Introduction

Omnibus Critical Edition of Christina Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio”

Dino Franco Felluga, A Momentous Edition

Kenneth Crowell, Sonnet: Genre and Intertext

Herbert F. Tucker, Sonnet: Structure and Inner Form

A Momentous Edition

Dino Franco Felluga

This edition of Christina Rossetti’s sonnet, “In an Artist’s Studio,” seeks to rethink how we approach edited work in a variety of ways:

Omnibus

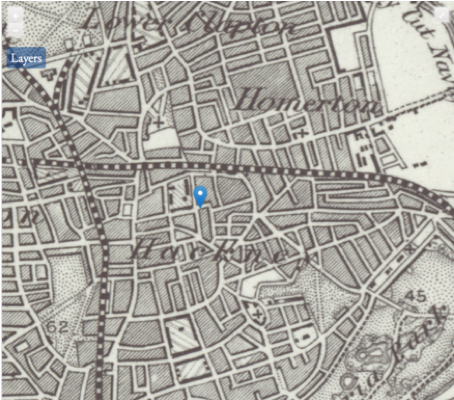

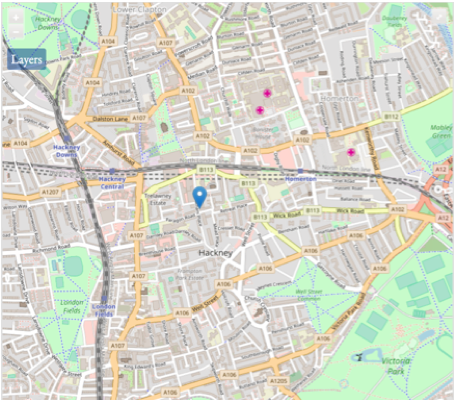

Like the earlier COVE publication of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “On a Portrait of Wordsworth,” edited by Dino Franco Felluga, Joshua King, Christopher Rovee and Marjorie Stone, this version of Christina Rossetti’s poem is an “omnibus edition” that brings together in one edition a variety of interconnected tools made available to scholars and students at The COVE: a multimedia annotation tool; a timeline; a geospatial map (including a historically accurate layer for the United Kingdom from an 1880s ordnance survey); and a gallery of images. Although this poem is much anthologized, no previous edition has been able so fully to bring together biographical information about Christina Rossetti, her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti (DGR) and her brother’s wife Elizabeth Siddal; as well as Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s many paintings for which Siddal and Christina Rossetti sat as models; and even precise geospatial information about places associated with the Rossettis. By linking these different tools, one can quickly gain a better understanding of the biographical and cultural background of this much-anthologized poem. For example, when looking at the carte de visite photograph of Elizabeth Siddal over which DGR painted in watercolor, one can scroll down to see the exact location where the photograph was taken (14 Chatham Place); one can zoom in to see what the place looked like in the 1880s (thanks to an ordnance map provided to COVE by the National Library of Scotland); and one can toggle off that map to see what that location looks like today (figs. 1 and 2).

Each individual geospatial place also has its own individual page (https://editions.covecollective.org/place/14-chatham-place, in this case), where one can go for more information.

Scroll down further on the gallery page of this carte de visite photograph and you can also see a timeline of events associated with Elizabeth Siddal and DGR. In addition, one can visit a yet more complete timeline and geospatial map, both of which are interlinked with our edition and with each other:

https://editions.covecollective.org/content/artists-studio-timeline

https://editions.covecollective.org/content/artists-studio-map

Each timeline event and each place have individual pages that can, in turn, be connected with each other, for example:

https://editions.covecollective.org/place/highgate-cemetary

https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/burial-elizabeth-siddal

The result is a cornucopia of information that can help scholars, students and the general public understand this rich poem better.

