The Victorian Vampyre

Created by Rebecca Nesvet on Fri, 10/11/2024 - 10:36

Part of Group:

A timeline of the development of the vampyre or vampire in British and American literature, 1800-1900.

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1813 |

The GiaourLord George Byron’s 1813 poem The Giaour, misleadingly labeled as a “fragment of a Turkish tale” in its subtitle, is a tale that serves to define the atmosphere of vampiric narratives while also framing its entire story through a lens of orientalism. Orientalism, defined in Edward Said’s 1978 book Orientalism, is a writing convention that uses myths or imitations of elements of the Eastern world, often written in western territories, to add an element of mysticism centered around those very elements. The Giaour is a piece that is directly orientalist, as it exoticizes narratives about the Ottoman Empire with a white hero in the form of the eponymous Giaour opposing and eventually slaying an antagonistic Ottoman lord. Even the existence of a vampire, defined as one who will “suck the blood of all thy race” (Byron), is framed as a legend that is not European in origin, but is instead referenced by an Ottoman narrator as a potential divine punishment for the deeds of Byron’s enigmatic rider as though it is something normal among Ottoman officials. The Giaour is heroic, in a certain sense of the word, and his romantic pursuit of Hassan’s concubine Leila is treated as a worthwhile effort; in contrast, it is simply presumed that Hassan shall murder Leila through drowning for her indiscretion so that the protagonist can seek to avenge her from this wrong, which is perceived moreso as a misdeed done unto him, the white man, than unto Leila, who is the victim of this murder. Amid the center of this discussion of orientalism is the simple fact that The Giaour is a narrative not only about a white man in opposition of a man from the Ottoman Empire, but that Byron writes a story about the Ottoman Empire and its traditions built not upon the true traditions of the many cultures that made up the empire, but instead upon numerous western-crafted assumptions that provide an easy method by which Hassan can be made into an antagonist for the story’s tragic hero as well as a narrative device Byron can utilize to display apparently outlandish or supernatural things. Orientalism is, by its very nature, something built on imperialist ideals. It is something that permeates history, and its xenophobic implications play a significant role in the entire vampire genre. Bram Stoker’s Dracula, while not necessarily orientalist, has an enormous xenophobic subtext in its portrayal of vampires not only as a foreign phenomenon that England could never have, but portraying foreigners from Eastern Europe as invaders who have come to, in the case of vampires, literally prey upon innocent English women. While cases like this do not technically involve any region further than Europe, The Giaour is an enormous example of similar conventions. Hassan is portrayed as predatory toward Leila, and therefore the Giaour’s romantic pursuit of her is portrayed as tragic; similarly, the Giaour himself is only speculated as becoming a vampire by a member of the Ottoman Empire with no attention paid to the idea that this is religiously outlandish to the Ottoman Empire. All of these ideas would recur in similarly xenophobic vampire-centric literature, and though The Giaour may not have introduced these concepts, it did carve out the conventions that would be visible in these instances. |

