The breadth of essays exploring the COVE toolset already testifies to the platform’s flexibility to enhance pedagogy both in-person and remotely. These essays have discussed COVE’s applications to poetry, the construction of geospatial timelines, and mounting virtual art exhibitions, as well as the cost-effectiveness and user-friendliness of the toolset. My experience extends to teaching fiction in interdisciplinary courses populated by a range of undergraduate majors that have been delivered by necessity in a hybrid format. My students’ learning engagement with COVE has been overwhelmingly positive, and our shared experience suggests further evidence of the pedagogical value of creative digital tools in innovating humanities coursework. Other instructors have written about teaching poetry with the annotation tool; I’ve used it for canonical and noncanonical short fiction and intend to use it for longer form texts in future.

Through its annotation function, COVE provided a crucial framework for enabling my students to immerse themselves in the unusual opportunity to co-produce our materials of inquiry.

This kind of active participation was especially welcome in the time of Covid, when students and instructor alike were soon bored being stuck in little boxes on the screen. Annotation assignments took some of the impersonal distance out of distance learning; it inspired students to get intellectually invested in the materials, as well as in each other. As an interactive platform that can foster a true (if virtual) community of young scholars willing to share and build upon one another’s insights, COVE provided the space for all students to influence the trajectory of our analysis. Moreover, generating annotations helped students gain sufficient linguistic, cultural, and historical context to appreciate how and why the seemingly old-fashioned literary texts on our syllabus were indeed relevant enough to include in their Honors curriculum. On an interrelated level, honing their close reading skills with the aid of shared annotated stories enriched our discussions of our texts, led to more astute conclusions, and promised to pay further dividends for students when analyzing other genres and textualities.

Backstory:

When I decided to add COVE to my syllabus for the spring 2020 semester, I had no way of knowing that my pedagogical experiment was about to coincide with arguably the strangest, most unsettling academic year in history. But the timing could not have been better.

I teach in my university’s Honors College, and my courses are always multidisciplinary. My goal has been to balance traditional learning objectives (including critical thinking, close reading, sophisticated analysis, original thesis generation, thought-provoking interpretations) and innovative technologies. I needed options that didn’t require university resources, expensive subscriptions, or special technology that my institution didn’t already provide. I also teach on the South Carolina coast, in a hurricane zone and, even pre-Covid, flexibility in course delivery has always been critical. Before trying COVE, I was in the habit of designing assignments that allowed students to practice marketable real-world writing, content creation, and presentation skills, while providing me with fresh ways to engage with and assess student ideas in place of—or alongside—the traditional term paper. My university’s recent enrollment means I rarely teach an English major and, so, asking students to craft a conventional literary analysis for its own sake started to feel increasingly like an academic exercise—and one that didn’t keep pace with their technology-saturated experience of shared, interactive, and public reading and writing.

Teaching literature to non-English majors presents unique challenges. Assigning a piece of literature from my field—a Dickens, Brontë, or Collins novel, say—would likely trigger panic attacks. These books seem too stiff, too heavy, too distant. On the other hand, when I’ve tried to mix things up a bit and add in some “pop lit” fare—a neo-Victorian novel, for instance, or a noncanonical fin de siècle crime thriller—students sometimes have trouble figuring out what to do with it. These texts seem too flimsy, too cliché, too superficial. I often found myself struggling to keep students engaged on both fronts. I’ve long recognized that at least one of the major impediments was that students weren’t equipped with the necessary contextual knowledge to make sense of the material; they would generally skip over footnotes (if any were provided) or be in too much of a rush to stop and look up terms they didn’t understand. We hunted down terms together during class to facilitate discussion, but of course time was limited and we could never address every angle of the text that confused them. It was a cumbersome, inefficient way to move through stories that were supposed to be fast-paced and suspenseful entertainment. Plus, more often than not, I was the one doing the heavy lifting, pointing out passages I thought they needed clarified. I wanted students to be able to think about and engage with our texts in a more individualized, active, and immediate way.

The Courses:

I first used COVE in the spring semester of 2020 when I was teaching two sections of an interdisciplinary Honors topics course with the imposing title, Great Themes in the Humanities. Our special topic was more manageable: Millennial Sherlock Holmes: Adventures in Crime, Culture, & Media. I used COVE again the following semester, fall 2020, in a similar way and for a different version of the Great Themes course, Crime Fiction: The Entertainment Value of Violence & Villains. This time, my sections began with Arthur Conan Doyle, then moved on to other late Victorian and early twentieth-century crime fiction. COVE’s rebrand as the Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education perfectly suits my tendency to move between literary periods as well as the interdisciplinary nature of my courses. (It also saves me having to apologize for applying the toolset to texts well beyond even the long nineteenth century!)

