I came to COVE for multiple reasons but being technologically savvy was not one of them. While I had always used the online course management systems that my university provided, I didn’t do so in innovative ways. I posted assignments, and I had students post responses to excerpts. In other words, I used the online course management systems in ways that saved my students and myself a few paper copies, not in ways that intellectually enhanced our classroom experience. Seeing innovative projects like those found on NINES (Nineteenth-Century Scholarship Online) and on Wikipedia, especially projects addressing gender and race imbalances, made me envious of those with technological know-how. I was wrong.

COVE was exactly the place for me—and I would encourage anyone who experiences trepidation about technology to enter this world, because its tools are truly easy to use. Clear step-by-step videos gave me a sense of what I could create; thorough instructions within the system itself made the creation of timelines and maps smooth and even fun; the annotation tool, in truth, demanded no instructions for use, and a responsive COVE team, who answers queries quickly and plainly, provided the support I needed when a few questions, mainly about getting students access to the system, arose.

COVE, however, is not just a particularly welcoming entry-level digital pedagogy platform with a broad suite of tools; it is also designed especially well to address goals common to many nineteenth-century British literature courses. COVE allowed me—in the words of my courses’ learning objectives—to guide students (1) to consider Victorian fiction within its historical, geographical, and cultural contexts; (2) to analyze the aesthetic and cultural significance of the ideas, values, conventions, forms, and genres found in British Romantic, Victorian, and Modern literature; and (3) to synthesize their readings of literature with the readings of others.

COVE’s timeline and mapping tools and its annotation tool became invaluable in a junior/senior level class focused on Victorian gender issues and a lower division survey class, respectively. The following explains how these tools enhanced my pedagogical goals.

SEQUENCING AND MAPPING THE ROAD TO SUFFRAGE IN AN UPPER DIVISION VICTORIANS COURSE

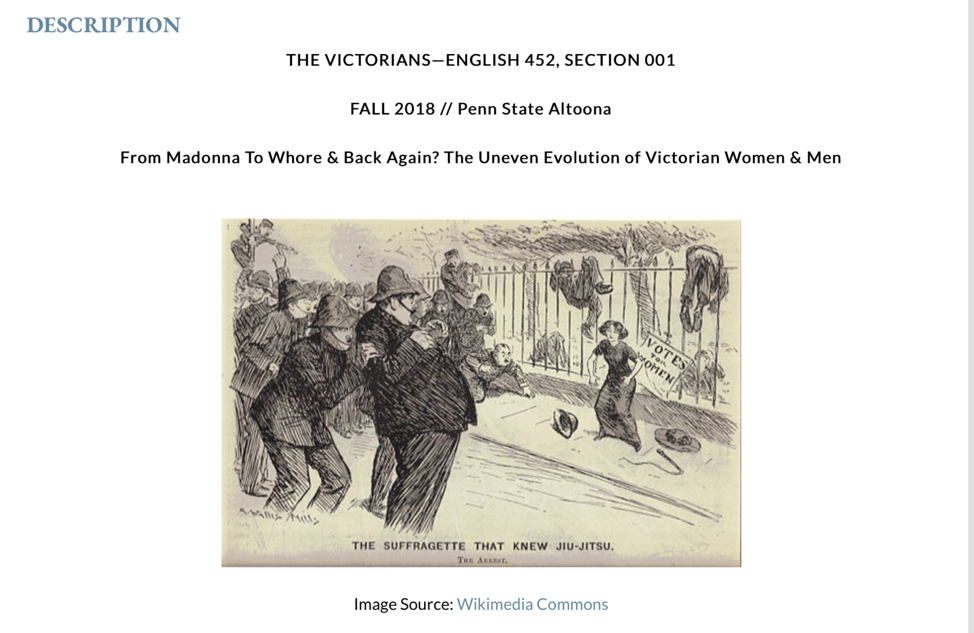

The first class in which I used COVE was a 400-level course on the Victorians that I subtitled “From Madonna to Whore and Back Again? The Uneven Evolution of Victorian Women and Men” (Fig. 1). I designed this course so that students could evaluate what led British women and men to the female suffrage movement. COVE’s timeline tool made it so that my students could engage with events described in the fiction and poetry we read. The timeline was not just an easier or flashier way to provide students necessary historical context. It led us all to examine the connections between the events. Such consideration informed discussions of the fiction, which in turn probed, with specificity, how the texts critiqued, for instance, women’s marital and monetary rights.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