Conor Lowery | ||

| 1816 |

Frankenstein's Eve - 1816*DRAFT* A particularly stormy summer holiday in June of 1816, found Mary Shelley, her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, her sister, Claire Clairmont, and friends, Lord Byron, and Dr. John Polidori shut inside a mansion in Switzerland called Villa Diodati. During a three-day storm where they remained inside, Lord Byron proposed a challenge, to write a ghost story better than what they had been reading. This activity, thought of on a whim, gave birth to two works that heavily impacted the Victorian Vampire culture, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and John Polidori’s The Vampyre. John Polidori’s The Vampyre was inspired by Lord Byron’s abandoned ghost story, which was later published as The Fragment, which followed a man with an illness traveling east. Polidori took this idea and created Lord Ruthven, the mysterious, charming, and seductive vampire in his tale which was based on Lord Byron himself. This blazed the way for more Byronic vampires, transforming vampires from an ugly monster to the sexy, brooding, misunderstood characters we see in many Victorian vampire novels. While they didn’t know it yet, the impacts of the massive volcanic explosion of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 had finally reached England, leaving them with a cold and dark summer, popularly coined the year without summer. The days were far darker than it usually had been, the temperatures cooled so drastically that the agriculture was suffering, and it rained and stormed like crazy. We can see the weather’s impact on them in Polidori’s The Vampyre. When Aubry sets off to travel through the woods, much to Ianthe’s dismay, Polidori makes it clear that it gets dark before he thought it would, “he did not perceive that day-light would soon end” (Polidori). He also writes that it began to storm “immediately the sun sets, night begins: and ere he had advanced far, the power of the storm was above” (Polidori). During this, is when Aubrey hears the screams of a woman, as "the thunders, for a moment silent" leading to the horrifying vampire attack. The light seems to deter the vampire, as when he opened the door, "that gave light in the day, disturbed him; - he instantly rose, and leaving his prey, rushed through the door” (Polidori). By doing this, Polidori sets up a being who thrives in the unexpected darkness and who seems to have a weakness in the light. Polidori’s The Vampyre impacts the vampire tradition in a few ways. First, thanks to Polidori, and an unknowing Lord Byron, when we think of vampires, we often think of sexy, mysterious men with a tragic backstory rather than an ugly monster. We also find ourselves in a familiar setting when the vampire attacks, dark and stormy nights and harmed by the light.

|

Rebecca Stewart | ||

| 1819 |

The "Human Vampyre" Court CaseThe use of the phrase “human vampyre” came only a couple of months after the release of Polidori’s “The Vampyre”. Used in a court case in Cork, Ireland in 1819, it generated a lot of praise from international audiences, especially the United States. Appearing in various East Coast newspapers, such as Pennsylvania's Lancaster Intelligencer, the court transcripts received great interest due to Counsellor Charles Phillips’ extravagant monologues. Phillips was a well-educated man with immense skill in oration, assisted by his further interest in poetry and prose, maybe even those of his contemporaries. He would become well known due to his unorthodox defenses that acquitted many with his pursued references (more information listed here). The use of the “human vampyre” is an interesting one for its time in the spectrum of literary vampire history. Pointedly because of the distinction of “human” in the vampire’s classification. Creating a restriction of vampires and their traits or abilities between divisions. This brings up the question of what are the classifications of vampires. What marks a distinction between one and another, or is it the result of a victim’s casualty that defines them? In Phillips’ court case, the murderer is specifically mentioned as “human” to the killing, abuse, and manipulation of two women. Describing the man as being perfidious, adulterous, and irreligious but topped with, “betraying and destroying” while “wheedling the family” for selfish gain. Taking advantage of others through deception and stealing the trust between people. On top of that, this was during a time in Europe when religion was the name and title of every person. Even going as far as religion being the reason for vampires (vampire burials video). As such, denouncing all religions would have been a sign of betrayal to family, community, and the social ladder. Taking special consideration to be physically disruptive to the lives of others. Whether this be through chaotic conversation or billowing destructiveness. The “human” aspect contains a high effort of physicality. Thus, the “human” version of a vampire is defined by such and similar terms. These terms would dismiss the general human social values and empathy of an individual toward anyone unwilling to follow the person’s gratified selfishness. But there are also emotional vampires, vampires that, for personal gain, dwindle and manipulate the emotional capacity of their victims. A psychological concept that has been studied and built on for years. Most prominently understood as the power gained over another person through the corruption of internal social boundaries. A concept that ties hand in hand with humanity and its social interactions. Becoming innately human and part of human nature. But emotional vampirism does not require physical destruction to be draining of someone. The emotional draining can be actively pursued and altered to conform to each person’s unique boundaries. Forcing others to question themselves and their values. In other words, torturing someone through destructive immaterial choices. The end goal is to acquire self-righteousness and evoke fear (more on psychological emotional vampirism). On the other hand, some vampires are seen as supernatural, having natures that resemble that of humans. But the abilities they possess separate them from the idea of a “human,” outside that of human potential. This is the primary way of discussing the vampires through literature. Showing elements of the “human” and emotional vampire. Dracula is a perfect case of all three with his deceitfulness tied to the elusive transformations and the carnage ensued on retaliators. His supernatural feats morphed to fit into the relationship of complex vampire identities. Eveline’s Visitant marks a strong emotional tie as Eveline’s health decays through conversation with a phantom-like man who questions her life. Eliciting the subtleness of the supernatural tendencies of vampires in literature. Showing the complications of classifying where and how a vampire fits into a category. That one is not all, and all is not one. |