My students are all members of the Honors College, but otherwise come from the full range of academic disciplines on campus. Given my institution’s demographics, Humanities has been the least represented College in each classroom. It’s an obvious bonus to teach Honors students who are academically motivated and curious. However, so far, not one of them has been an English major and only a few have been humanities majors. Most of them do not identify as readers and almost all of them are self-conscious about their (usually solid) writing abilities. More often than not, they will confess to not having written a “real paper” since high school, much less read a full book—much, much less any fiction. During the 2020 semesters, my courses were filled predominately with majors in the hard sciences. In short, students did not have much familiarity with our course topic, time periods, or reading selections.

Because I believe it is important for students to build expertise in a textual-based, collaborative, professional space, and because I love footnotes and all things peritextual, the COVE annotation tool was ideal for my diverse classrooms. What could be more appropriate for courses dedicated to crime fiction than reading like a detective: hunting down, investigating, and subjecting passages to forensic close readings? Peering at the clues provided by the text and putting them together to draw conclusions? Solving mysteries of theme, cultural contexts, meaning?

I had great expectations. I expected annotations to force nonreaders to read. I expected annotations to encourage students to slow down and pay attention to what they read. I expected annotations to introduce students to language, cultural attitudes, generic conventions, and social history that they were unfamiliar with in a hands-on, meaningful way. I expected annotations to exert some peer pressure in terms of the quality of student effort and the polish they’d put on their contributions. These expectations were mostly realized. Eventually.

The First COVE/Covid Semester:

The pandemic impacted my spring and fall 2020 courses in different ways, so I’ve had the opportunity to use essentially the same COVE annotation assignments in both the classroom and distance learning environments. I initially envisioned using the annotation tool under typical in-person circumstances, but it was an added benefit that I could seamlessly move this piece of the course totally online in March 2020. Students appreciated the stability: that part of the class was one thing that did not change when basically everything else about the semester had. My fall 2020 sections were slated to be hybrid, which meant there was a good deal of uncertainty surrounding how much classroom time we’d actually have. Using COVE was again a reliable constant under changeable conditions.

Our first hurdle was rather immediate and entirely out of our control: my institution’s firewall that basically prevented students from creating their own NAVSA/COVE accounts. I mention this because it was obviously frustrating and inconvenient for all involved and yet the COVE team was unfailingly helpful and encouraging until we got the problem fixed. COVE administrators responded to me quickly, assisted students individually if necessary, and then changed their email service to accommodate robust firewalls like ours.

The benefits of COVE tools far outweigh any tech glitches or apprehension an instructor might feel about implementing a new platform into a course. I held off adopting these tools for several semesters out of similar apprehensions and feeling too busy to try something new. But having the capability to customize your own free anthologies is exciting, especially when you’re studying obscure texts and/or teaching an interdisciplinary course. For the first time, I had one central and convenient location for all of our materials and access to the tools cost students a total of $10. I wasn’t bombarding students with links to rare texts from all over the internet. I had no trouble at all pasting digitized versions from the public domain into my anthologies. And once I shared COVE’s indispensable tutorials with students, I rarely got student messages wondering what they were supposed to do, where, or how. That they were able to navigate COVE’s annotation toolset with facility is made clear in a sample comment from a student:

First, I want to mention the positive view I have of the set-up of the digital annotations. I found that the website made formatting and understanding my annotations very simple in comparison to other websites I’ve used in the past. This was a positive and allowed me to reference back to the material with ease.

The spring 2020 semester—my first semester with COVE and with Covid—began as planned, with students’ annotations complementing our class discussions. We practiced annotating together in class with the first several chapters of Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet (1887) projected onto a screen, and then they tried it themselves once their COVE accounts were sorted out. Their preliminary efforts not only gave us discussion material, but also often steered our focus in directions I hadn’t planned and yielded insights I hadn’t scripted. We were all getting comfortable using the annotation tool—and then the semester was turned upside down and we suddenly moved online.

There was a significant distinction between the quality of student engagement prior to instituting annotation exercises and afterwards. Before students had completed their first annotation assignment, we began working with one of Conan Doyle’s earliest and most famous Sherlock Holmes adventures, “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891). Students were reticent during classroom discussion. We had difficulty with anything approaching close reading. That is, it was difficult to get students to talk about anything beyond plot and character; there seemed little interest in or ability to connect dots to generate deeper thematic meanings for the piece. Somehow, their first real experience with Sherlock Holmes wasn’t quite what they had imagined. They weren’t impressed with the disguises, they didn’t appreciate the gravity of the incriminating photograph, and they were too distracted by the Victorian vocabulary to follow the actual case. I’ve taught these tales enough over the years to know that these reactions are common. It takes a good part of the semester for students to catch on with the style and time period, and I’m doing all of the legwork when it comes to scaffolding each discussion.

