Created by Sierra Windham on Thu, 11/14/2019 - 12:28

Description:

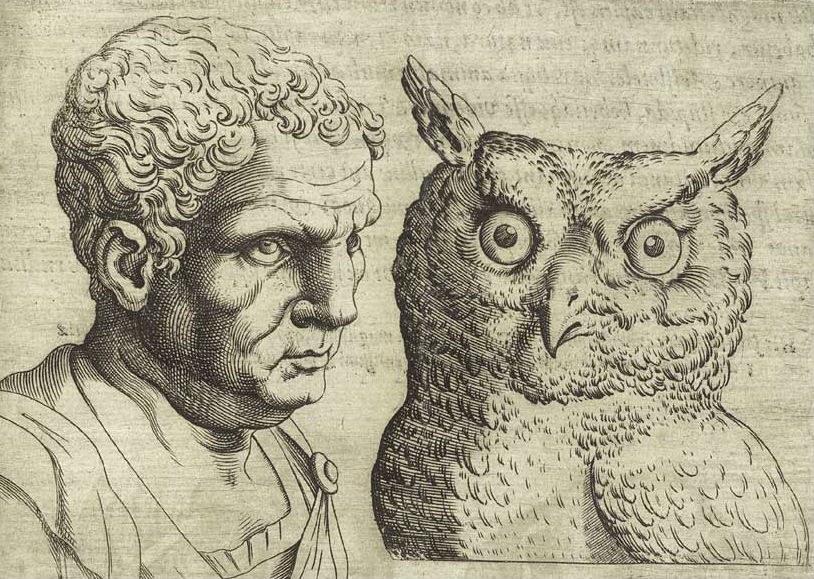

Physiognomy in Charlotte Brontë's time was likely similar to our own recent boom in the astrology field, though both are practices of divination tracing back to 500-200 B.C. The Greek philosopher Pythagoras was known to carefully select his students based on their physical attributes, which he believed was a surefire method of choosing the most gifted and skilled (just try to imagine this practice setting today's college entry standards!). As physiognomy evolved through the centuries, varying beliefs attached to this practice have entered the conversation; for example, one of the most popular forms of physiognomy was to compare human faces alongside those of animals. It was believed that if someone's facial features closely resembled, for example, a lion, that this person would in turn carry the lion's characteristics (bravery, leadership, etc). In this way, the common astrological practices of today aren't too different.

Of course, physiognomy also served a more malevolent purpose; with the spread of urbanization and subsequent rise in crime, anxiety mounted around the idea of whether or not a person’s motives could be distinguished by mere appearance. In answer to these questions, Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso asserted that certain facial features signaled trustworthiness and virtue, while certain other traits—interestingly, features he himself did not have—indicated “evilness” in the individual. These latter selected features typically targeted people who did not fit European beauty standards, which is why small noses and round eyes were considered to mark good character. Almost everything outside of this selected sphere (upturned eye shapes, large noses, protruding jaws and chins) were believed to indicate a criminal. Thus, physiognomy was often employed as an outright racist tool.

Johann Lavater, a Swiss writer, philosopher, and physiognomist, was particularly interested in the forehead as a point of focus; so too is Jane Eyre when, after being caught gazing at Rochester, examines the exposed skin beneath his hairline: "He lifted up the sable waves of hair which lay horizontally over his brow, and showed a solid enough mass of intellectual organs, but an abrupt deficiency where the suave sign of benevolence should have risen" (Brontë 120). We are later offered an instance of another character using physiognomy to distinguish characteristics, though this time through the lens of the elite upper class. Lady Ingram, upon spying Jane, says to Rochester: "'I am a judge of physiognomy, and in hers I see all the faults of her class'" (Brontë 160).

Beliefs from nineteenth-century physiognomy practices are still prevalent today in the common assumptions we hold towards people or fictional characters with certain physical features: for instance, crude and deceitful antagonist characters (Mr. Dursley in Harry Potter) are often depicted as ruddy, overweight, and with small, beady eyes. Such examples prove that these long-held appearance ideals are deeply ingrained into our cultural collective consciousness.

“Aspects of Lavaterian Physiognomy in Nineteenth-Century Literary Portraiture.” Physiognomy in the European Novel: Faces and Fortunes, by GRAEME TYTLER, Princeton University Press, 1982, pp. 208–259. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zvx9r.11.

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre, edited by Deborah Lutz, New York, NY, 2016.

“Picturing the Criminal: Photography and Criminality in the Nineteenth Century.” Capturing the Criminal Image: From Mug Shot to Surveillance Society, by Jonathan Finn, NED - New edition ed., University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis; London, 2009, pp. 1–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv09q.4.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Part of Group:

Artist:

- GIAMBATTISTA DELLA PORTA