Momentous

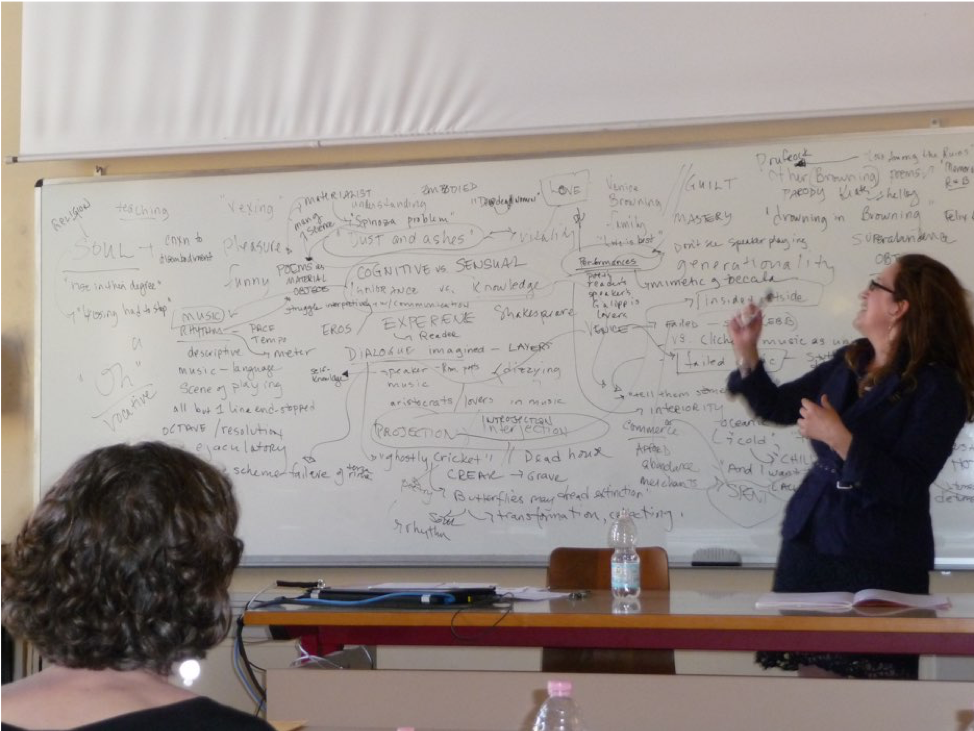

This edition was originally conceived as a way also to make more permanent the sorts of close-reading sessions that scholars occasionally run at conferences or amongst themselves. The idea was inspired by a close reading of Robert Browning’s “A Toccata of Galuppi’s” led by Cornelia Pearsall at the NAVSA/BAVS/AVSA conference that I organized with Emma Sdegno and Michela Vanon Alliata in Venice, Italy in June 2013 (fig. 3).

About 20 scholars discussed the poem intensely over the course of an hour, leading to a number of what I felt at the time were extraordinary insights. I was so taken by the discussion that I decided to add the poem to my syllabus the following semester; however, by the time I got to that class discussion in October I could no longer recall the details of our entire discussion. If not for the picture I took of our whiteboard (where Pearsall occasionally jotted down mnemonic scribblings; fig. 3), there would be no tangible record of our conversation at all.

