Victorian Novels of Class, Gender, Race, and Empire Timeline

Created by Bettina Pedersen on Mon, 09/20/2021 - 13:16

This timeline will span that timeframe covered by the five Victorian novels included in our course and their authors.

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1856 |

Marian Writes Crucial EssaysIn this year, Marian writes some of her most crucial essays of her career: "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists" and "The Natural History of German Life." Marian is firmly set in the literary scene at this point, having written for The Leader and Westminster Review extensively for about a year. As an estalbished writer, Marian will be able to write her novels from a secure and established position. Eliot, George. Middlemarch, edited Gregory Maertz. Broadview Editions. 2004 |

Emma McCoy | |||

| 1857 |

Marian Evans uses pen name: George EliotIn 1857, Marian Evans used the pen name, George Eliot, for the first time when she published, "Amos Barton," "Mr Gilfil's Love-story" and "Janet's Repentance" in Edingburgh Magazine. She continued to publish under this pen name when she turned to novel writing and it persisted through to the publication of Middlemarch in 1872.

Eliot, George, and Gregory Maertz. “Chronology.” Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ont., 2004. |

Anthony Calvez | |||

| 1857 |

The Indian Uprising of 1857The Indian Uprising was caused by an cultural and religious issue over gunpowder cartiges. The cartiges used by the Bengal army were required to be opened with ones' teeth, but were believed to be purposely greased with cow or pig fat. The consumption of such animal products was as insult to both Hindu and Muslim religions--cows were considered holy to the Hindus and pigs were considered unclean to the Muslims. The Half-Caste by Dinah Mulock Craik was originally published in 1851 Chambers's Paper for the People (vol. 12, no. 94) and brought to light many biased inequalities that could have been resolved. The "Introduction" by Melissa Edmundson references this revolution because the ideas of disrespect and inequal treatment this work that brings light can be seen influencing the revolt. A new edition was published in the same year of 1857, which I base my analysis on.

Craik, Dinah Mulock, and Melissa Edmundson. “Introduction.” The Half-Caste, edited by Melissa Edmundson, Broadview Editions, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 2016, pp. 9–37. |

Rachel Heckle | |||

| circa. 1858 to circa. 1947 |

Indian Civil ServiceA division of government that began in 1858 was started by the British Empire. It was a very small administrative section of government. Within the office, there were elected officers that competed to be included. These officers supervised and controlled the region and the lower ranks. The lower ranks were clerks and provincial staff that did individual smaller tasks that made up the inner workings of the government. The ICS officers headed the entire operation. They were in charge of every district and oversaw every other small government and were the main leaders of British India. The division was dismissed along with the British rule in India in 1947. After Mr. Grant finished school he entered the Indian Civil Service. Ewing, Ann. “Administering India: The Indian Civil Service.” History Today, History Today Ltd. Company, 2021, https://www.historytoday.com/archive/administering-india-indian-civil-se... Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited Tabitha Sparks. Broadview editions 1887. |

Hope Tyler | |||

| 1858 to 1900 |

Ethnic Classification during Victorian PeriodWhat surprised me about this book was the multi-tiered classification system used by British Citizens to classify the mixed percentages of individuals who possessed both some combination of British and Indian blood. Each classifications lead to both advantages and disadvantages within the Indian and British communities at the time: “‘Anglo-Indian’ meant ‘ those who have either no or very slight admixture with the native races’; ‘Eurasians’ were ‘those in whom the European and native descent are more evenly balanced’; and ‘East Indians’ were ‘those of remote European descent and approaching more closely to the native type’” (Craik, 14). Here are just three of the different classifications, but even within these three divisions of race, one can find subsets that would further divide individuals among racial lines. This knowledge helps the reader to indicate why there is such a large disparity between how the more British half-caste is treated compared to the more Indian half-caste.