I created “The Road To Women’s Suffrage” timeline (https://editions.covecollective.org/course/victorians-penn-state-altoona) by using materials already found on COVE. The process was easy, in large part because of the easy-for-non-tech-savvy-people-to-understand COVE instructional videos. When working on my timeline, I searched topics connected to women’s rights, then it was as simple as clicking those entries and hitting save. I followed that up by constructing an accompanying map of places linked with those events. I wanted the map so that students might identify centers of emancipation activity, most often in London, and explore their historical and social importance.

The ease of the process allowed me to focus on the assignments that I wanted to create on the basis of the COVE materials, not on technology. Those assignments also owe much to the inspiration provided by Dino Felluga in our email conversations and his discussion of his COVE class in “Teaching Time” (https://editions.covecollective.org/teaching/teaching-time).

My Victorians course had an enrollment of only ten. This size allowed me freedom to experiment and to create a timeline and map that were substantial without being overwhelming.

Evaluating Timeline and Map Entries

I created scaffolded assignments, first assigning students each a timeline event about which they were to become expert. These events all included links to multiple BRANCH articles. The goal was that students would synthesize the articles and discuss, in oral presentations and writings, how this information lent context to and complicated our fiction.

With this assignment, I targeted students’ difficulty in engaging with historical and literary scholarship. The BRANCH articles were particularly helpful in this respect. They are written for a general reader yet offer incisive scholarly readings. While COVE and the BRANCH articles did not totally alleviate my students’ difficulties when engaging with scholarship, they made a significant difference.

The novelty of the format in which the material was presented had more than a superficial effect. My students and their work were energized. They developed a sense of ownership of their assigned events.

They also, literally on COVE and quickly in class presentations, saw ideological connections between their events. That energy transferred to discussions of the fiction and poetry we read. The students who read about the Act on the Custody of Infants and the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, for instance, were particularly vocal when we looked at Helen and Arthur Huntingdon’s marriage in Anne Brontë’s Tenant of Wildfell Hall. We also had learned enough about the guiding ideologies of L. T. Meade and Alicia A. Leith’s Atalanta to debate how and if Edith Nesbit’s “The Girton Girl,” published in that journal, supports physically and mentally strong women.

I also asked students to be aware of the type of content and style of writing used in the timeline events and map sites. Because they would be creating timeline events and map sites themselves, I wanted them to become familiar with the “genre” of these COVE elements. We then discussed whether that genre worked for our purposes, a discussion that led to slight modifications for our needs.

We saw a need for a paragraph that gave readers a thumbnail description of what they would find in the articles that my students would include in their timeline entries. This addition created bulkier entries that are admittedly neither ideal nor typical timeline entries; however, my goal was to strive for significant engagement with the articles the students used in their research.

Creating Timeline and Map Entries

The next step was the creation of their events. Ideally, I would have had the students choose events to place on this timeline. However, I did not feel that I could give them sufficient instruction to lead to consistently productive choices. I thus assigned each student a topic about which to create a timeline event and an accompanying map site. These topics included, among others, the Women’s Social and Political Union, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, British women’s entry into higher education, and the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League.

