") In contrast with its predecessor, the Artists' Suffrage League, the Housmans' Suffrage Atelier encouraged non-professional visual artists and enthusiasts to submit their work to the cause in addition to professional artists, and also offered a small percentage of the sold works' profits as compensation. The Atelier also contrasted with its associates, the Women's Freedom League (1907-61) and the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) (1903-17), stylistically, by means of the colours its members chose to use in the creation of its feminist propaganda. While the other organizations used white, green, and purple, which are commonly known as the defining colours of the suffrage movement, the Atelier used a broader range of hues, as depicted in one of its banners (at left), wherein blue, black, and gold are used. Clemence led the team, and also lent her talents as an embroiderer, illustrator, and wood engraver to the Atelier, often spending entire days sitting on a floor cushion, doing her needlework or engraving in order to benefit the cause. Laurence designed a number of the Atelier's banners. As Clemence Housman was a respected member of the WSPU, much of the Atelier's work could be found for purchase within its store chains and also within the pages of its national newspaper. The Atelier held printmaking workshops and competitions in addition to the numerous exhibitions, political rallies and processions its members would regularly attend and circulate their artwork at, while also allowing for new and meaningful relationships to be forged between women as they worked collaboratively to aid a feminist cause which married the artistic with the political. The feminist nature of the workshop's artistic operations also subverted the common belief that embroidery and needlework reinforced women's domestic place within the home. The Suffrage Atelier ran from 1909-14. (Morton, "Changing Spaces: Art, Politics, and Identity in the Home Studios of the Suffrage Atelier") |

Alex Heath | ||

| circa. 1940 to circa. 1973 |

Homosexual Aversion TherapyHomosexual aversion therapy notaby began in the early 1940s. Homosexuality, bisexuality, and transsexuality were viewed as sexual deviances caused by psychological maladaption. Queer patients were often taken to mental asylums involuntarily by family to be "cured", and aversion therapy was one of the many methods scientists attempted to do this. It was believed that conditioning patients to associate the sex they found attractive with unpleasant stimulus would cause them to lose their attraction and turn heterosexual. Doctors would take patients to viewing rooms and project images of people each patient would be attracted to. If they showed any signs of attraction or interest in the picture, the doctors would administer the unpleasant stimulus. The most notable of these stimuli was electroshock waves. Injecting drugs into the patient to cause nausea and vomiting was also common. Eventually, patients would associate these images with the shocks or drugs, and would be averse to looking at the screen. Continued exposure showed that, after time, this dislike would also be applied to real time, and patients would get upset looking at any member of their once-preferred sex. The cruelty of aversion therapy and other conversion methods eventually became a talking point in the psychological field. Human rights activits began to work for protections of queer people and make involuntary conversion illegal. As the century progressed, aversion therapy waned in popularity. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Associaton removed homosexuality from its list of diagnosable mental disorders. Treatment for the "condition" was no longer sanctioned. While this did not end the practice of aversion therapy, it did limit it, and the controversy around the practice made it extremely unpopular as more time passed. Today, queer aversion therapy is illegal in many states or countries. It is still used in some states, and has been expanded to try and deter sexual offenders like pedophiles. Sources: Blakemore, Erin. "Gay Conversion Therapy's Disturbing 19th Century Origins." History.com, 2019, www.history.com/news/gay-conversion-therapy-origins-19th-century. Accessed 7 October 2020. Chenier, Elise. “Aversion Therapy.” GLBTQ Archive, 2015, www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/aversion_therapy_S.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2020. Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. Aversion Therapy. 23 Nov. 2018, www.britannica.com/science/aversion-therapy. Accessed 9 October 2020. |

Allison Hicks |