Craik, Dinah Mulock. The Half-Caste, edited by Melissa Edmundson. Introduction: footnote 1, The Anglo-Indian (9 January 1886): pp. 19, by Melissa Edmunson. Broadview Editions, 2016. |

Brennan Ernst | |||

| 1858 |

Craik on Gender RolesIn 1858 A Woman's Thoughts about Women was published, 7 years after The Half-Caste. In the work, Gaskell discusses the nature of gender and argues that current gender theory "totally [ignores] the fact that each sex is composed of individuals, differing in character almost as much from one another as from the opposite sex" (90). This later thought has roots in The Half-Caste because we have Miss Pryor deciding that she's on her own when it comes to Zillah and she shoulders the responsibility (71). Craik believes in how women are capable and shouldn't be shoved into a box as a whole sex. Craik, Dinah Mulock. The Half-Caste, edited Melissa Edmundson. Broadview Editions, 2016 |

Emma McCoy | |||

| 1864 |

Dinah Mulock Craik: Awarded the Civil List PensionIn 1864, Dinah was awarded the Civil List Pension, one of the few awards given to British writers at the time, for her services in literature. A Civil List pension is an honorary pension paid by the government as thanks for service. It was originally created to pay expenses for the sovereign and their families. Dinah used her pension to help struggling women writers. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Civil-List |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 1865 |

The Salvation ArmyThe Salvation Army is a Christian organization founded in London by William and Catherine Booth. Originally Methodists, the Booths began preaching to those rejected by orthodox Christian organisations in an attempt to be inclusive of all potential followers of Christ. This organized preaching began in 1865 under the name "The Christian Mission," and in 1878 they renamed thesmelves, The Salvation Army. The group is organized like the military, with priests being assigned the rank of officers, and they're organization is comprised of both men and women in leadership roles. This organization played a major part in providing services and allocating resources to the poor and the ostracized population of London. In Maragaret Harkness' novel, A City Girl (1887), Nelly is able to find shelter and aid from a Captain of The Salvation Army. The group was welcoming to fallen women, pregnant women, and women in need and offered the resources to help Nelly through her pregnancy and raising her baby.

The Salvation Army's International Headquarters Communications. “Transforming Lives since 1865 – the Story of the Salvation Army so Far.” Transforming Lives since 1865 – The Story of The Salvation Army so Far, https://story.salvationarmy.org/.

|

Anthony Calvez | |||

| 1865 |

Elizabeth Gaskell's deathElizabeth Gaskell passed away on November 12, 1865. She had been touring a retirement home for her husband and family in Holybourne in Hampshire. She suffered from a sudden heart attack at the age of fifty-five years old. Her last written work, the novel “Wives and Daughters” was never published. However, after her death, it was published posthumously in Cornhill Magazine in 1866.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Mary Barton edited Jennifer Foster. 1848, Broadview Literary Texts. “Elizabeth Gaskell Biography.” The Gaskell Society, The Gaskell Society, 5 Mar. 2020, https://gaskellsociety.co.uk/elizabeth-gaskell/. |

Hope Tyler | |||

| 1865 |

Dinah Mulock Craik MarriesAlthough she was a successful author and writer on her own, Craik eventually did fall in love and married George Lillie Craik in 1865. They married in Bath on April 29th. Connections can be made to the strength of Miss Pryor of The Half-Caste (1851) as she was autonomous and making her own decisions without a husband. While some amy be disappointed that she didn't live her life fully single, I would argue that she found love on her own terms. Craik, Dinah Mulock. The Half-Caste, edited Melissa Edmundson. Broadview Editions, 2016 |

Emma McCoy | |||

| 1868 |

Position of the Governess in Victorian SocietyIn The Half-Caste, the narrator of the story finds herself in a little bit of a quandary concerning the income of both she and her mother. Cassandra must find work in order to support herself and her mother, so she is thrust into the job of governess. She did not go to school to become a governess, but from the education she received because of her class status, she is able to scrape by and become an adequate governess for the Pryors. However, in appendix C–which deals with the role of the Victorian Governess–we find out more about the contemporary qualities that were desired in a governess at the time: “There are strong objections in the minds of some, to a lady who is compelled unexpectedly to teach, and to teach just for a living” (Craik, 144). According to this source, the circumstances that lead Cassandra to become a governess were less than ideal. She was not fully equipped to assume the role of governess. Despite some of these sentiments floating around at the time, Craik creates Cassandra to be an adept governess that looks out for the well-being of her pupil, Zillah. Craik, Dinah Mulock. The Half-Caste, edited by Melissa Edmundson. Appendix C, From Emily Peart, A Book for Governesses (Edinburgh: W. Oliphant, [1868]), 9-22. Broadview Editions, 2016. |

