Milan

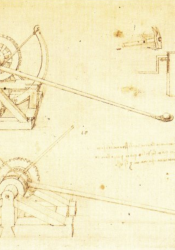

After settling in Milan and working as a Renaissance defense contractor under his patron, Il Moro, da Vinci drafted mechanical military designs that explored his idealized properties of complex technical processes, which included the his interpretation of the catapult.

Source:

Moon, F. C. (2016). Machines of Leonardo Da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux: Kinematics of Machines from the Renaissance to the 20th century. Place of publication not identified: SPRINGER.

Parent Map

Coordinates

Latitude: 45.464203500000

Longitude: 9.189982000000

Longitude: 9.189982000000