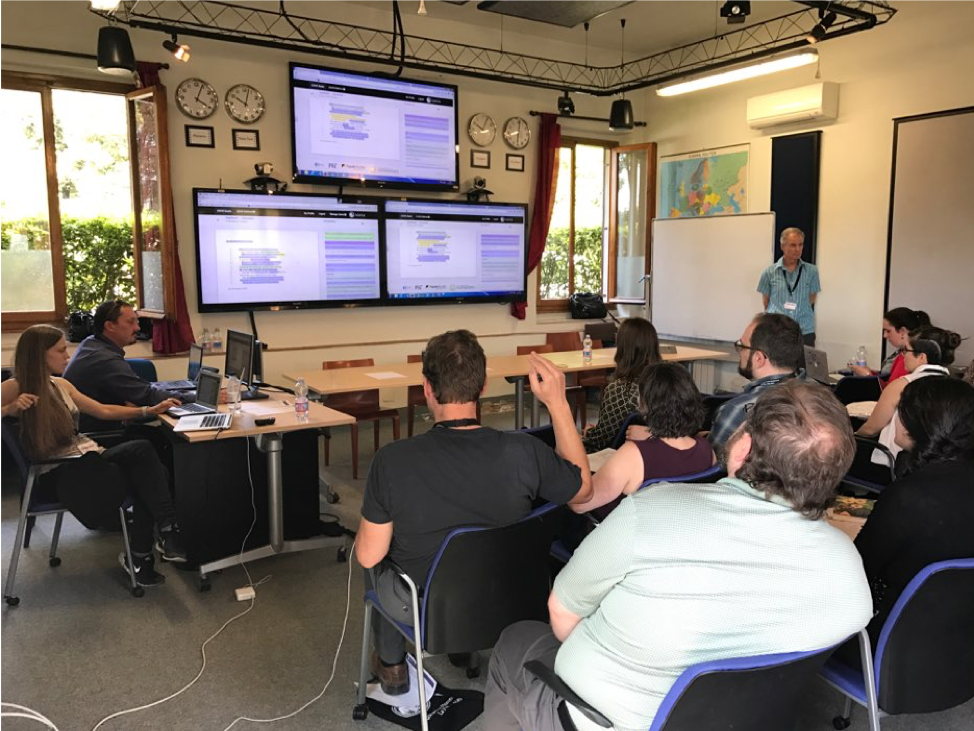

When Herbert F. Tucker and I ran a similar workshop at the Florence conference that I organized with Catherine Robson at La Pietra in 2017, we decided to use the COVE annotation tool to make our conversation a little more permanent. I originally intended for us to discuss DGR’s “A Sonnet is a moment’s monument,” in part because I wanted to borrow from that first line of the poem to describe what we were attempting: a “momentous edition,” the making permanent of an ephemeral, “momentary” conversation. We decided, in the end, to concentrate instead on C. Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio.” As our conversation proceeded, I was again struck by the wonderful insights of the 20 or so colleagues in the room. This time, unlike at Venice, The COVE’s two administrative directors at the time, Dominique Gracia and Kenneth Crowell (pictured on the left in fig. 4), were in attendance to serve as amanuenses, jotting down in COVE Studio who was saying what. As our conversation proceeded, attendees could see, with the help of computer projection, a live annotated edition forming before their eyes, as pictured in fig. 4.

Following this conversation, I invited participants to continue working on the edition with an eye to peer review and publication at The COVE. Pamela Buck, Kenneth Crowell, Nicole Fluhr, Dominique Gracia, and Melissa Merte decided to join me and Herbert Tucker in the effort. This edition of “In an Artist’s Studio” is the momentous result.

Collective

The final thing that distinguishes this edition is The COVE’s approach to humanist knowledge. Rather than hide our insights away in university libraries or behind commercial paywalls, The COVE seeks to make knowledge visible so that the general public has a more trustworthy place to go for scholarly work (unlike, say, the many, much less reliable editions of literature that one can find at genius.com). It also aims to make knowledge re-usable and collective. Once a timeline event or place description or image description is published at The COVE, it is made available to others for re-use. My earlier editorial project, BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History (itself a scholarly alternative to Wikipedia) has already been deracinated from its static location at branchcollective.org so that anyone using The COVE’s timeline tool can quickly draw from BRANCH content to form a custom timeline or map in minutes, as illustrated in the first video on our how-to page:

https://editions.covecollective.org/content/how

All map, timeline and gallery elements from current and future COVE publications will similarly be made available to others wishing to create their own timelines, maps and galleries. For our edition’s gallery, Jerome McGann has deracinated the content of his groundbreaking Rossetti Archive so that we could assemble that knowledge in our own gallery and then make these individual gallery descriptions available to future users, including students:

The goal here is to safeguard and share our cultural heritage while making our work more readily available to students and the general public.[1]

Sonnet: Genre and Intertext

Kenneth Crowell

Similar to our own collective approach with COVE, Christina Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” stands as an example—a mirrored reflection if you will—of the power of a collective approach to aesthetics, education, and the curation of a cultural heritage. If a “sonnet is a moment’s monument,” as Christina Rossetti’s elder brother Dante Gabriel asserted, it was certainly not an isolated moment. The sonnet as a form was not, as J.S. Mill would suggest, “feeling confessing itself to itself in moments of solitude.” Rather, the Victorian moment of the sonnet in British history (what one critic of the time dubbed “sonnetomania”) was a moment of collaborative writing and listening. From the Rossetti family’s early experiences with bouts-rimés sonnet writing contests—which provided the germ for The Germ, the short-lived journal vehicle of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s aesthetic philosophies—to the later proliferation of sonnet anthologies that profited upon the vogue for the form, the Victorian sonnet was engineered as public discourse.

Further, Victorian sonneteers were fully invested in dialogue and discourse with their sonneteering forebears. Not only did the Victorians build upon the extant tradition of their immediate and obvious Romantic influences—Charlotte Smith, William Lisle Bowles, Capel Lofft, and, of course, William Wordsworth who told us to “Scorn not the Sonnet”—but they also recognized a continuum between their efforts and those of John Milton, William Shakespeare, and Thomas Wyatt; and from these early English sonneteers to their Italian influencers: Francesco Berni, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti, Dante Alighieri, and, finally, Francesco Petrarca.

“In an Artist’s Studio” illustrates the collaborative and intertextual character of the Victorian sonnet. That the poem is ekphrastic is immediately evident. In our annotation of the poem, Dino Franco Felluga provides images of the Dante Gabriel Rossetti paintings that provide the bases for Christina Rossetti’s quick and ruthless exegesis of the reactive misogyny of the stunted male ego. But these paintings are enframed here in this studio not by their original Pre-Raphaelite gilding, perhaps in a room at the Royal Academy, but within a different room, a stanza built onto the sonnet tradition (“stanza” means room in Italian). To read “In an Artist’s Studio” is to read Christina Rossetti’s reading of a woman’s place—a room of one’s own, as it will come to be called by Virginia Woolf—within the Petrarchan blazon tradition. “In an Artist’s Studio” is the beginning of Christina Rossetti’s affirmation that, while the Petrarchan tradition might trap its Beatrices, Lauras, and innumerable “donne innominate,” “Sonnets [can be] Full of Love,” and protest, and resistance.

The multiple images of the unnamed woman that the poet-speaker of “In an Artist’s Studio” encounters reflect the repetition compulsion of a painter “feeding” upon his subject. However, they also prefigure Rossetti’s statement in the introduction to her later “sonnet of sonnets,” Monna Innominata, that the women whose images have been trapped in poetic series by sonneteers from the time of Petrarch have “paid the exceptional penalty of exceptional honour, and have come down to us resplendent with charms, but (at least, to my apprehension) scant of attractiveness.” Hinting at why her “artist” has an insatiable, vampiric desire for multiplicity of female representation, Rossetti suggests that, evacuated of agency, evacuated of all but her image of unattainability that is then anatomized over and again, Beatrice, Laura, innumerable donne innominate after them, and finally, Elizabeth Siddal, lose their selves: lose the power to say “here I am; I exist.” “In an Artist’s Studio” places Dante Gabriel’s work, but also Christina’s own sonnet writing, firmly within the tradition of a Petrarchanism whose impulse towards serial production of its women is instigated by the diminishing returns of a predatory male desire that is in constant pursuit because it constantly effaces the women it pursues.