Brennan Ernst | |||

| 1 Jan 1869 |

Dinah Craik AdoptsIn January of 1869, Dinah adopted an abanded baby girl named Dorothy. The baby was found behind a stack of bricks in the London suburb of Bromley. 18 years later, she published The Half-Caste where the main character took a motherly position over an orphaned girl named Zillah. It appears this disposition of care has been a part of Dinah's character all along. https://omekas.library.uvic.ca/s/crafting/item/5840

|

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 1870 |

The Education ActThe Education Act, also known as the Forster’s Act allowed for school boards to require the education of local towns. It was an attempt to educate children especially in the East End of London. That way they could be educated and might break away from the routines of the working-class generations before them. The act was enforced in 1870 but revisions of the act happened in 1876 and 1880. The revisions expanded the number of East End children going to school, however, it took them away from work. They were no longer able to earn money for the households which became problematic for a while. This act was still in use at the time of A City Girl and most children were being taught basic education.

Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited Tabitha Sparks. Broadview editions 1887. |

Hope Tyler | |||

| 1870 |

The Education Act of 1870Also known as the Forster's Act, it allowed school boards to make education complusory at the local level. This act affected the children between ages 5 and 12 in England and Wales. This was seen in footnote 1 of page 43 in A City Girl, when it came to disussing about the school children smiling at the blackboard. "Later versions of the act (1876, 1880) helped to increase the number of East End children in schools, but their removal from wage-earning oppurtunities was not unproblematic" (footnote 1)

|

Jorge Sandoval | |||

| 1871 to 1872 |

Publication of MiddlemarchMary Ann Evans took three years to write and publish one of her most famous works Middlemarch. The first book was published in December but there would be seven more to follow over a period of time. Each part had characters whose lives interacted with each other in the town. That way readers could have different parts of Middlemarch, but the characters were recurring. Each section cost five shillings each and the books continued to be published throughout the year.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. edited Gregory Maertz. Broadview Editions. 2004 |

Hope Tyler | |||

| 1871 to 1872 |

How Middlemarch Was Originally PublishedIt’s important that contemporary readers remember how Middlemarch was originally published. It did not come out in one single book, but instead in 8 different parts. One part for each of the ‘books’ that divides up the entirety of the work. From December 1871 to December 1872, the publisher Blackwoods published Eliot’s impressive novel. The basis of Middlemarch stems from two separate stories: one that follows a doctor who is bent on reforming the medical practices of England at the time and the other that follows a young woman who is intent on scholarship and achieving her dreams of developing her mind. Eliot took around 5 years to complete the whole novel. The recent publication of the journals she kept while writing her masterpiece has shown the public the lengths she went to study and research important topics that appeared in her book.

Uglow, Nathan. "Middlemarch". The Literary Encyclopedia. First published 01 April 2002 https://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=3605. |

Brennan Ernst | |||

| 1872 |

First Edition of Middlemarch Published After SeriesAfter the success of Middlemarch, published in a series throughout the years of 1871-1872 as a way to make the novel less expensive and thus more accessible to the literate public, the novel was compiled together in 1872 from this series to form the first edition of Middlemarch, consisting of four volumes. Gaskell opposed the separating of her novel into segments, but the publisher ignored her requests. However, Gaskell's publisher worried about the continued interest in following the full novel as each of Middlemarch's books was independent. Nonetheless, the novel was a success, leading the the four-volume's publication out of the three-volume format typical of the time.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. Edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview Press, 2004. Wikipedia contributors. "Middlemarch." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 18 Oct. 2021. Web. 6 Dec. 2021. |