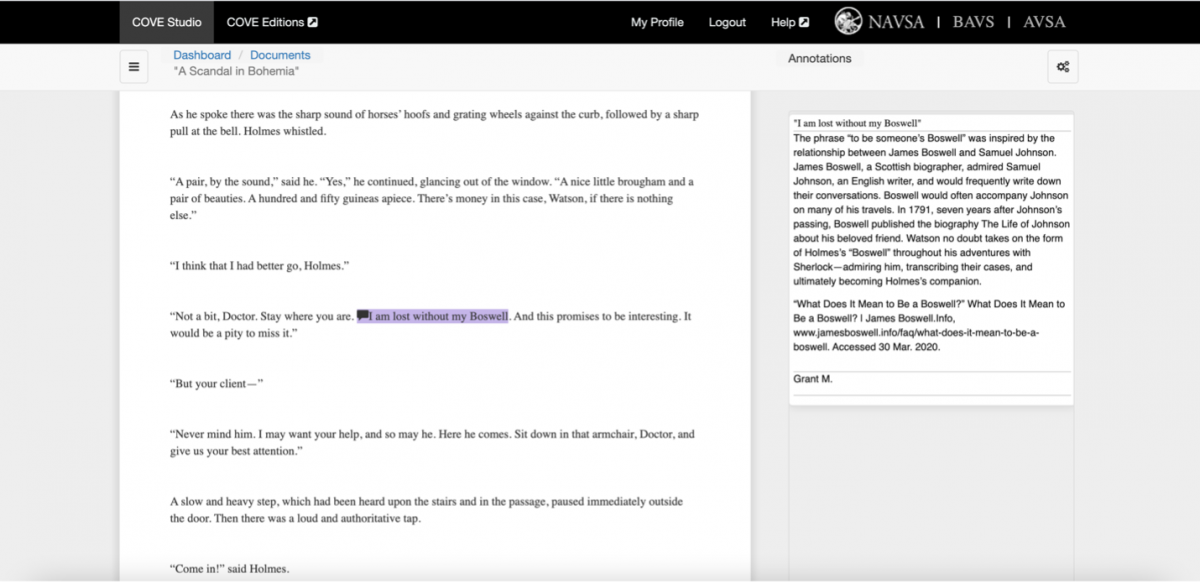

Once students received their first individual annotation assignments, however, discussions (by this point via Zoom) took a decided upturn. For example, as seen below, one student picked out Holmes’s previously enigmatic allusion to Boswell, a passage from the story that had initially been totally ignored by the entire class during discussion. Another student provided valuable cultural context by explaining the suggestiveness of Irene Adler’s status as an opera singer, and another gave a historical overview of the cabinet photograph. The linguistic, cultural, and historical information students tracked down for their annotations began to crop up organically in their virtual discussion, sidebar chat, and supplemental journal entries.

A student makes sense of a puzzling textual allusion to James Boswell in Arthur Conan Doyle’s “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891).

A student makes sense of a puzzling textual allusion to James Boswell in Arthur Conan Doyle’s “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891).

These contributions deepened our class discussions considerably and got students much more fully engaged in listening to and learning from one another as sources of information; they no longer looked to me as the sole purveyor of knowledge, but were key participants in the information flow. Their intellectual wheels were churning, and our class discussions began to get well past basic plot and character and to delve deeper to truly model the critical value of close reading.

It took me until my second semester with COVE, fall 2020, to establish some best practices, but I can say the annotations tool works effectively regardless of teaching modality. I prefer to work with students and texts in person because it feels more efficient and energizing, but the overall pedagogical payoffs for my students were the same.

Noncanonical Crime, Context, & Curiosity…The Second Time Around:

So, the first semester on Sherlock dealt with more canonical texts; the second dealt with largely noncanonical works. From my perspective, working with noncanonical texts was more fun, but because of their limited exposure to even our famous authors, I don’t think students distinguished any difference in terms of annotating these.

This time, I knew better what to expect in terms of their reactions to the assignment and where they were likely to stumble. Early on, my task was clearly to convince students that reading with an eye to annotate didn’t have to “ruin” their enjoyment of the material. Instead, annotating was meant to enrich their reading experience, knock the dust off their close reading skills, and reward critical thinking. After all, how could they figure out themes or cultural statements or the value of literature if they had no idea what they were reading?