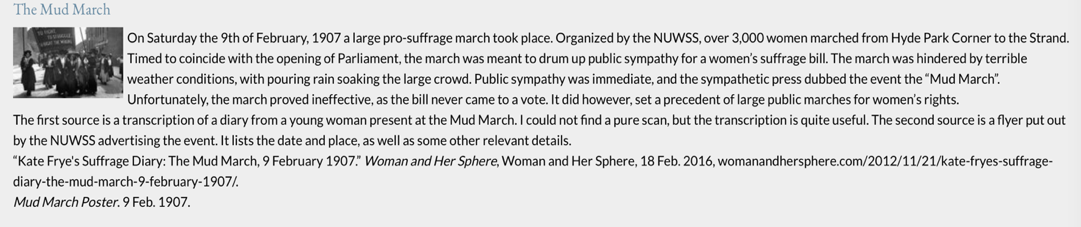

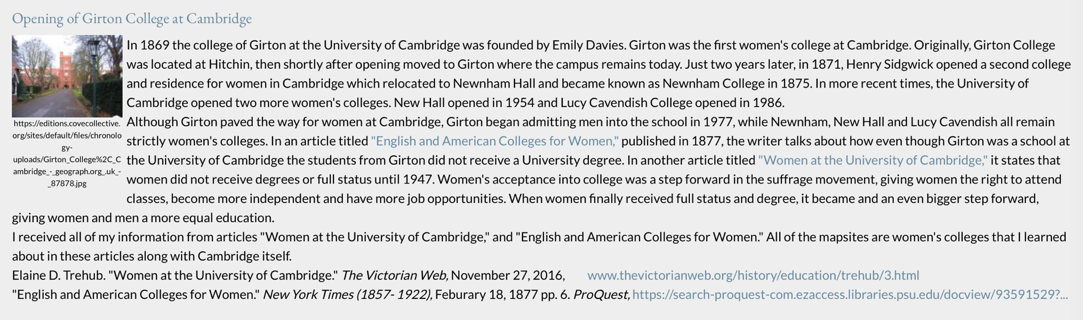

I gave the students the task of creating at least one or up to four timeline events on the basis of their topic. This led the student assigned the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), for example, to create separate entries for Millicent Fawcett (her birth serving as the event), the founding of the NUWSS itself, and the Mud March, one of the NUWSS’s most famous marches named for the inclement weather that the women braved. The student working with women in higher education broke her topic into the opening of Girton College, Cambridge and the establishment of the Association for the Education of Women at Oxford (Figs. 2 & 3).

These students’ accompanying map sites yielded meaningful results. The NUWSS-focused student learned that the Mud Marchers chose their route so that they would be seen by many, including some of the most powerful people in London. The student focused on Girton, because she searched the locations of multiple male and female colleges, and saw how the women’s colleges were often located quite far way from the “heart” of Oxbridge.

Figs. 2 & 3—Mud March event composed by Elijah Boyd-Plamondon & Girton event by Devin Poplin

Figs. 2 & 3—Mud March event composed by Elijah Boyd-Plamondon & Girton event by Devin Poplin

Sequencing and Mapping Outcomes

My students were challenged and invigorated by this assignment’s multiple requirements of them. Again, the sense of ownership of their timeline event topic helped immensely. There was also an appeal to the fact that a typical research paper was not the end result of this work. (They did compose another semi-substantial paper that required them to use their timeline event to engage with one of our novels, short stories, or poems.)

The pedagogical appeal was that this assignment’s requirements developed the skills that I was attempting to strengthen in these English students. First and foremost, they had to become experts on their topic. Instead of regurgitating information, however, they had to evaluate and then prioritize it so that they could create logical timeline events. The next step was a compact concise discussion of their event, and that required synthesis of a hefty amount of reading.

They then moved to the process of choosing the supplementary information to offer timeline-event readers. I required at least one picture, a connected map site, and at least two articles. For the articles, we decided that a short paragraph guiding readers through them was necessary. This “guiding paragraph” was another method by which to heighten the students’ engagement with and ability to distill scholarly writings. This work was the most challenging for the students; however, because they had prioritized and synthesized historical facts for their timeline event, those skills were more honed than those of prior students whom I had asked to undertake similar syntheses of scholarly articles.

I also asked students to give presentations about their timeline events that offered some background about the event but also focused on their selection processes. I was implicitly asking the students to discuss the range of materials found in their research and why some didn’t make the cut. I hoped to learn about their prioritizing criteria and audience awareness. Those ideas did surface to some degree. The next time I work with this assignment, I will formulate questions designed to target that information, in particular.

An unexpected result of the timeline-event creation and corollary presentations was the lively class discussions that ensued. At the point in the semester when the students gave these presentations, we were finishing Gertrude Colmore’s Suffragette Sally. This novel does a fine job of presenting different ideologies that impelled people either to support or oppose women’s suffrage. Multiple students for their timeline topics had been assigned suffrage groups. Others had researched people and events that spoke to whether and how women’s political and social participation should develop. All students were thus eager to compare and contrast the ideas of “their” person or group with that of other students. They also started comparing and contrasting Victorian women’s roles in politics with what we saw in the news. We found ourselves discussing the complexities of the reforms that Victorians called for and exploring the nuances in arguments for and against female suffrage. These discussions in turn helped us to engage current politics with more carefully critical eyes.