Rachel Heckle | |||

| 1880 |

The Employer’s Liability ActThe beginning of the British Labour reforms regarding workers compensation. This act stated that an employer could be held liable for injuries that occur in the workplace if proven that they wer inflicted by faulty machinery, negligence, or directly from another employee. While discussing her work conditions and coworkers, Nelly wishes that she could punish a coworker for physically disciplining that coworker's children; however, Nelly stops because the "law prevented" (66). Nelly has a soft heart that breaks when she hears children beaten by their drunk or otherwise parents. She recollects earlier in the chapter that intervening, even if legal, would not help the situation and could make the situation worse. This act was later repealed in 1897 by the Workman's compensation act that made employers liable for all workplace accidents without required proof of who inflicted the injury but rather proof that the injury occurred in the place of employment during working hours.

Harkness, Margaret, and Margaret Harkness. “Chapter IV. An East-End Theatre.” A City Girl: A Realistic Story, edited by Tabitha Sparks, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 2017, pp. 65–71.

Wikipedia contributors. "Employers' liability act of 1880." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 12 Oct. 2021. Web. 1 Dec. 2021. |

Rachel Heckle | |||

| circa. 1880 |

"Slumming" in the East EndIn the late Victorian era London's East End became a popular destination for slumming, a new phenomenon which emerged in the 1880s on an unprecedented scale. For some slumming was a peculiar form of tourism motivated by curiosity, excitement and thrill, others were motivated by moral, religious and altruistic reasons. The economic, social and cultural deprivation of slum dwellers attracted in the second half of the nineteenth century the attention of various groups of the middle- and upper-classes, which included philanthropists, religious missionaries, charity workers, social investigators, writers, and also rich people seeking disrespectable amusements. As early as in 1884, The New York Times published an article about slumming which spread from London to New York. Slumming commenced in London […] with a curiosity to see the sights, and when it became fashionable to go 'slumming' ladies and gentlemen were induced to don common clothes and go out in the highways and byways to see people of whom they had heard, but of whom they were as ignorant as if they were inhabitants of a strange country. [September 14, 1884 ] In the 1880s and 1890s a great number of middle- and upper-class women and men were involved in charity and social work, particularly in the East End slums. The national press covered widely shocking and sensational news from the slums. Anxiety and curiosity about slums could be heard in many public debates to that extent that, as Seth Koven writes: By the 1890s, London guidebooks such as the Baedeker’s not only directed visitors to shops, monuments, and churches but also mapped excursions to world renowned philanthropic institutions located in notorious slum districts such as Whitechapel and Shoreditch. [1] In fact, for a considerable number of Victorian gentlemen and ladies slumming was a form of illicit urban tourism. They visited the most deprived streets of the East End in pursuit of the 'guilty pleasures' associated with the immoral slum dwellers. Upper-class slummers sometimes spent in disguise a night or more in poor boarding houses seeking to experience taboo intimacies with the members of the lower classes. Their cross-class sexual fellowships contributed to diminishing class barriers and reshaping gender relations at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, slumming was not only limited to odd amusement. In the last two decades of the Victorian era a rising number of missionaries, social relief workers and investigators, politicians, journalists and fiction writers as well as middle-class ‘do-gooders’ and philanthropists made frequent visits to the East End slums to see how the poor lived. A number of gentlemen and lady slummers decided to take up temporary residence in the East End in order to collect data on the nature and extent of poverty and deprivation. Some slummers were disguised in underclass drags in order to transgress class boundaries and mix freely with the poverty stricken inhabitants of the slums. Written or oral accounts of their first-hand observations arose public conscience and motivation to provide slum welfare programmes, and prompted political demands for slum reform. The last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed the upsurge of public inquiry into the causes and extent of poverty in Britain. Some of the most outstanding late Victorian slummers were Princess Alice of Hesse, the third child of Queen Victoria; Lord Salisbury, and his sons, William and Hugh, who resided temporarily in Oxford House, Bethnal Green; William Gladstone, and his daughter Helen, who lived in the south London slums as head of the Women's University Settlement. (Koven 10) Even Queen Victoria visited the East End to open the People’s Palace in Mile End Road in 1887. Benevolent middle- and upper-class women went to slums for a variety of purposes. They volunteered in parish charities, worked as nurses and teachers and some of them conducted sociological studies. Such women as Annie Besant, Lady Constance Battersea, Helen Bosanquet, Clara Collet, Emma Cons, Octavia Hill, Margaret Harkness, Beatrice Potter (Webb), and Ella Pycroft explored some of London’s most notorious rookeries, and their eye-witness reports gradually changed the public opinion about the causes of poverty and squalor. By the turn of the nineteenth century thousands of men and women were involved in social work and philanthropy in London slums. |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 2 Dec 1880 to 22 Dec 1880 |