“In an Artist’s Studio” tasks the reader, then, with interrogating the collective Victorian moment of the sonnet, which in its turn back to Renaissance, and indeed pre-Renaissance, Pre-Raphaelite models, attempts to reclaim Petrarchanism as a mode for nineteenth-century aesthetics. She asks us to question why Elizabeth Siddal cannot speak for herself but must only be seen, over, and over, and over, as a projection of a male desire that Rossetti figures as itself trapped by the social and literary forms by which it seeks to liberated expression.

Reading “In an Artist’s Studio” means reading into an 800-year-old tradition: a tradition that silenced female voices while at the same time preserving their images for posterity, but a tradition that was also taken up readily by female poets—indeed which was in large part resuscitated by female poets in the Romantic period, as Stuart Curran argues in “The ‘I’ Altered.” “In an Artist’s Studio” acknowledges the debt of Victorian sonneteers to a fraught Petrarchan tradition but also identifies within the history of the sonnet a coterie tradition from which, Christina Rossetti suggests, we could reclaim a collective, empowering, feminist poetics. We might argue that COVE’s approach to interpretation does just this, using the very logic of the blazon—segmentation, anatomization, overdetermination—collectively to reanimate and make whole the mirrored, surface sameness of feminine representation within the Petrarchan tradition.

Melissa Merte, for instance, pays close attention to how Christina Rossetti’s lone use of the first-person plural pronoun “We” could possibly implicate us as readers in the voyeurism necessarily involved in the blazon tradition, while Pamela Buck augments this reading by suggesting not only that the “artist” in the painting seems sexually predatory but also that this nature mirrors the predatory practices of art in general: years, youth, beauty, and identity are all sacrificed by women for the successes of the male artist. Dominique Gracia also pays very close attention to the seemingly insignificant aspects of language—in this case the indefinite article “an”—to argue that the compulsions evidenced by the “artist’s” art are generalizable, endemic to the practice of representing the female subject, and Nicole Fluhr asserts the extent to which Rossetti’s poem resists the anatomizing male gaze of the blazon tradition. I highlight the poem’s anaphora as a technique recalling the repetition compulsion of both sonnet series and repeated visual studies of the female form, while Dino Franco Felluga provides us with images of the Dante Gabriel paintings to which Christina was referring. In total, then, this COVE “momentous edition” collectively activates and animates Christina Rossetti’s already multimedia poem to examine and contextualize the moment of the Victorian sonnet.

Sonnet: Structure and Inner Form

Herbert F. Tucker

Rossetti shares with the reader of her sonnet a mischievous version of the problem that faces the reader of the canvases at its center: namely, the interpretive problem that arises when a work of art poses no evident challenge to interpretation. These paintings have nothing to hide, no contrast engendering variety of a more than superficially trivial kind. “One face looks out,” “One selfsame figure” renders “The same one meaning” – it’s all one with this stuff, which forecloses even the latency of reserve, since “all” the “loveliness” of the pin-up figure gets faithfully captured in a mirroring reflection, and the uniform meaning comes in a fixed, one-size-fits-all quantity, “neither more nor less,” take it or leave it. If no more than this were at stake, of course, we wouldn’t favor this sonnet with a second look. Well, then, does the poem have something to hide? Once we suppose so, we are rewarded with dividends of some complexity – but only after the poem has dallied with the likelihood, well known to footsore gallery-goers, that there’s really not that much here to see. For the job of this as of many an ekphrastic poem is to make the shortcomings of visual art lead to literary art’s long suit: temporality. As Lessing had said a century earlier, poetry unlike painting unfolds in time and therefore may change. In the century after Rossetti’s, Wallace Stevens would go further and say it has to.