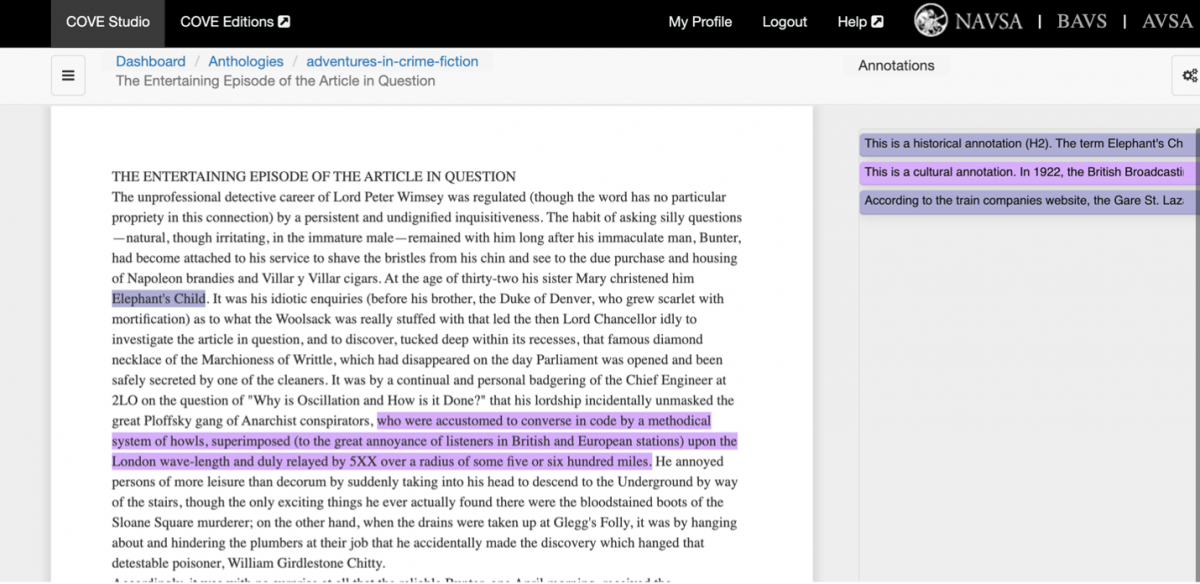

Student annotation of opening paragraph of Dorothy Sayers, “The Entertaining Episode of the Article in Question” (1928)

Student annotation of opening paragraph of Dorothy Sayers, “The Entertaining Episode of the Article in Question” (1928)

Closely reading a dense opening like the one above together as a class in fall 2020 illustrated how textured even our one-time mainstream, pop fiction narratives really were (and therefore how interesting to annotate). In the beginning, it was a tough sell.

Here’s how I did it.

I assigned four stories for each batch of annotations. Each student was responsible for one annotation per story. My first requirement was this: no double-dipping. If a classmate annotated a term or passage, then it was off-limits. This worked fine and gave students some incentive not to procrastinate or slack off. There were always certain students who worried all the “good parts” would get taken right away, which I of course assured them was impossible.

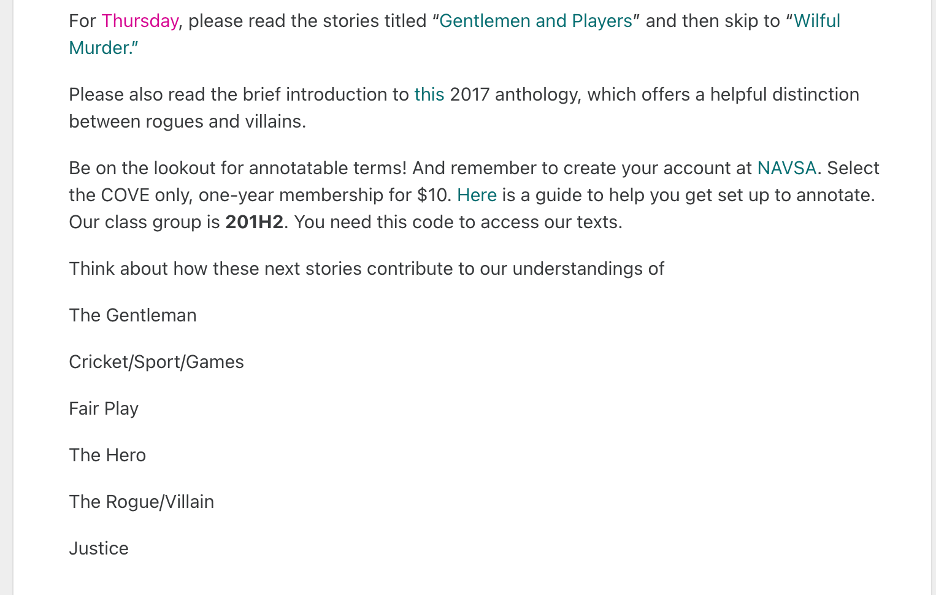

Batches of annotations were due every few weeks, and students would have participated in class discussions of the stories they were annotating during that period. This allowed them to ask questions during class, double-checking if their interpretation of a passage was viable or whether a particular section was, as they put it, “annotatable.” I found it helpful to remind them of specific themes or concepts we were on the lookout for when choosing their phrases.