Death of Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot)Mary Ann Evans, known by pen name George Eliot, spent a long life of writing down many novels, most notably Middlemarch. This demonstrated what a wonderful author she was, having made many interesting pieces of readings for many to enjoy. She was married to George Henry Lewes, the editor of The Leader, in 1855 where they were happy together for many years to comes, until 1878 where he passed away. She proved how much she cared for him bu finifhinsg the final volume of Lewes's Problems of Life and Mind. Eventually she would meet John Walter Cross, originally giving him Italian lessons until she agreed to marry him in 1880. At the same year they moved to Cheyne Walk, where she caught a cold and died toward the end of the year. She was buried next to her first husband, while her second husband made a biography of George Eliot. Overall, this shows that she did indeed have lived a good life, she cared for her first husband by finishing his work and then was buried next to him. So in return, it was right that her second husband got to write about her as well.

Wiesenfarth, Joseph. "George Eliot." Victorian Novelists Before 1885, edited by Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman, Gale, 1983. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 21. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/H1200002772/LitRC?u=sand82993&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=e989404b. Accessed 12 Nov. 2021. |

Jorge Sandoval | |||

| 1882 |

Married Woman's Property ActMarried Women’s Property ActAs per English common law, women did not have any right to dispose of property or to make a will after marriage without the consent of their husband. Only widows could claim any property for themselves. Most of the property of the woman before marriage (obtained from the father), and after the ceremony, the husband got this property. This was enforced by the Common Law Doctrine of Coverture. If you compare the rights of a married and unmarried woman, the unmarried woman had much more rights than the married woman had. Unmarried women could buy and sell property, make wills, and have total control over all things they owned. Also since many people realised that only a minority of women got married for love, the question was why get married at all? The reason of marriage for many women, in spite having to give up their property, inheritance, and freedom, was to marry into a higher social status. A woman wanting to divorce her husband was looked down upon; also they would not be given any of their property owned before marriage. So, a majority of widows, who were left with only 1/3 of their husband’s property, preferred to remarry to have protection under the law for their children. Prime Minister William Gladstone, in 1882, passed Married Women’s Property Rights Act. This gave married woman equal rights to the average unmarried woman. Although they did not have equal rights as their husbands, this was nevertheless a huge progress for the married woman. Under the Married Women’s Property Act, a married woman could keep their inheritance and property post marriage, but still needed the consent of her husband in buying or selling of the property. |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 1885 |

Entertainment in The Albert PalaceThe Albert Palace is a place in A City Girl that Jack, Nelly, George, and Mr. Grant go to on their day off. At Albert Palace, citizens were able to visit and spectate a good number of different activities like exhibitions, theatrical and dance performances, gardens, and various other entertainments (57). The building is located in Battersea, in the borough of Wandsworth, London. One of the main attractions of the Palace was its gardens. They were designed by Sir Edward Lee with terraces standing next to the main Prince of Wales Road entrance. The gardens contained many different features like fountains, a conservatory, and a bandstand. The Albert Palace interested me because it was one of the only places that I saw in the readings where the lower class characters were congregating for pleasure. In books like Mary Barton, the characters were too poor to afford any form of entertainment. It was cool to see the situation for citizens that were in the upper half of the working class like Nelly and George.