FROM ANNOTATIONS TO SCHOLARLY INTERACTION IN A LOWER LEVEL BRITISH LITERATURE SURVEY COURSE

The second course in which I used COVE was a British survey course that opens in Romanticism and moves through British Modernism (Fig. 4). As with my Victorians course, this class had a small enrollment, just fifteen. The annotation assignment that I created for this class could flourish with larger enrollments, however, because it thrives on active and frequent student entry into literary discussions. I designed it specifically to improve students’ close reading skills and to lead them into scholarly discussions in which they evaluate their own and others’ readings, perhaps thereby revising and/or enhancing their own.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

My inspiration for and ability to carry out my COVE hopes in this class came largely from Ken Crowell. His article “Access and Equity: Annotation as Translation with COVE Annotation Studio” (https://editions.covecollective.org/teaching/access-and-equity-annotation-translation-cove-annotation-studio) made me aware of the possibility of supplying students with almost all of their required readings through COVE. This meant students paid only ten dollars, whereas previous students had purchased an expensive anthology and novel.

Crowell’s article also introduced me to the annotation feature of COVE Studio. The annotation feature relies on texts being entered into COVE Studio. Because Ken Crowell, his team, and all of the COVE facilitators are extremely gracious, my students and I were supplied with over sixty poems, one short story, two prose pieces, two plays, and two novels (one a triple-decker) http://studio.covecollective.org/documents?docs=assigned&group=psu_a_2019_brit_survey (the link takes you to our readings if you are logged in to COVE Studio and have added psu_a_2019_brit_survey to your list of editions in your profile). I supplied the minimal number of other required texts through my university’s online course management system.

If my COVE use ended here for this survey class, I believe my students would have been satisfied. It was not the end.

Content, Craft, and Collaboration: The Annotation Requirements

In this course, I had students offer annotations six times throughout the semester, beginning with our Romantic readings and carrying through to the term’s end. Students annotated two works that I selected for each period we covered. They were required to post one annotation that was “content”-focused and one “craft”-focused for each text considered.

In the content annotations, I asked them to look up words or terms (people, events, etc.) with which they were not familiar and/or that they thought were significant to the text. Our first discussion of the “content” annotations gave me the opportunity to introduce students to the Oxford English Dictionary, accessible through our library’s database collection. There was true interest in the OED’s focus on word evolution. Some students discussed whether the word on which they focused was used in a contemporary or archaic manner.

The craft annotations required them to identify the literary techniques at work in the texts and to explain how those techniques added to the texts’ ideas.

I asked all students to read each other’s annotations after posting their own. They then composed in-class writings, responding to questions I crafted to yield comparisons and contrasts between other students’ and their own annotations.

These annotations happened only six times throughout the semester; however, I do not exaggerate when I assert that this work influenced almost all of my objectives for the class. It led students to become explicitly aware of what it means to analyze the aesthetic and cultural significance of the ideas in and formal shaping of literary texts. COVE’s controlled and comfortable environment made presenting and then evaluating their own critical readings in relationship to those of fellow students less daunting. That work translated into more engaged and focused class discussions. It also improved their ability to evaluate scholarly articles.

Content Cues

Some of the words that students looked up for the content annotations surprised me, at first. Some surprises arose because they investigated words that I thought common. Students, for instance, examined “impels,” “hermit,” “corporeal,” and “perchance” in our annotation of William Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” (101, 22, 44, 112). I feared they were picking words randomly. I was wrong.

First, I recognized that even my well-read students’ vocabularies are still growing. Second, I acknowledged that some of the words with which I am familiar because of teaching these texts often are not in everyday use. More importantly, these “surprise” words were sometimes used in innovative ways and/or placed at pivotal points within the lines. For example, “impels” stands at the end of an enjambed line, a point that led the student to recognize its force in moving the reader even more quickly to the next line.