Reminding students of key concepts in class discussion will yield thematic coherence.

Reminding students of key concepts in class discussion will yield thematic coherence.

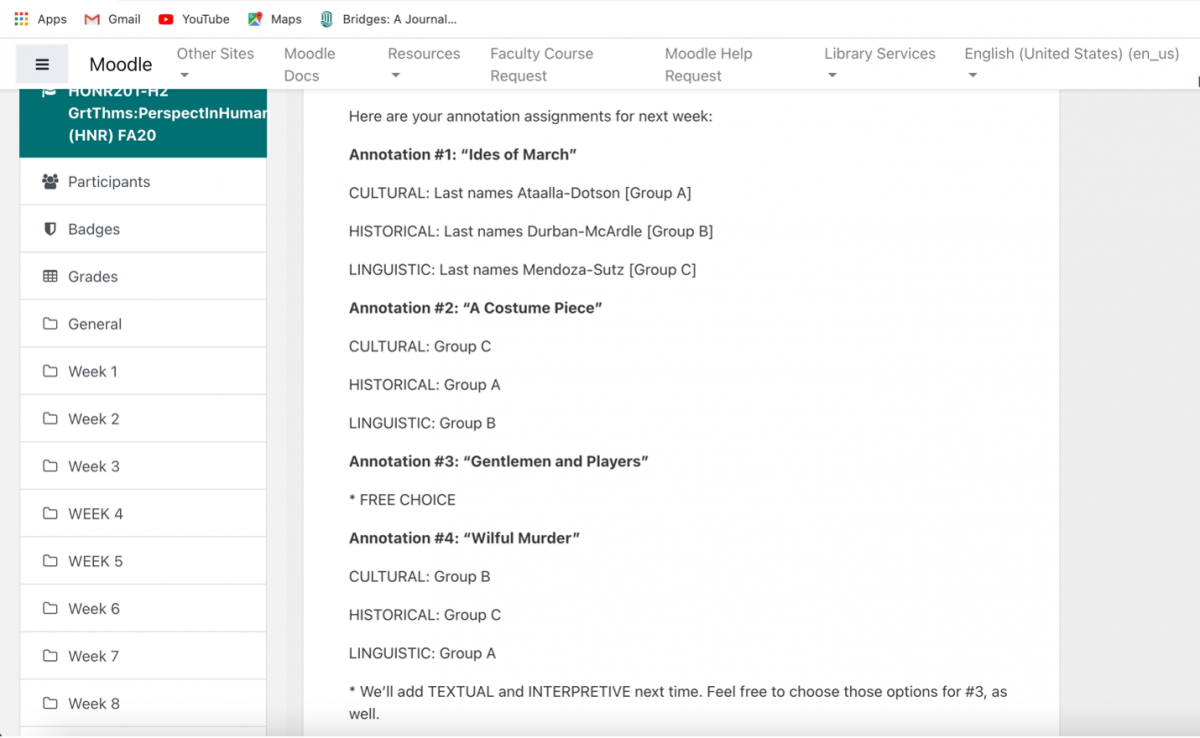

I divided students alphabetically into groups. Each group then rotated through the various annotation categories for each story. This ensured that students were able to practice every type of annotation and find different kinds of passages that struck them.

Example of annotation category breakdowns by story in fall 2020

Example of annotation category breakdowns by story in fall 2020

Linguistic, Cultural, and Historical remained the most commonly chosen categories across sections when students had free choice, and they claimed in final reflections to prefer Linguistic overall. This was interesting because I generally found their work in every other category to be more creative and sophisticated than their Linguistic choices.

First of all, along with Laura Rotunno in her COVE teaching article, “Trial and Success,” I was in mild shock at the terms students chose to annotate. How could they feel the need to define “revolver” and “cupboard” when terms such as “blackguard” and “billycock” appeared in the same tale?

A second heads-up about Linguistic: if you intend for students to do more than simply paste a dictionary denotation (or, worse, the first dictionary denotation they find regardless of context), then you should let them know. Here’s an example of what to expect if you don’t spell out that you are looking for more than a pasted definition (which I was): “The revolver was patented by Colt Paterson in Britain in 1835, and in America in 1836. The first production model was made March 5th, 1836.” Along with Dr. Rotunno, I figured out right away that an introduction to (or reminder of) the OED would be imperative for higher quality contributions in the Linguistic category. We also took this opportunity to practice explication skills.

