Dr. Graham Price

Dr. Sandra Leonard

Were we at the mercy of such impressions as Art or Life chose to give us? It seemed to me to be so.

Oscar Wilde “The Portrait of Mr W.H.”

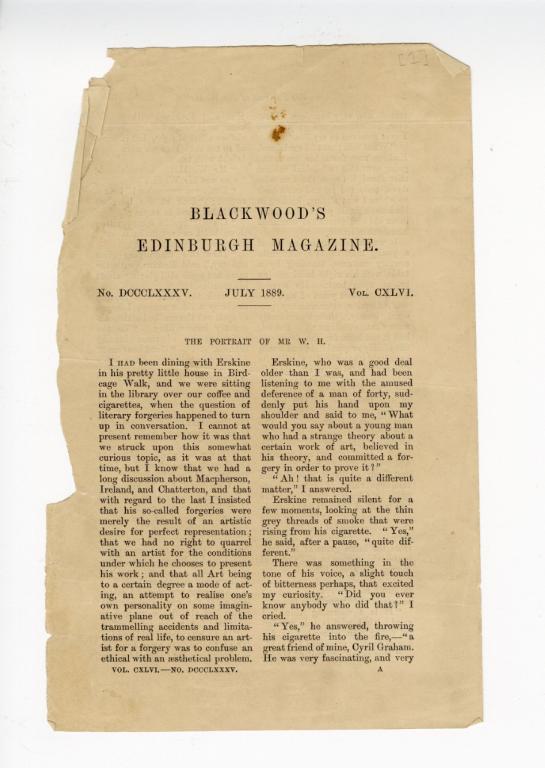

“The Portrait of Mr W.H.” was first published in Blackwood's Magazine in 1889. Though an enlarged edition was planned and publicly announced as The Incomparable and Ingenious History of Mr W.H., it was not released during Wilde’s lifetime. The expanded text promised to be almost twice as long as the Blackwood’s version with a frontispiece by Charles Ricketts, but, following Wilde’s bankruptcy sale in 1895, it was thought to be lost forever. However, a manuscript revision now held by the Rosenbach Museum and Library came to light after Wilde's death and was published by Mitchell Kennerley in 1921.

Though it is unclear how finished Wilde may have considered this revision, it was published in a limited edition again under the title The Portrait of Mr W.H., and later in various Collected Works,[1] particularly including the Methuen edition in 1958, edited by Oscar Wilde’s younger son Vyvyan Holland. Later collections of Complete Works and Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories have also reprinted the Kennerley edition. Notably, Wilde researcher Ian Small edited an authoritative 2018 Oxford University Press edition (Volume VIII: The Short Fiction) that treats the Blackwood’s and the Rosenbach manuscript of the extended version separately, and this edition does much to elucidate Wilde’s revisions between the Blackwood’s version and the expanded manuscript. Unlike that scholarly edition, or former ones that have printed one version or the other, this COVE edition uses the very popular Kennerley edition as a base text and deploys digital capabilities and annotations to directly compare this Kennerley edition with the Rosenbach manuscript. In this way, we hope to illuminate Kennerley’s editorial interventions as a stage in the evolution of how the expanded version of The Portrait of Mr W.H. came to be in the popular eye.

“The Portrait of Mr W.H.” is about an attempt to uncover the identity of Mr W.H., the enigmatic dedicatee of Shakespeare's Sonnets. What is revealed is based on an unsubstantiated theory, originated by Thomas Tyrwhitt (1730-1786) and championed in this text by the tragic figure of Cyril Graham, and it is that the Sonnets were addressed to one Willie Hughes, portrayed in the story as a boy actor who specialised in playing women in Shakespeare's company. This theory depends on the assumption that the dedicatee is also the Fair Youth who is the romantic subject of most of the poems. The only “evidence” for this theory is the text of a number of sonnets such as Sonnet 20, that makes puns on the words “Will” and “Hues.”

This theory of Shakespeare’s Sonnets is embedded within a frame narrative, and in this way it is recounted by three men: the unnamed narrator, his friend Erskine, and, as an absent presence, Cyril Graham. Their role in this story is akin to Hamlet’s Horatio because they have been bequeathed the memory of Cyril Graham and his theory of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Thus, their lives become consumed by a desire to tell both Shakespeare’s love story and to testify to Graham’s passionate belief in that narrative. Within this narrative are contained complex meditations on the nature of art, desire, and truth. In all its versions, “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” is an extremely difficult work to classify: it could be said to be a novella, a critical essay, or perhaps a mash-up of detective and homoerotic love story tinged with Gothic undertones. The reality is that it is a text that contains a myriad of genres within its pages in a strikingly modern example of trans-generic textuality.