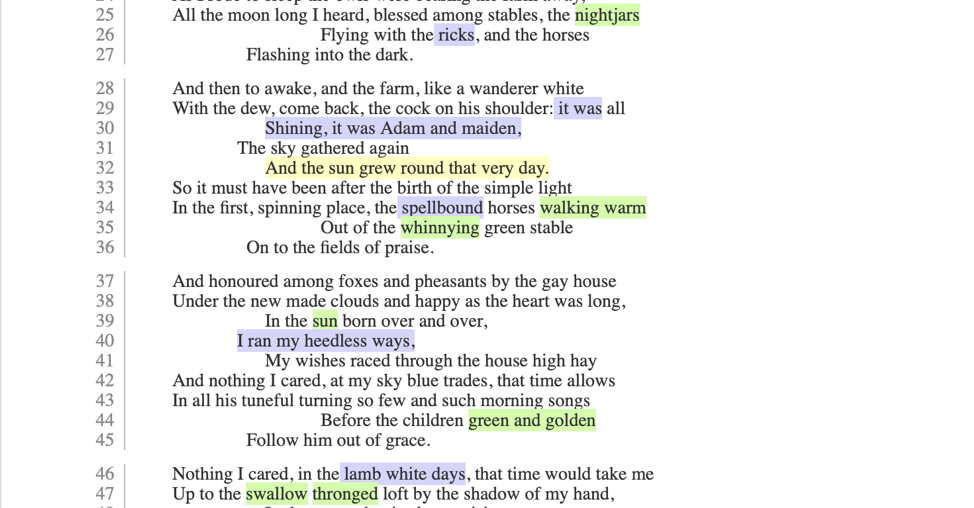

There were also surprises of another kind. Students would select words that I had read over. In Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill,” for example, two students focused on bird references, specifically “nightjars” and “swallows” (Thomas 25, 47). Their definitions and discussions showed how these birds lent to the mythical/mystical-realistic conflict felt by the students throughout this poem. (The nightjars take on a mythic quality because of the story of them suckling goats, ultimately making the goats cease to give milk. On the other hand, the swallows are a common and abundant bird worldwide.) The majority of both the content and craft annotations in that twenty-two-line section were focused on that conflict (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

One of my teaching techniques was also guided by these annotations. As the content annotations gave me insight into the breadth of the students’ vocabularies, I was better able to gauge how much “glossing” of poems—offering definitions of words with which I think students may not be familiar—I should do when reading poems aloud in class. It also inspired me to turn the glossing responsibility over to them at points and/or to ask whether students had looked up a word that I knew not to be common knowledge.

As students became more familiar with the annotation assignment, they did look up words more regularly. One student prefaced her discussion of a line of poetry not assigned for an annotation with “when I annotated it for myself, I found X meant . . .“ That remark solidified my belief in the value of having students annotate the readings. It moved me to decide that, when I use annotations in future, I will offer students the opportunity to post an annotation for at least one word for each class period. The benefits for both of us can’t fail to manifest themselves.

Crafting Insights

The craft annotations yielded similar results for my instruction and students’ class preparation. Students’ unclear or inaccurate uses of literary terminology, like “enjambment” or “caesura,” alerted me to concepts to revisit. The annotations also reflected the literary techniques that were clearest to and most powerful for the students.

Repetition carried such power, for example. Students’ keenness to find connections and echoes yielded some strong insights, especially into texts’ themes. Their focus on repetition also led to the students’ much greater willingness to believe in the purposefulness of writers’ word choices.

