Appendix B: Contemporary Reviews

These reviews are initial reactions to the 1891 edition of Wilde’s collection of short stories, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crimes and Other Stories. The first five are British reviews from August and September of 1891, while the last is an American review published in February 1892.

Unsigned notice, The Graphic, vol. 94, 22 August 1891, p. 221.

[The Graphic was a weekly illustrated newspaper published from 1869 to 1932. Founded by artist William Luson Thomas, it was very influential in the art world.]

The humour of Oscar Wilde’s jeu d’esprit [1] thus entitled is of a very different order. As pure farce--and what can be better than farce at its best?--it deserves to live; for it is independent of passing circumstances, and is written with all the grave, simple, matter of fact seriousness which is more essential to farce than to tragedy. Nobody with the slightest sense of humour, or, for that matter, nobody with the strongest, can fail to enjoy the story of a man to whom murder presented itself in the light of a simple duty. It is worth all Mr. Wilde’s serious work put together. The stories which follow are also excellent, and their author is to be congratulated on having introduced an entirely new and original ghost to the world--no slight feat in these days. But for its degeneration into sentiment, the story in which it appears would be almost as good in its way as that of ‘Lord Arthur’s Crime.’

William Sharp, “Review,” The Academy, vol. 40, 5 Sept., 1891, p. 194.

[The Academy was a review of literature and general topics published from 1869 to 1902.]

Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime , and its three companion stories, will not add to their author’s reputation. Mr. Oscar Wilde’s previous book, though in style florid to excess, and in sentiment shallow, had at least a certain cleverness; this quality, however, is singularly absent in at least the first three of these tales. Much the best of the series is the fourth, the short sketch entitled ‘A Model Millionaire’, though even this brief tale is spoilt by such commonplace would-be witticisms as ‘the poor should be practical and prosaic’, ‘it is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating.’ There is much more of this commonplace padding in the story that gives its name to the book, e.g. ‘actors can choose whether they will appear in tragedy or comedy,’ &c., ‘but in real life it is different. Most men and women are forced to perform parts for which they have no qualifications,’ and so on, and so on, even to the painfully hackneyed ‘the world is a stage, but the play is badly cast.’ This story is an attempt to follow in the footsteps of the author of New Arabian Nights. Unfortunately for Mr. Wilde’s ambition, Mr. Stevenson [2] is a literary artist of rare originality. Such a story as this is nothing if not wrought with scrupulous delicacy of touch. It is, unfortunately, dull as well as derivative. ‘The Sphinx without a Secret’ is better. ‘The Canterville Ghost’ is, as a story, better still, though much the same kind of thing has already been far better done by Mr. Andrew Lang; but it is disfigured by some stupid vulgarisms. ‘We have really everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course, language.’ ‘And manners,’ an American may be prompted to add. A single example may suffice:

The subjects discussed were merely such as form the ordinary conversation of cultured Americans of the better class, such as the immense superiority of Miss Fanny Davenport over Sara Bernhardt as an actress; the difficulty of obtaining green corn, buckwheat cakes, and hominy, even in the best English houses … and the sweetness of the New York accent as compared to the London drawl.

It is the perpetration of banalities of this kind which disgusts Englishmen as well as ‘cultured Americans’. One should not judge the society of a nation by that of a parish; the company of the elect by the sinners of one’s own acquaintance. Mr. Wilde’s verbal missiles will serve merely to assure those whom he ridicules that another not very redoubtable warrior has bestirred himself in the camps of Philistia.

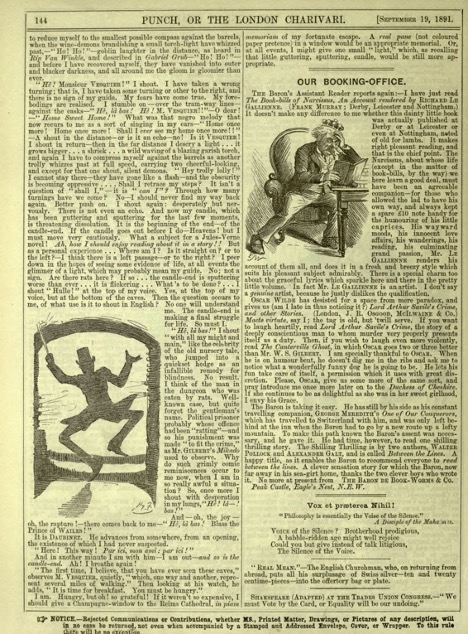

Unsigned, from “Our Booking-Office,” Punch, or the London Charivari, vol. 101, 19 Sept., 1891, p.144.

[Punch, a weekly magazine of humor and satire, was founded in 1841 by writer Henry Mayhew and wood-engraver Ebenezer Landells. It became a staple of British drawing-rooms; even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were counted among its readers. The review is written from the facetious guise of “the Baron’s Assistant Reader,” but is likely to have been written by the magazine’s editor at the time, Sir Francis Cowley Burnand (F.C. Burnand), an English comic and playwright.]

Oscar Wilde has desisted for a space from mere paradox, and gives us (am I late in thus noticing it?) Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, and other Stories, (London, J.R. Osgood, McIlwaine & Co.) Macte virtute, [3] say I; the tag is old, but ‘twill serve. If you want to laugh heartily, read Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, the story of a deeply conscientious man to whom murder very properly presents itself as a duty. Then, if you wish to laugh even more violently, read The CantervilleGhost, in which Oscar goes two or three better than Mr. W.S. Gilbert. [4] I am specially thankful to Oscar. When he is on humour bent, he doesn’t dig me in the ribs and ask me to notice what a wonderfully funny dog he is going to be. He lets his fun take care of itself, a permission which it uses with great discretion. Please, Oscar, give us some more of the same sort, and pray, introduce me once more later on to the Duchess of Cheshire. [5] If she continues to be as delightful as she was in her sweet girlhood, I envy his Grace.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17216/17216-h/images/v01intro01.png

W.B. Yeats, “Oscar Wilde’s Last Book,” United Ireland, 26 Sept., 1891, p. 5.

