Created by Emma Jaeger on Wed, 11/03/2021 - 12:36

Description:

Since ancient European times, the term "terra australis incognita” (the unknown southern land) held in it the prospect of adventure, wealth, and glory. Theorized to be a large mass of land in the southern hemisphere to balance out the land in the north, Australia was idealized for the promise of gold and commercial riches. In 1768, after centuries of unsuccessful voyages, Captain James Cook landed on the eastern coast of Australia, claiming the continent for Britain. In a period of increasing criminal activity and quickly depleting prison system resources back home, Britain was forced to look beyond its shores for a place to stow its undesirables. With the American colonies no longer an option, England turned its head and resources to Australia, which became a place for the exile of convicts and emigration. For Dickens and the British Parliament, Australia was the place of riches it had once been rumored to be, a solution to both the struggles of the government and that of the lower class with the promise of expansion and brighter futures, where a life of hard work could result in tangible reward. For those who were forced onto its land as little more than slave laborers, though, it could be a sentence worse than death. And for the Aboriginal Australians from whom that land was stolen, the conquest and colonization of the continent was the beginning of an arduous story of oppression, erasure, and prejudice.

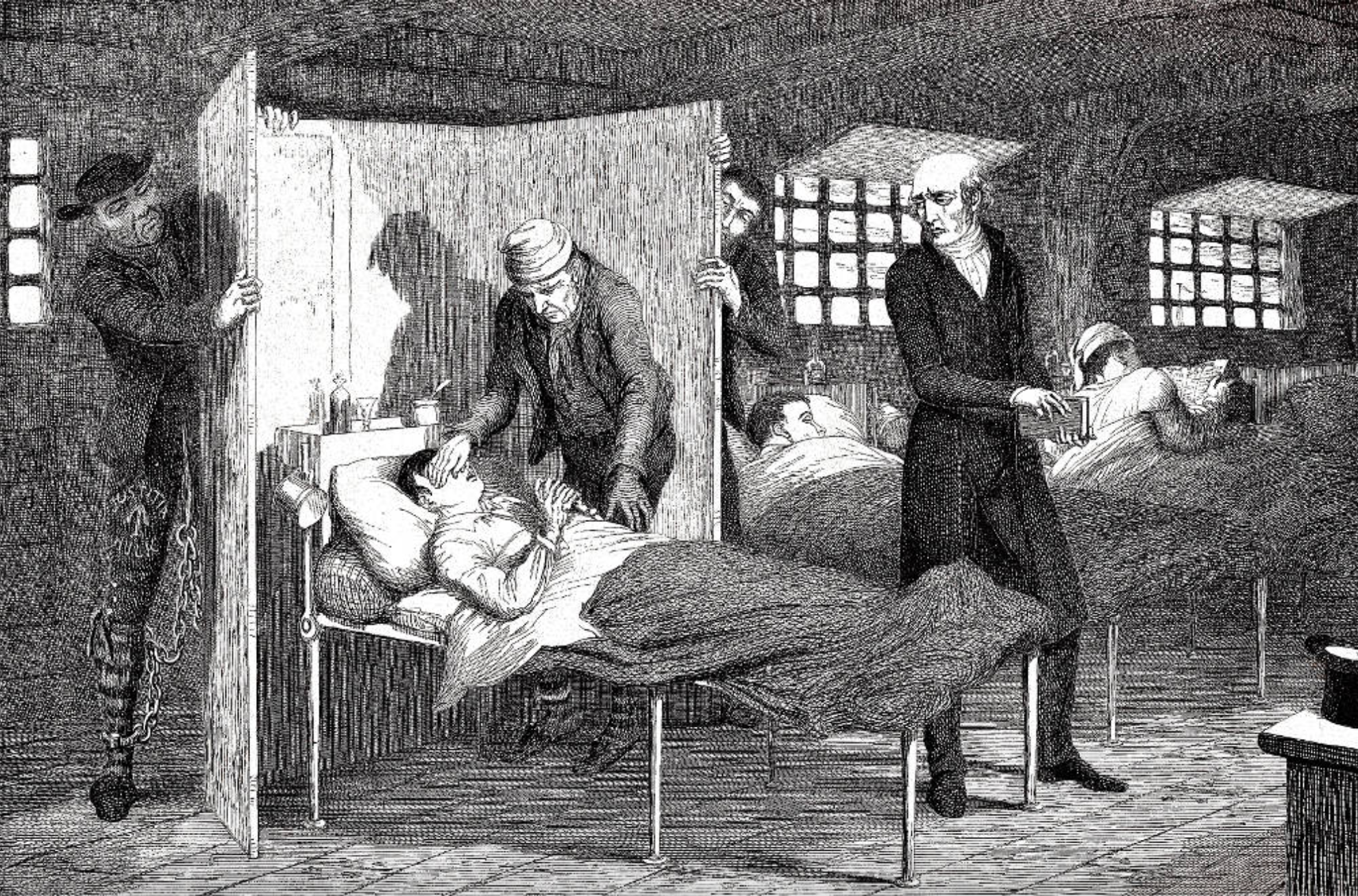

George Cruikshank, "Early Dissipation Has Destroyed the Neglected Boy. — The Wretched Convict Droops and Dies," Plate 7, The Drunkard's Children, 1848.