Tyler Albrecht | ||

| 1871 to 1872 |

La Fanu's CarmillaLa Fanu's Carmilla was originally published from 1871 through 1872. It was released in a serial narrative in The Dark Blue, a London-based literary magazine over the course of a year. The story grew in popularity due to its strange themes and ease of access to it. Joseph Le Fanu was an Irish Victorian author, known for his Gothic and horror works, although Carmilla has proved to be his most popular. Carmilla's gothic themes, like other Victorian vampire stories, rely on the character's suspicion or ignorance of the vampire character's true identity. Like Polidori’s The Vampyre or Stoker's Dracula, the characters in Carmilla do not know the vampire is a vampire, and this adds a layer of suspense, a defining feature of Victorian gothic stories. Le Fanu was also interested in how the horror genre affected readers psychologically and this is evident by the way he plays with loneliness and gaslighting in Carmilla. |

Camilla Doherty | ||

| 1897 |

The Immortal Tale of DraculaDraft |

Stephanie Schlies | ||

| The start of the month Jan 1924 |

The Adventure of the Sussex VampireDRAFT “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” is a short story written by Arthur Conan Doyle and is one of the many stories following the famous Detective Sherlock Holmes. Originally published in the January 1924 edition of the Strand Magazine, this story follows Detective Holmes and his assistant Watson as they investigate a woman whose husband believes her to be a vampire. This is not unlike many of the other vampire stories of decades past, but one thing sticks out: the vampire in this story is not real. When reading through vampire stories of the 19th century, we find most of them focus on explaining the vampire as a monster and exploring different traits that a vampire might have. In Doyle’s story, however, it is assumed that the reader is already familiar with what a vampire is and can recognize the traits one may have. In stories like Carmilla or even Dracula, the idea of a vampire is very new to every character in the text. They learn along with the reader what a vampire is and how they come to be. In these stories, the idea of a vampire was still rather new, meaning most people reading truly would not have known what a vampire was, or at least, it was very likely that they wouldn’t know. For this reason, much of these stories take the time explaining the characteristics of the vampire and walking the reader through each abnormality. This changes throughout time though, so much so that by the time “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” was published in the 1920’s, it was expected that anyone reading would at least know that vampires are people who drink the blood of others. This insinuation of common knowledge helps us to understand just how substantial and societally influential the vampire was throughout the 19th century and brings to light the entire genre that it has created. Now, there are multiple shows, fanbases, movie franchises, and book series that center around different vampire tales. It has become its very own genre, a genre that “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” barely makes it into. In this story, unlike every other vampire story in the genre, the vampire is not real. This stands out in all the works we’ve read, as in every other, the vampire being discovered as real is the climax of the story. The formulaic writing of Aurthor Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series aids us in the early assumption that surely, there is no vampire, as his stories are always mysteries. In this, we are to assume that the mystery to be solved is what is really going on, since vampires are not real. This brings us to a question: what genres are vampires assumed to be real, and what genres are they assumed to not be real? I would speculate that in “realist” fiction, such as classic mysteries, we would assume that any character thought to be a vampire is not truly a vampire in that universe. However, in fantasy, horror, or even science fiction, it would not be a stretch to believe that any character presented to be a vampire truly is a vampire in that universe. This explosion of genre from the world of vampirism in fiction is exciting, intriguing, and most of all, to die for. |