[William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) would become a highly successful poet and one of the foremost figures of twentieth-century literature. His assessments of literary works, including Oscar Wilde’s, would influence critics for generations.]

We have the irresponsible Irishman in life, and would gladly get rid of him. We have him now in literature and in the things of the mind, and are compelled perforce to see that there is a good deal to be said for him. The men I described to you the other day under the heading, ‘A Reckless Century,’ thought they might drink, dice, and shoot each other to their hearts’ content, if they did but do it gaily and gallantly, and here now is Mr. Oscar Wilde, who does not care what strange opinions he defends or what time-honoured virtue he makes laughter of, provided he does it cleverly. Many were injured by the escapades of the rakes and duellists, but no man is likely to be the worse for Mr. Wilde’s shower of paradox. We are not likely to poison any one because he writes with appreciation of Wainewright---art critic and poisoner---nor have I heard that there has been any increased mortality among deans because the good young hero of his last book tries to blow up one with an infernal machine; but upon the other hand we are likely enough to gain something of brightness and refinement from the deft and witty pages in which he sets forth these matters.

‘Beer, bible, and the seven deadly virtues have made England what she is,’ [6] wrote Mr. Wilde once; and a part of the Nemesis that has fallen upon her is a complete inability to understand anything he says. We should not find him so unintelligible--for much about him is Irish of the Irish. I see in his life and works an extravagant Celtic crusade against Anglo-Saxon stupidity. ‘I labour under a perpetual fear of not being misunderstood,’ he wrote, a short time since, and from behind this barrier of misunderstanding he peppers John Bull [7] with his peashooter of wit, content to know there are some few who laugh with him. There is scarcely an eminent man in London who has not one of those little peas sticking somewhere about him. ‘Providence and Mr. Walter Besant [8]have exhausted the obvious,’ he wrote once, to the deep indignation of Mr. Walter Besant; and of a certain notorious and clever, but coldblooded Socialist, [9] he said, ‘he has no enemies, but is intensely disliked by all his friends.’ Gradually people have begun to notice what a very great number of those little peas are lying about, and from this reckoning has sprung up a great respect for so deft a shooter, for John Bull, though he does not understand wit, respects everything that he can count up and number and prove to have bulk. He now sees beyond question that the witty sayings of this man whom he has so long despised are as plenty as the wood blocks in the pavement of Cheapside. As a last resource he has raised the cry that his tormentor is most insincere, and Mr. Wilde replies in various ways that it is quite an error to suppose that a thing is true because John Bull sincerely believes it. Upon the other hand, if he did not believe it, it might have some chance of being true. This controversy is carried on upon the part of John by the newspapers; therefore, those who only read them have as low an opinion of Mr. Wilde as those who read books have a high one. Dorian Gray with all its faults of method, is a wonderful book. The Happy Prince is a volume of as pretty fairy tales as our generation has seen; and Intentions hides within its immense paradox some of the most subtle literary criticism we are likely to see for many a long day. To this list has now been added Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories (James R. Osgood, M’Ilvaine, and Co.). It disappoints me a little, I must confess. The story it takes its name form is amusing enough in all conscience. ‘The Sphinx without a Secret’ has a quaint if rather meagre charm; but ‘The Canterville Ghost’ with its supernatural horse-play, and ‘The Model Millionaire’, with its conventional motive, are quite unworthy of more than a passing interest….

Surely we have in this story something of the same spirit that filled Ireland once with gallant, irresponsible ill-doing, but now it is in its right place making merry among the things of the mind, and laughing gaily at our most firm fixed convictions. In one other Londoner, the socialist, Mr. Bernard Shaw, I recognize the same spirit. His account of how the old Adam gradually changed into the great political economist Adam Smith is like Oscar Wilde in every way. These two men, together with Mr. Whistler, the painter--half an Irishman also, I believe--keep literary London continually agog to know what they will say next.

Unsigned review, The Nation, 11 Feb., 1892, vol. 54, no. 1389, p. 114.

[The Nation is the oldest continuously published weekly magazine in the United States. Founded in 1865 as a successor to the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, it has since undergone many iterations; between 1881 and 1918, it served as the literary supplement for the New York Evening Post. Its Literary Editor at the time of this review was Wendell Phillips Garrison, son of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.]

Mr. Oscar Wilde’s little volume might be called a collection of skits; and this attitude of the gentleman towards matters in general is a familiar one. Yet a subjectivity of method on his part, which all who were happy enough to see him in this country a few years ago [10] will somewhat painfully remember, nearly disappears in his stories, leaving his method freer and himself a more agreeable satirist than might have been supposed. We detect little of the rebuking knee-breeches or the exemplifying forelock here, while there is an abundance of wit and invention. “The Canterville Ghost” and “The Sphinx Without a Secret” are easily better than the two remaining sketches; in the former, the irreverent treatment by an American family of an English ancestral ghost is the happy subject of a happy treatment. The story which gives the book its name is a stiffish dose of trying to be funny, but its opening chapter is worth reading for as clever a picture of a social function as we have lately seen. The volume is charmingly bound and printed, only the title-page of each story betraying any eccentricity, and so we may feel that we have got off as easily as could be expected.