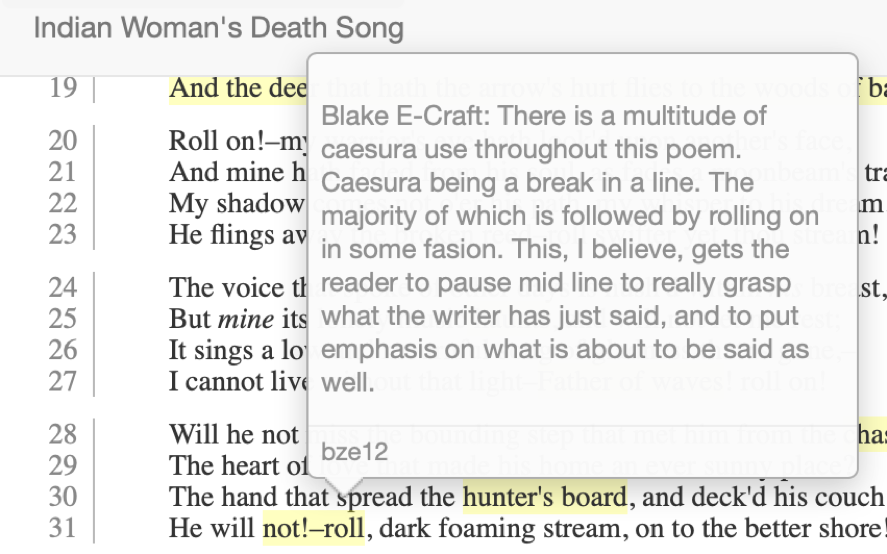

Caesuras’ power also emerged as a fecund focus. One student read this line of Felicia Hemans’s “Indian Woman’s Death Song”: “He will not!—roll, dark foaming stream, on to the better shore!” (31) as not only powerful in its exclamation-dash-created caesura, but reflective of the frequent caesura use throughout the poem. As Figure 6 shows, he argued that caesuras are consistently used before references to rolling/moving away from the constrictive life the Indian Woman led.

Fig. 6—annotation by Blake Evans

Fig. 6—annotation by Blake Evans

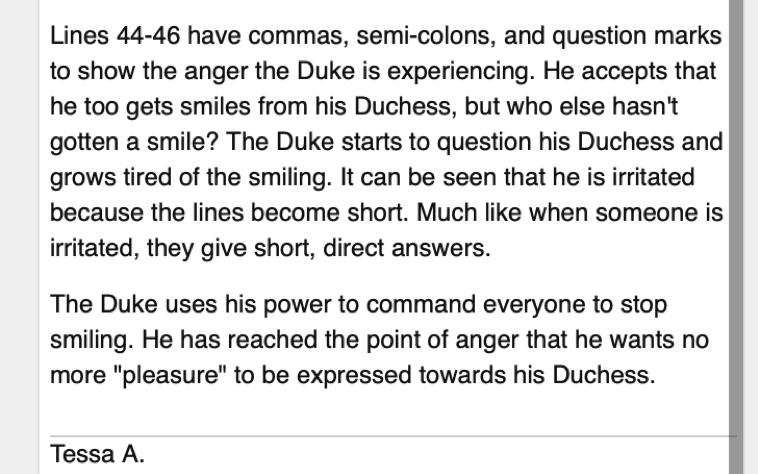

Some of the caesura readings also took into account the type of punctuation used. Another student, when reading Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” focused on Duke Ferrara’s lines:

. . . she smiled, no doubt,

Whenever I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. . . (Browning 44-46)

She discussed the different effects of the commas, semi-colons, and question mark—effects that, she claimed, combined to showcase the Duke’s irritation and anger (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7—annotation by Tessa Albert

Fig. 7—annotation by Tessa Albert

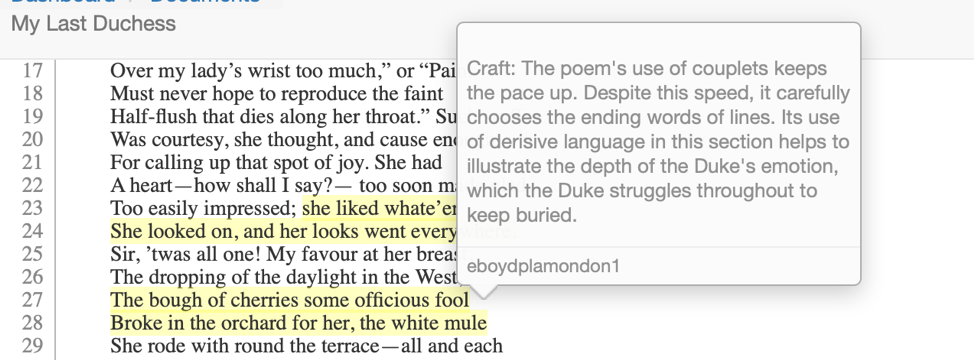

Rhyme was not a favorite. However, when students attempted rhyme-focused readings, the results were strong, as in another student’s reading of Robert Browning’s incensed Duke. Spotting the “fool”-“mule” rhyme, this student captured how the poem uses its couplet-driven speed to suggest the Duke’s barely contained fury (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8—annotation by Elijah Boyd-Plamondon