Rossetti’s certainly does. Suitably for a poem about paintings, one way she plies the formal sonnet structure is to shift the frame of reference – changing not the unchanging portraits themselves but how they are apprehended – in each of the sections the rhyme scheme delineates. Lines 1-4 sketch the studio named by the title: the “canvases,” “screens,” and “mirror” stand in for all the artisanal bric-a-brac that exhibited paintings put out of sight and out of mind, yet that all paintings arise in the messy midst of. Supplies, equipment, the consumer-shy debris of the shop are thriftily acknowledged in this opening quatrain to propose that technique is one of the places to look if you want to get past the homogeneity of surface display; and it’s a nice touch on Rossetti’s part that each of the objects we just noted in the opening lines is itself a surface. The second quatrain, executing the same abba rhymes as the first, deserts the means of production in favor of the produced art commodity, available in five flavors so clearly equivalent that for the last two all descriptors can be dispensed with (who doesn’t know what saints and angels look like?), so as to leave room for a resumption of that uniformity problem with which we began: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

With the sestet’s departure into fresh rhymes freshly arranged (cdcdcd), the frame of reference changes again – twice, in fact, since as we’ll see Rossetti summons in closing something like the final coupleted switch of the Shakespearean form that she seldom embraced in form but could not, being an English poet, help bearing in mind. After the volta, lines 9-12 turn a corner that clinches a frame around the aesthetic display of contents we just visited in lines 5-8. Backing out of the figured world of pictorial representation, we behold a different register of production, this one not artisanal but psycho-pathological. The painter who oddly hasn’t been around his own studio for eight lines materializes here, in a trance of narcissistic regard that explains why he has been missing in action thus far. His entire life is devotedly absorbed in Pygmalian co-dependency with the work of his hands, along an addictive feedback loop whereby an insatiable need produces an answering art that comes to only so much life as will gratify that need until it arises again and craves serial replenishment in the next, interchangeable canvas. “True, kind,” “Fair,” “joyful,” “sorrow”-proof, unfailingly patient and nourishing: these modifiers depict the ideal Victorian woman, we reflect, until we reflect a little further and see that a Victorian ideal is all that, within this artist’s studiously idealizing practice, such a painted woman can ever be.

Some such reflective ripple, on the stymied interpreter’s part, it becomes the business of the last two lines (with their distinctly slanted d rhyme at the close) to induce. The two “nots” of line 12 have executed a kind of police action to clear art’s precinct of trouble-makers like “waiting” and “sorrow,” impatience and pain. But then lines 13 and 14, while repeating the syntax of ritual negation, use it for the counter-magical purpose of smuggling reality into the picture – not the painter’s picture now, but the poet’s. The latter picture attests new knowledge of two kinds, one per line. The poet has knowledge not of the ideal woman but of the real one, affirming her (twice) “as she is” in actual space and time. Time first, opening out the temporal dimension where “is” differs from “was” and we are all of us – painters, posers, consumers – men and women with a past. Then space: no longer the illusory space of a timeless aesthetic ideal, but the mental space that affords such illusion to begin with, and that is available for lease (like the studio?) at the cost of a life: the artist’s, the model’s, or both. Where the poet’s purchase on the real comes from, here at the eleventh hour, the sonnet doesn’t so much say as hide. Take a look back up at line 3, the strangest in the poem, to find the one piece of furniture that was omitted from our studio inventory above: “her hidden just behind those screens.” Cherchez la femme – she’s just over there. But where is that? Behind what “screens”? Memories? Fantasies of femininity, be they obsessively idiosyncratic or mythically shared? Finished canvases that the sonnet has taught us to see through, peering into a literary depth beyond pictorial representation? Or canvases stretched and blank (wan with waiting?), pending what novelties may emerge from the compromised yet undetermined potential of that imaginative realm we enter whenever we go “In an Artist’s Studio”?

[1] Dino Franco Felluga discusses the goals of The COVE more fully in “The Eventuality of the Digital,” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 21, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/ntn.742. See also Felluga and David Rettenmaier, “Can Victorian Studies Reclaim the Means of Production? Saving the (Digital) Humanities,” in the Journal of Victorian Studies 24.3 (July 2019): 331-43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcz027.