A better Linguistic effort—once we discussed the necessity of indicating the term’s significance to its context—is the following gloss on the word “ignominious,” taken from E.W. Hornung’s mostly forgotten Raffles tale, “A Costume Piece” (1898):

This stuck out to me because I have never come across this word before. I looked it up and the definition was ‘humiliating, degrading’ (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ignominious). Raffles is hiding in the wardrobe and is found. He thinks it’s humiliating that he’s now been found and captured. This isn’t usually like him.

You can see that this student feels comfortable personalizing her annotation (something that is traditionally discouraged in formal academic writing) and connects the term to the context of the narrative, even though she mistakes which character is captured. She’s right, at least; it isn’t like Raffles to get caught hiding in a wardrobe—and he doesn’t. (His sidekick, the narrator, does.) Still, it was progress. And several students noted the particular value of the Linguistic category of annotations in getting them to read more closely and with deeper understanding. Jett provided a representative response:

I personally loved the linguistic annotation category, mostly because there was a LOT of language that I just didn’t understand in the stories. This category helped me paint a clearer picture of how the characters would communicate with each other, and it helped me figure out some of the character relationships more clearly.

Students looked for clearer delineations between Cultural and Historical and fretted over whether they were getting these categories “wrong.” We landed on tagging an item Cultural when it had to do with prevailing attitudes, behaviors, or practices. We tagged an item Historical when it concerned an actual person, place, thing, date, or event. Despite repeated discussion (individually and class), posted models, real-time walkthroughs, and the fact that no one ever lost a single point for mixing them up or combining them, this anxiety persisted throughout the semester. Despite this consternation, some students reported finding these the most valuable in helping to generate fuller meaning for the stories. Tyler, for instance, reflected that his “favorite categories were the historical and cultural annotations” since “these categories helped put the stories into a broader perspective by talking about customs and ideas from the times the stories were written.” His classmate Will offered the assessment that “even though most of them required more research than others to understand, the cultural aspects of these stories really helped capture the time period and elaborated on what the author was incorporating into the story.” For her part, Rebecca added that “because we are unfamiliar with some of the slang and concepts from the 19th and 20th centuries, [cultural] annotations gave me a reason to look up the meaning of some of the people, architecture, events, and art that were well known during this time.”

Interpretive and Textual tags required significant explanation. Model student examples were most effective in demonstrating applications of those categories, and I walked students through several sample annotations during class discussion. We primarily used Textual to point out callbacks and allusions, e.g., to characters we had previously encountered, such as Sherlock or Watson, or to works by other authors, such as Shakespeare or Kipling (as in the allusion to The Elephant’s Child in the Sayers screenshot above). I encouraged them to relate material to other course texts and/or their own repertoire. Interpretive was trickier, and students tended to avoid that category. By the end of the semester, a few students bravely attempted it, usually in order to share something they liked or “got.” One student had this to say about G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown story, “The Secret of Flambeau” (1927):

Right away, this is an amazing way to continue the story. It literally, right at the opening ellipses, picks up from the end of the previous story. …I must again highlight just how good the author is with his writing. It is something so small, but has such an impact. Having the story start right off after the other in the heat of the moment works better than something like ‘Last time in Father Brown, blah blah...’

What I appreciate most about a note like this is that, again, it’s evident from the student’s style that he feels comfortable contributing something personal and authentic. It reminds me of a comment he would make if he raised his hand in the classroom. I find glimpsing personalities this way to be really helpful in gauging how students are engaging with the material and getting to know them better when our only interaction is via Zoom. And digital annotation assignments also encouraged stronger peer-to-peer engagement and camaraderie, as reflected in Rebecca’s comments: “I enjoyed completing these assignments and using the COVE website because it challenged me intellectually. I also like the idea that the annotations were open to all of our classmates so that we could see what fascinating annotations they picked out, too.”

The annotations definitely flipped the classroom, providing a real opportunity for students to learn from one another. It was interesting to discover what passages they’d gravitate toward, and, although I marked all sorts of passages I expected them to flock to, I was consistently surprised (and often pleased) by what they came up with when left to their own devices. As Carson suggested, the annotations “contributed to class discussions because I and many other classmates had a better understanding of these stories” and had the confidence to serve as “resident experts” on the information they’d uncovered through their peritextual analysis. Chances are, if one student found a phrase or a historical reference puzzling and worth annotating, then all benefitted from the elucidation of that textual moment. Digitally annotating helped students feel as though they were all collaborating on producing a deeper meaning for the text at hand, with each individual annotation adding to the team effort. This digitalized collaboration was especially valuable while in-person interactions were so limited under Covid conditions and we’d all become a bit Zoomed-out.