Rose Tiedt | ||

| 1958 to 1974 |

Dracula (Hammer)Hammer Film Productions is a British film production company specializing in the horror genre. They’re most known for their works produced in and around the 60s, one of which being their series on Dracula. Beginning with Dracula in 1958 and ending with The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires in 1974, Hammer revitalized the character for the modern audience and then proceeded to milk that cash cow until the modern audience no longer cared. Though despite how it ended, Hammer Dracula was incredibly influential on the pieces of Vampire fiction following it. One notable feature with Hammer’s treatment of Dracula is how well they vilified him. Vampires since the beginning have often been established as tragic creatures. However, pieces featuring Dracula often treat him as an unsympathetic villain, something not started but definitely encouraged by Hammer. In these films, Dracula is a monster. He’s an entity where destroying him is treated as an objective good. This isn’t seen with many other stories considering how often vampires are romanticized. An important part to the establishment of Dracula’s evil in Hammer is his actor, Christopher Lee. The performance Lee gave the character showed how vile and nasty he saw the being. Compared to the suave, charismatic treatment given by some other famous portrayals, Lee performed Dracula as if he was a feral monster. And in many instances, he was. However, despite how the films treated it, Dracula’s evil was not immortal. There was a gradual decline in interest toward the series going alongside the gradual decrease in quality. Horror films in the early 70s were seen more as something to be on in the background while teens hung out rather than something to be viewed artistically. So less effort was put in to the dismay of horror enthusiasts and some actors. Lee was especially upset by this, mostly because he had to be in the movies. He wanted to retire his Dracula before it was subjugated to more terrible scripts, but was forced to stick with the role due to contractual obligation and guilt-tripping from the company. Hammer Horror is post the Victorian era, but it’s such an important part of vampire history that it can’t be looked over. The works that predate it have subtle influences toward the lore used and the setting the stories take place in. However, Hammer’s Dracula disregarded the need to be accurate to those stories, including the very book it is based on. They wanted to do their own thing and did so with a certain degree of success. Rather than just being the result of the previous vampire history, Hammer’s Dracula series pushed vampires forward into the next era. Hammer isn’t brought up often in conversation even when discussing horror media. When it comes to the “classic” monster movies, most look at the Universal films that come before it. However, even though conversation about it is lacking, Hammer has had an important influence on both the film industry and the horror genre. Hammer is something that cannot be forgotten. |

Zoom Coe | ||

| 9 Jul 2002 to 21 Dec 2005 |

Carmilla MagazineCarmilla was a series of lesbian/fashion magazines published in Japan from 2002-2005, with ten editions published in its entire run. The beginning of every volume includes an introduction which speaks to the reason why the editors (Ayako Saito, Meymi Inoue, Kyou Aoki, Hiromi Otsuki, and Yukiko Kawanishi as of volume one) chose to name their magazine after Le Fanu's nineteenth century vampire publication. Here is a full translation of the introduction: The later half of the nineteenth century saw the creation of one of the original vampire stories, Carmilla, by the hands of an English writer named Le Fanu. The story involves a woman with a wicked charm, Carmilla, and a heroine conflicted between her attraction and fear. It was, supposedly, many readers first time reading a romance story between women. The heroine of this story, a woman who never imagined she would be involved in a dramatic tale, finds herself being seduced into a whole new world by the titular vampiress. We named our magazine Carmilla with the hope that it will be just as alluring as its namesake. (Also, the term “vampire” has been used a lot in the past as a label for homosexuals who seduce innocent heterosexuals, so we felt a bit of a desire to reclaim the label.) Now then, what world will Carmilla, a woman who appears in the bedchambers of maidens, lead you to tonight? Right from the introduction, Carmilla makes it clear that this is a magazine that is interested in the bedroom. Carmilla covers a plethora of content and genres, including interviews, short stories, manga, short-form memoirs, photographs, shopping and fashion advice, and many kinds of educational materials--particularly those involved with explicit lesbian activities. It was similar to a literary journal in that Carmilla called on its audience to submit stories for publication. Some stories were even split up between multiple volumes, just like how Le Fanu's Carmilla was serialized.