In 1787, the first fleet of colonists set sail for Australia and landed a year later in 1788. Part of the drive behind the colonization of Australia may have been to set up a stronghold for trade in the eastern seas. However, the more commonly known motivation was to relieve Britain’s prison systems. Britain had been sending its criminals to the American colonies, but after the American Revolution, that relief on its justice system was abruptly cut short. Prior to Australia, prisoners would perform hard labor in domestic prisons or on prison ships, but these systems quickly became overwhelmed, and Australia was the perfect solution to this overcrowding. With a need to relieve the overcrowded systems at home, and a simultaneous need for hard, cheap labor to bolster the new Australian colonies, Britain began sending convicts to Australia under the sentence of transportation with its first penal colony being New South Wales. Once there, convicts worked on government-owned farms until their sentence was served at which point they would be given their own plot of land to farm. Because it was beneficial to have free labor in Australia, transportation was the sentence for petty crimes as small as pickpocketing or stealing a handkerchief as well as prostitution. In the series The Drunkard’s Children, Cruikshank shows the now dead drunkard's son sentenced to transportation on a convict ship, dying en route to Australia.

Unknown, "Flogging a Convict at Moreton Bay," 1836.

While leaving the saturated prison systems of Britain and having a chance at freedom and land ownership might seem like a light punishment at worst, the treatment of prisoners in the Australian colonies was sadistic, including flogging as this image depicts. Upon arrival, prisoners were sorted into groups based on their skills and dressed in clothes that mimicked a joker's garb with the intent of humiliating the wearers. Unskilled convicts were loaned out to free settlers as servants, while others were forced to perform grueling manual labor under dismal conditions. While these conditions were not much worse than what could have been expected in Britain, it was the lack of humanity in their treatment by superiors that made transportation a sentence to dread. Far from the tangible reaches of Parliament, there was a corrupt sense of power and independence felt by prison authorities, and prisoners would be frequently subject to floggings. Additional punishments were the treadmill where a prisoner was made to walk up a set of revolving steps to power a mill which would grind flour or other spices. The work was tedious and exhausting, but if they misstepped, they risked the mutilation of their legs by the blades below them. The punishments for women were less violent, often involving shaving the head, and in repeat offenders, solitary confinement, which had crippling mental consequences. Bias and prejudice ran rampant among the prison guards with those who volunteered for such jobs often having a sinister motive. All in all, while transportation did result in an improved life for a few convicts once their sentences had been served, for the vast majority, it meant leaving all they had ever known to die a prisoner surrounded by desperation and suffering if they did not perish on an overcrowded convict ship before they even made it to Australian shores as Cruikshank poignantly illustrates in the first image.

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), "The Emigrants," for Charles Dickens's David Copperfield, 1850.

While Australia was a dreaded sentence for convicts, it held the promise of a better life for the lower classes in industrial Britain. With people flooding cities to take new industrial jobs, the divide between the rich and the poor was growing ever larger, and the impoverished conditions under which the latter lived were only getting worse. Fearful that their restless lower classes would follow France’s revolutionary example and needing a larger non-convict population in Australia anyway, Britain began advertising Australia as a place where less fortunate individuals could go to own land, start families, and even have servants in the form of convicts, which would have been an unattainable luxury in their mother country. This is showcased in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield when the Peggottys and the Micawbers, who have undergone loss or misfortune and face an undesirable future in Britain, emigrate to Australia. Em’ly Peggotty, in particular, exemplifies the opportunity Australia provided to women in particular. The large majority of convicts sent to Australia were men—so much so that women who wouldn’t have otherwise been punished so severely were sentenced to transportation simply to increase the female population. This meant that even Dickensian women like Em’ly and Martha Endell, who are driven to emigrate out of disgrace and would have faced unhappy futures in Britain, or women who had never been an object of desire previously, like Dickens's Mrs. Gummidge, could easily find marriage in Australia; Martha does marry. In the image above, we see David saying goodbye to the Micawbers and the Peggottys on a ship bound for Australia. While Australia held the promise of greater quality of life for colonizers, the living conditions on the ships would be crowded and busy, as Phiz authentically shows in the picture.

Joseph Lycett, "Aborigines Using Fire to Hunt Kangaroos," circa 1775-1828.

While Australia provided British citizens with the opportunity for a better life, they stole, rather than discovered, the land from the Aboriginals and the Torres Strait Islanders. Over 40,000 years ago, migrants from Southeast Asia, descendants of the first people to leave Africa up to 75,000 years ago, formed the foundation of Aboriginals and the Torres Strait Islanders. The indigenous populations of Australia depicted in this colored sketch, much like the many other indigenous populations and cultures, were decimated by European colonization. The lack of mention of the Aboriginals in David Copperfield—especially when Mr. Peggotty returns from Australia to tell of his new life there—is a conspicuous absence. Seeing as there was regular conflict between the Aboriginals and the colonizers which often included the lives of civilians, it is unlikely the Micawbers and Peggottys would not have had a shock upon realizing they had emigrated into what was essentially a warzone. This could be a result of how little knowledge the British back home had of the the existence of Aboriginals, but more likely, Charles Dickens didn’t include this detail because he politically supported emigration to Australia. David Copperfield, among his other works, advocates Australia as a place where people get their just futures—those who deserve better lives receive them, and those who deserve punishment are sentenced to transportation, like Uriah Heep. As a supporter of emigration to Australia, perhaps Dickens didn’t want to further publicize the gritty elements of survival that came with the process of settling (Warwick Hirst, "A Distant Paradise for Dickens"). Regardless of the reason, the absence of the Aboriginals in Dickens’s many mentions of Australia is representative of how the vast majority of Australian narratives, fictional or not, neglect to mention the indigenous populations from whom the land was stolen.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Part of Group:

Artist:

- George Cruikshank