The following student note on Dorothy Sayers’s witty Lord Peter Wimsey mystery, “The Entertaining Episode of the Article in Question” (1928), plainly illustrates how the research required for annotations enriches the reading and analysis experience. Our syllabus included several crime narratives by Hornung, Chesterton, and Sayers that were meant to be “entertaining”—to their contemporary readers. A vintage author’s cleverness is easily lost in translation when students read as they ordinarily would (i.e., without having to annotate). The ways in which annotation helped let students in on jokes from bygone eras is made clear in my student Carson’s sharp reflections:

After research, you could see that the author was using a phrase that readers of that time would get or find funny. As current readers, we might have just glanced over that detail, but the annotations cause us to read in-depth and consider what the author is trying to say. I feel the annotations caused me to be a better reader and analyze the text.

Annotations solved some of the mystery of “what’s so funny” for twenty-first-century undergraduates, as you can see in the following student contribution on the French phrase sans-culottes below:

Sans-culottes is Jacques Lerouge’s alias. When Lord Peter exposes Lerouge as the thief who is impersonating a woman, he introduces him by saying he is known as Sans-culottes. This is significant because it describes Lerouge’s disguise. The French term sans-culotte means “without knee breeches” (https://www.britannica.com/topic/ sansculotte). Knee-breeches are defined as “trousers worn by men in the past” (https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/knee-breeches). When Lord Peter says Jacques Lerouge is known as Sans-culottes it means he does not wear pants and therefore is not dressed as a man. He is disguised as a lady’s maid in an attempt to steal diamonds.

We can see Sayers’s sense of humor with her nicknaming this criminal Sans-culottes. Sayers is having fun with her antagonist in this story and in this timeframe, readers would see this as a joke and find it funny. It also reinforces that the story is half comic since the “cleverest thief in the world” has a ridiculous and obvious nickname that gives away his disguise. We can see the gameplay between this most clever thief and Lord Peter trying to catch him. At the end of the story, Lerouge acknowledges how he was outplayed by Lord Peter.

Sans-culottes also connotes anti-aristocrat French Revolutionaries, which another student might choose as a Cultural or Historical annotation with the help of the OED.

Whether implemented in person or remotely, COVE’s annotations capability provided an incisive analytical tool that opened up in-depth critical insights—no matter the text under scrutiny—substantially deepening students’ perceptions of popular literature by enabling them to create links with cultural contexts. The crime narratives we read were intended for a popular audience and traditionally have not counted as Literature. I like the fact that this sent the message that any text has more to offer than students might initially expect, that even “popular” fiction yields plenty to dissect, interpret, and analyze. There is no chance a class could run out of annotatable pieces in any given story. I hope that the takeaway of every annotation assignment was that there’s always something—generic or historical or cultural or linguistic—to learn. As long as they are curious, then students are guaranteed to put every story down knowing something they didn’t know before.

Enabling students to annotate and share what interested them most in our readings expanded the value of these texts by illustrating the foundational significance of close reading. Asking them to explore the nuances of these texts showed students that any text—regardless of its status as canonical or commercial, famous or forgotten—is open to close, critical reading. The pop fiction assigned in fall 2020 was chock full of engaging and enlightening cultural and historical import, aside from any aesthetic considerations. The sustained exercise in annotation will, I hope, inspire students to apply this level of critical acumen and attentiveness to other types of texts, in their major disciplines and outside the classroom altogether.

Moreover, using the COVE annotation tool allowed me to get to know students’ individual personalities during semesters when I interacted with them most often as black boxes on Zoom. Back in the classroom, the COVE component of my courses will function much the same. Annotations are not formal papers, and so I find students’ writing voices to be much more genuine and relaxed. They are more likely to use first person, take some risks in sharing their reactions, and admit to not being certain about a detail in the narrative. I can’t overstate how valuable I consider this to be. Not only could I recognize a student’s sense of humor or family background based on their notes, but also several students reached out consistently throughout those two semesters to discuss their thoughts and reactions to readings. They definitely considered COVE to be a friendly, accessible platform for expressing their ideas about course readings without the burden of an overly academic style.

Control and the Flipped Classroom:

Without a doubt, integrating COVE annotations into my syllabus helped me become more responsive in my teaching practice. Having worked with our course material for a long time, I realized through this collaboration that I needed to adjust my perspective about the parameters of student knowledge (whether of a genre or historical period) and experience (with close reading practice or the OED). I also realized that valuable student insights were likely to emerge if I relinquished some control over the learning experience. That said, the earlier example of Raffles hiding in the wardrobe raises a particular challenge inherent in the flipped classroom: sometimes students will still get it totally wrong and their mistakes are out there in writing for the rest of the class to see. My favorite example of this comes from a serious student who produced careful work all semester long. He composed the following annotation after all of my failproof and painstakingly developed strategies were deployed: multiple real-time, interactive walkthroughs of what to do and how, as well as an introduction to the OED with hands-on practice annotations and solid student models. He annotated another one of E.W. Hornung’s Raffles tales, “Gentlemen and Players” (1898). Much of the Raffles tales turn on veiled reference as well as clever wordplay and innuendo. The stories contain a number of contemporaneous in-jokes.