The vampire theme typically wasn't mentioned in Carmilla apart from the introduction. The focus within volumes was instead on clubs, fashion, and sex--but I think plenty of parallels could be drawn. Vampires are typically depicted as outcasts, and in some myths, they physically cannot enter a space until they are explicitly allowed in. Members of the LGBTQ+ community can probably (and quite unfortunately) relate. Although marriage equality in Japan still has a long way to go (click here for a quick background on this topic), modern technology has given marginalized groups access to more resources. With that in mind, it makes sense that a lesbian-created magazine about lesbians published in the early 2000s has such a strong focus on sharing resources and education.

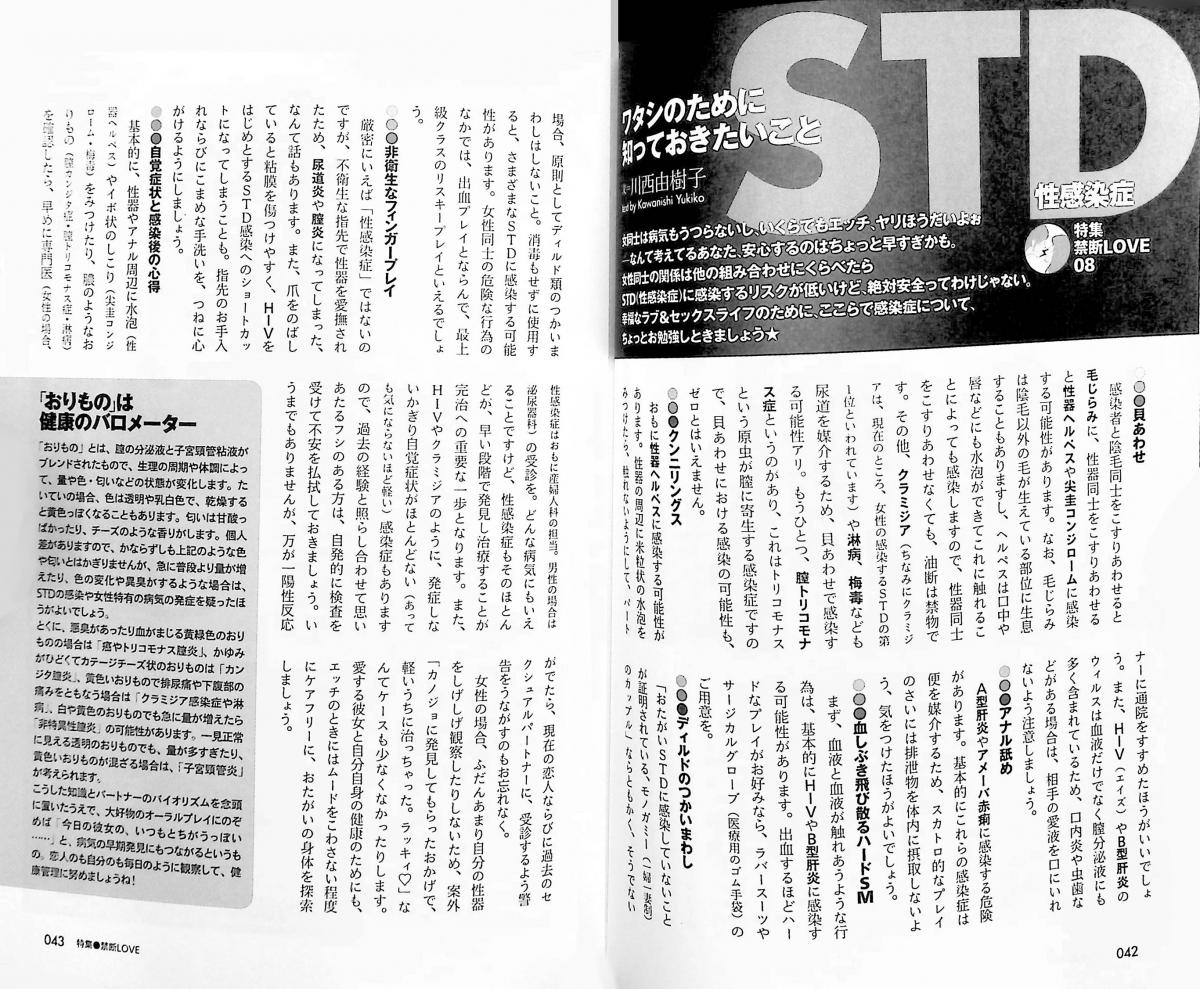

Volume three, for example, has a section about the risk of STDs and best practices to avoid them. The same volume also gives a list of lesbian-friendly bars, clothing advice for adult role-play, and even a bondage tutorial. What's most exciting about Carmilla is how every volume offers different content, making every volume feel like a valuable addition to the last. The first volume included a list of websites for people to meet other lesbians, the second volume featured several different lesbian-friendly clubs, the fourth volume had a kissing tutorial, and so on... I wonder if perhaps this has something to do with the surveys at the end of each volume, which were designed to be cut out and mailed back with feedback. This feedback survey was commonly included in many manga volumes that were printed around this time. Sometimes a giveaway item would be used as incentive to fill it out. (You can learn a little about them here, though I had a hard time finding many sources about this.) Perhaps the feedback form greatly encouraged the kind of content the editorial staff included in their next volume.