Wikipedia contributors. "The Albert Palace." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 9 Mar. 2020. Web.

Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited by Tabitha Sparks. Broadview editions 1887. |

Brennan Ernst | |||

| 1886 |

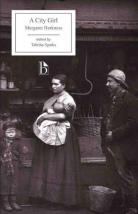

Robert Harkness Dies and Margaret Harkness Becomes RadicalRobert Harkness, father to Margaret Harkness, passed away in 1886. As an Anglican priest, Robert had much influence over Margaret's religious life and subsequent views. After her father's death, Margaret becomes involved in many radical political movements to help prevent or alieve poverty in the East End, even adopting the pseudonym "John Law" to publish her writings in favor of the movements. A City Girl is among several works of Margaret's attempting to bring attention to the poverty of the East End against the comfortability of the West End of London and the political divisions between the working and middle class.

Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl: A Realistic Story, edited by Tabitha Sparks, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 2017. |

Rachel Heckle | |||

| 1887 |

Margaret Harkness Publishes A CITY GIRL: A REALISTIC STORYIn 1887, Margaret Harkness, under the pen name John Law, published a novel called, A City Girl: A Realistic Story. It told the story of a bright-eyed young woman named Nelly who endured the hardships of poverty-stricken East End London. |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 1887 |

Margaret Harkness publishes first novelIn 1887 Margaret Harkness published her first novel A City Girl: A Realistic Story. This work was considered a slum novel and it was not the first of its kind set in the East End of London in the 1880s. She published the work under the name John Law. She adopted this pseudonym in 1886 and used it for most of her writings. The Vizetelly & Co. Intermittent work in Scotland became her publisher on behalf of Keir Hardie.

Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited Tabitha Sparks. Broadview editions 1887. |

Hope Tyler | |||

| 1905 |

The Aliens Act of 1905The Aliens Act of 1905 was a watershed in British history, marking as it did a victory for the opponents of unrestricted alien access into Britain. It was significantly the first such legislation to be passed in peacetime. In the context of what was to follow, it was the point at which the liberal, ‘Open Door’ approach to immigration began to close; a process that continued throughout the twentieth century. |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 2 Dec 1910 |

Dinah Craik's, John Halifax - Hits the Movie ScreenCraik wrote her most popular work in 1857 titled John Halifax, Gentleman. It was made into a silent film in 1910. Later, in 1938, this film was made again in the U.K. and starred actors John Warwick, Nancy Burne, and Roddy McDowell. It tells the story of John Halifax who, despite humble beginnings, becomes a highly respected local businessman. As partner in a mill he weathers the turbulent economic times of the early 1800s. It was also adapted for television by the BBC in 1974. |

Charmen Atchison | |||

| 1921 |

Harkness publishes last known workA Curate's Promise is published in 1921 and she dies two years later. This last publication continues to focus on the Salvation Army and their efforts to help the urban poor. Harkness, who often published under the name Law, finishes her career with this work, showing that she remained focused on the plight of the poor. Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited Tabitha Sparks. Broadview Editions, 2017 |

Emma McCoy | |||

| 1923 |

Margaret Harkness DeathHarkness spent much of her life traveling throughout the continent working and writing for various jobs and magazine or newspaper companies. She came back to London to be with her mother while she was ill. Once her mother passed away, Harkness traveled back to the continent. Two years after the publication of her last novel Harkness died at the Pensione Castagnoli in Florence on 10 December 1923. She was buried the next day at a local cemetery. She was identified on her death certificate as a spinster of independent means.

“Margaret Harkness (1854-1923).” Victorian Secrets, Victorian Secrets Limited, 15 Sept. 2015, https://victoriansecrets.co.uk/authors/margaret-harkness/. Harkness, Margaret. A City Girl, edited Tabitha Sparks. Broadview editions 1887. |

Hope Tyler |