The story is bursting with late Victorian cultural allusions, clear right from the cricket reference in the title (in fact, we used the title to practice researching language we falsely assume we don’t need to research).

So, the narrative centers on cricket matches and an invitation to a cricket week in the country.

Here’s the annotation:

After looking up ‘Harrow Eleven,’ I found that it refers to a code of football that is played between two teams with eleven people on the team. I also looked up the definition of ‘harrow’ and found that the dictionary definition is ‘cause distress to.’ That means that referring to Young Crowley as ‘Last year’s Harrow Eleven’ probably means that he was one of the worst on the team.

I don’t know why the student substituted football for cricket, but it’s not a bad stab at the rest of it, given the definition of “harrow” with which the student is operating. In addition to emphasizing the value of the OED, entries such as this one convinced me that I was taking too much cultural and contextual knowledge for granted. With a more realistic sense of what students were bringing to their interpretations, I was better able to point them in the right direction for locating information to strengthen their comprehension of a narrative. In fact, we revised the Harrow Eleven annotation as a group, which generated laughs and culminated in a collective epiphany. I also realized I should incorporate a revise option into my next iteration of the assignment and perhaps try to have students peer review each other’s contributions before posting.

Reflections & Connections:

In the space of each of these semesters, both conducted most often via Zoom, many students indicated they had basic experience with annotating in high school. They learned that we were operating on another level after the first set of annotation grades came out. Since many of them did not identify as readers and/or their major disciplines did not involve the kinds of notes our assignment called for, these students did not fully understand what they were expected to do. (And since I didn’t anticipate the extent of the support they needed until their first submissions came in, I included “extra” annotation opportunities toward the end of the semester, which a majority of students chose to complete.)

According to their end-of-semester reflections, students most appreciated the value of focusing intently on a single annotation, rather than a scattershot approach; the uniqueness of these assignments in cultivating close reading skills; and the applicability of techniques learned in this class to other courses. Hannah reflected, “I loved that we were able to focus a lot on one specific annotation per story because it allowed me to actually spend time on it and learn about it rather than just highlighting every other sentence.” Concentrating on one particular annotation further enhanced the value of these assignments in building up students’ close reading skills. The COVE annotation toolset helped my students pay deeper attention to their reading and to level-up their critical thinking skills. According to Tyler,

The biggest thing that I learned from these assignments is to read stories and texts more closely as there are quotes that add a deeper meaning to the overall story. [Searching for terms] led to me rereading almost every story to try and find what to annotate, but that allowed me to catch things I missed during the first time reading.

And Konnor found a new study strategy:

I do not usually do annotations in my other classes or really take notes while reading, but I may have to start because of how much easier it made the text to understand. The annotations overall have made me believe that if you take notes the right way and interact with the text it actually does make a difference for the better.

There was a learning curve for all of us, but once I saw how much support they needed and where, and once they got the hang of what was expected, students were better prepared to appreciate the material and the exercise. Critical reading skills benefit all disciplines and courses of study, which makes this COVE tool suit an interdisciplinary course particularly well. What’s more, having a range of annotation categories from which to choose gives students of diverse academic backgrounds and intellectual pursuits the freedom to apply their individual interests to each assignment; in Rebecca’s terms, “instead of just writing a summary of the material, the annotations allowed for us to be creative, as well as improving our cultural awareness.”

My COVE-enhanced pedagogical experiment convinces me that annotations can also translate productively across domains. I envision expanding the insights and practices of these course experiences in a future iteration, where students might annotate all manner of diverse textualities and cultural media: “agony columns” in periodicals, museum artifacts, archival forensic reports, daguerreotypes, you name it. I’m eager to connect students with other COVE tools, including a collaborative critical edition of a full-length novel, complete with accompanying images, written by an underrepresented author or even an annotated neo-Victorian novel. I expect the pedagogical afterlives of these initial COVE-enhanced courses to keep going strong, transcending my literature-based courses so that my rhetoric and media students are annotating political speeches and cultural critiques as soon as they’re published. Invigorated by our collaboration with the digital toolset, many of my non-humanities majors have discovered that the humanities generally—and literature specifically—are interesting, adaptive, and most certainly worth exploring.