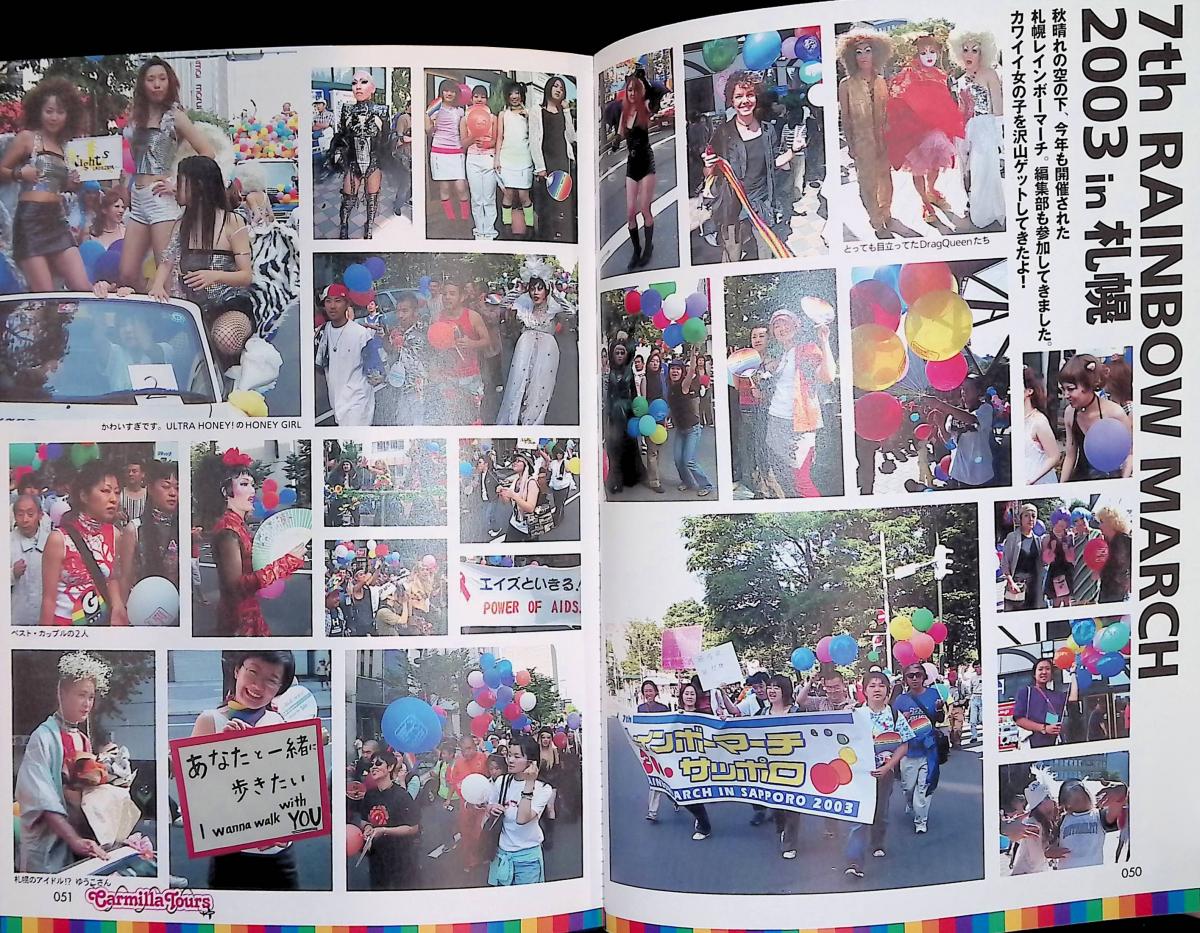

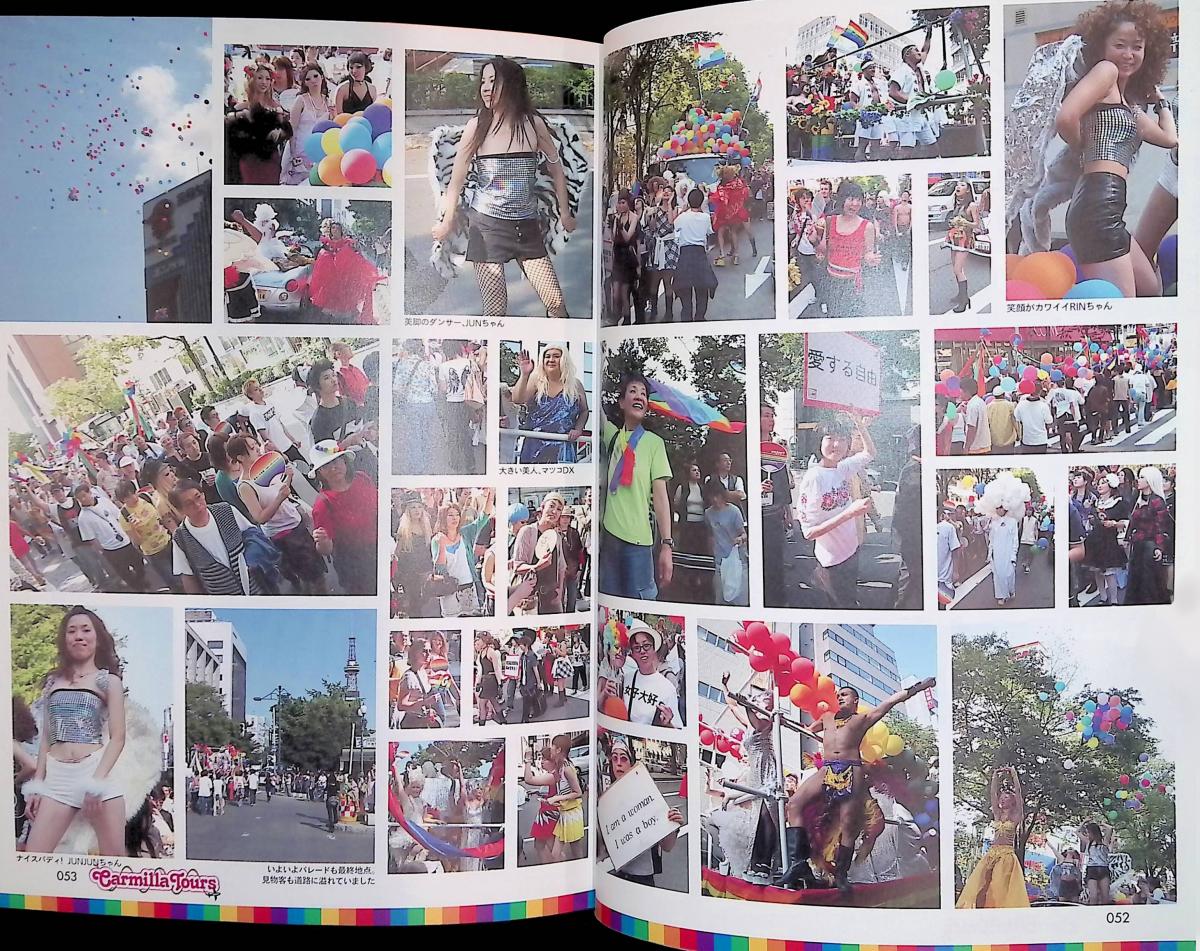

Perhaps my favorite part of these magazines so far have been the color photographs of the 7th Rainbow March in Sapporo, featured in the middle of volume three. The majority of these magazines are printed in black-and-white, so the splurge for a color center-spread is equally eye-catching and touching. The majority of Carmilla is targeted towards cisgender lesbians, but the photos they include in this section makes it clear that they wish to be inclusive--or understanding, at least--towards the rest of the LGBTQ+ community.

In Le Fanu's Carmilla, the titular character was always confident about her own identity. Unlike many other Victorian vampires, Carmilla didn't seem to despise her nature as an Un-Dead. She also never tried to hide her affections for the protagonist, Laura. "Her soft cheek was glowing against mine. 'Darling, darling,' she murmured, 'I live in you; and you would die for me. I love you so.'" (Le Fanu, Carmilla) Carmilla's pride hasn't just influenced Victorians; it has also influenced those of the 21st century, and that, I believe, is beautiful. |

Kimberly Rouse | ||

| 25 May 2013 to 11 Apr 2014 |

2013 - Only Lovers Left Alive FilmOnly Lovers Left Alive is a 2013 film directed by Jim Jarmusch, and starring actors Tom Hiddleson and Tilda Swinton as the vampires Adam and Eve, respectively. The film centers around