Fig. 8—annotation by Elijah Boyd-Plamondon

When using the annotation assignment with novels, I became powerfully aware of how this work could strengthen students’ reading of footnoted texts. The texts placed in COVE Studio for my class do not include footnotes. Students, however, often annotated sections that were footnoted in the editions of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway that I typically used. Tellingly, their annotations started with comments like “I totally misread this section until I looked up . . . ” In prior classes, I had found that supplied footnotes were not consistently read. With that in mind, I made a point to mention that the sections they chose were those often footnoted in editions of these novels. My hope is that when these students see footnotes in the future they come to them with a heightened appreciation.

Annotation Outcomes

This annotation assignment led my students to become exponentially more willing, even eager, to speak about specific lines of poetry and prose. In class, I always displayed the text under consideration on the front screen. That display invited students to consistently direct our discussion to lines by line number (all line numbers are indicated in the texts from the COVE text archive) or by phrases.

This engagement with the projected text also meant the students were looking up rather than hiding behind books. Admittedly, students also had devices on which to see the texts, and they could hide behind even the smallest of screens. And yet, more often than not, those personal devices were used to locate specific lines that they then would point out to the class by reference to the front screen.

Later than I would like to admit, I also recognized that I could use the annotation feature. Some of my uses were strictly utilitarian, such as marking sections of a novel about which I had constructed a question for the next class period. Other times I added links to images, for instance, of the Elgin Marbles and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting of “The Blessed Damozel," or audio recordings, such as Dylan Thomas’s reading of “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.” My goal is to expand on my use of the tool without becoming an intrusive presence in this rich canvas on which students direct our class discussions and guide me to becoming a more effective instructor.

Beyond the modifications noted above, I want to attempt in-class annotation sessions, as Joshua King describes in his “The Echoing Cry” (https://editions.covecollective.org/sites/default/files/The%20Echoing%20Cry.pdf). I will also have students annotate texts in groups, as Ken Crowell did in his survey course. I see both of these uses of the COVE annotation tool as catalysts to stronger annotations in terms of content and collaboration.

When undertaking King’s and Crowell’s assignments, students cannot fail to interact with each other’s ideas. They would also do so in a more face-to-face venue than what I created with the in-class writings. These uses of the annotation tool could further allow for more extensive work than I have yet had students do. They could also lead to more focused work, in that I could, as did Joshua King, offer specific lines of inquiry into the texts annotated.

A COVE CONVERT

When I entered COVE, I was curious yet lacking confidence in my ability to use digital pedagogy in a meaningful way. I have no background in even website development, much less the exciting work of the digital humanities. So, when I began, I feared and focused on the technology side of this undertaking. In truth, those fears almost stopped me from beginning. Moreover, even after I discovered that COVE was easy to use to set up assignments, I worried that teaching my students to use it would detract from class time. A good number of my students admitted to sharing similar trepidations when I introduced how we would use COVE in class. They too felt, initially, too unskilled in technology to dive into this new system. Like me, however, they quickly recognized that COVE is user-friendly, even intuitive. They also appreciated the versatility of tools it provided us all, a versatility we had not found anywhere else.

After a school year of exploring and actively using COVE, I have discovered that it is not just another learning management system. COVE uses technology to facilitate key pedagogical goals of the Victorian literature classroom. COVE offers, especially through its timeline and map, ways to discuss the historical and cultural context of the long Victorian period. Through the annotation tool, students enter scholarly discussions. COVE Editions, such as that of Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market,” which I had both my upper- and lower-division students read, model scholarly discussions. Those editions, which are quickly becoming more numerous, also provide critical works that we can use to prepare students for their annotations and for their research with scholarly articles.

I am staying in the COVE. It is a digital pedagogy platform in which I—a still-not-technology-savvy professor—am free of technology worries. On the basis of the money students save in texts, COVE pays for itself, and, for me and my students, COVE’s pedagogical rewards are even more valuable.