the two vampire lovers reuniting after spending years, if not decades, apart, after Eve notices that Adam, her husband, has become more withdrawn than usual. Life as a vampire in the 21st century is hard, as pollution has taken a toll on the blood supply, leaving the vampires isolated and wanting for non-contaminated blood. Adam, being a creative soul, has spent his life and unlife influencing creators and inventors, as he is normally very brooding and withdrawn, while Eve is naturally much more outgoing and free spirited. She brings a bit more “liveliness” into his life for a bit before Eve’s sister, Ava, comes crashing back into their lives with her addictive personality and drinks all of their stash of good blood. After Ava also ends up killing someone at a club by drinking all of their blood, Adam and Eve end up fleeing back to Eve’s home with the last bit of good blood left, contemplating their unlives and their love. The film Only Lovers Left Alive is notable in terms of vampire media, for its depiction of a sympathetic vampire couple and the struggles they go through in their unlife. Adam’s long unlife and naturally very melancholic personality has left him struggling to find meaning in his life as it continues, something that is only balanced out by his wife, whose personality compliments and contrasts his personality perfectly. She is able to be that life and light he needs, and the distance has clearly, in part, left him struggling. Adam fits in with a lot of previous literature on vampires as he is very much a brooding, almost Byronic type, living an artistic life full of melancholy and listlessness as he tries to find purpose, something that he is only able to find fleetingly while he’s with Eve or working with someone else to inspire them to create. Eve, on the other hand, is more unique amongst vampires, especially those of the Victorian era, as she is full of life. She too spends her time around artists, but she clearly has more vivaciousness and excitement in her day to day when compared to her struggling artist husband. In the end, however, their lives are both turned upside down when Eve’s sister, Ava, who is a more classical representation of vampirism and it’s all consuming hunger and, sometimes, allegory for addiction, comes back into both of their lives. While Eve and Adam are not, themselves, destructive vampires, Only Lovers Left Alive does show that vampirism ultimately is self-destructive as Eve and Adam are left to contemplate their lives and what to do next once their blood supply is gone, leaning on each other to bring them love and comfort. While vampirism is destructive, it is the connections they make that bring them joy, something that is echoed when Adam takes interest in a new musician at the end of the film, giving the hope that, maybe, things will turn out for them. |

Trinity Cottrell |