Textual History and Condition

As a lover of the arts and dramatist himself, Wilde had a long-standing appreciation of Shakespeare. He wrote several articles reviewing Shakespeare plays and making bold claims about Shakespeare’s attitudes and intentions as an artist. In his March 1885 essay “Shakespeare on Scenery” in Dramatic Review, Wilde asserts that “it is not difficult to see what Shakespeare's attitude would be” in regard to the appreciation of quality stage design. Similarly, in his May 1885 essay “Shakespeare and Stage Costume” in The Nineteenth Century, which would later become the basis for “The Truth of Masks” (1891), Wilde argues that the importance of visual elements including sets and costuming are obvious to “anybody who cares to study Shakespeare’s method” (800).

These essays have connections to “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” not just because they contain some fairly overconfident claims about Shakespeare’s intentions but also in that they rely on a view of theatre as an art that marries the visual and the textual. In “W.H.,” the narrator takes the same position that theatre relies on “the truth of visible presentation on the stage” and puts Willie Hughes at the centre of this claim as its embodiment.

Though earlier essays and projects have likely influenced “W.H.,” it is unknown exactly when Wilde started this story. In his extensive historical research on the text, Horst Schroeder contends that it may have been completed between January and April 1889, and this is partly due to Wilde’s use of the name “Ouvry.” Since there is no known artist of this name, Schroeder hypothesizes that it is a misspelling of “Oudry,” a sixteenth century artist mentioned in connection with Clouet and featured at a much-lauded exhibition running from December 1888-April 1889 (10-11). Though this is certainly possible, it is worth noting that in all his corrections and revisions, Wilde did not correct this spelling, repeating it in his own hand in the Rosenbach revised manuscript. Additionally, in his letters Wilde mentions the story earlier than this in a way that suggests its near completeness (Jones 4, Frankel 35-36). In a letter likely to the business manager for New York Daily Tribune editor Whitelaw Reid tentatively dated October 1887 Wilde mentions, “I am writing another story at present, and should be very pleased to forward you advance proofs should you care to publish it. The story is connected with Shakespeare’s Sonnets” (“To an Unidentified Correspondent” 325). Since the Tribune had published “The Canterville Ghost” in March 1887 and he had sent editor Reid the proofs for “Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime” (“To Whitelaw Reid” 299), it seems plausible Wilde initially had some initial plans to publish “W.H.” with the Tribune and that he was further along in writing “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” in 1887 than has been previously surmised.

Spring of 1887 was also when Wilde took on the editorship of The Woman’s World and so it is possible that his tenure distracted him from making further progress on the story. Though Schroeder guesses that Wilde may have sent his story out to other publishers, in Wilde’s known letters, no more allusions to “W.H.” are made until April 1889, when Wilde writes to William Blackwood about its publication:

Dear Sir, I remember reading some interesting articles on Shakespeare’s Sonnets in Blackwood, and would be very pleased if you would care to publish a story on the subject of the Sonnets which I have written. It is called “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” and contains an entirely new view on the subject of the identity of the young man to whom the sonnets are addressed. I will ask you to return me the manuscript in case you decide not to publish it. Truly yours Oscar Wilde (“To William Blackwood” 398)

Wilde negotiated with Blackwood on the timing of the publication in the July issue and also in order to retain the copyright which would allow him to republish the story if he chose. Blackwood anticipated a positive reception of the story, telling Wilde that he would be “very disappointed if it does not excite considerable interest amongst the press critics, as the story is powerfully told, and the working out of the Shakespearean theory full of playful ingenuity” (Complete Letters 402 n1). Confident of positive reviews, Blackwood also sent out an advanced notice that was published by the Athenaeum and the Scotsman and placed “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” as the first story in the July issue.

Oscar Wilde. “The Portrait of Mr W. H.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. July 1889. No. 885, vol. 146. Courtesy of Rosenbach Library and Museum.

According to Horst Schroeder’s meticulous study of the story’s reception, William Blackwood was correct in his predictions. Critics largely praised the story and focused on its “ingenious” theory, questioning how much of it was actually fabricated with at least one reviewer marvelling “Is Mr. Wilde joking?” (The Guardian qtd. in Schroeder 19). Those who took issue with the story generally did so on the grounds of Wilde’s scholarship, with one reviewer calling it “flimsy” and the journal of the Shakespeare Society of New York describing it as “Callow and amiable chatter” (The Observer and Shakespeariana qtd. in Schroeder 15). Schroeder’s research on this reception overturns the claims of Frank Harris whose highly suspect biography of Wilde claims that “W.H.” “gave [Wilde’s] enemies for the first time the very weapon they wanted” (177).[2] To give Harris the best case possible, Schroeder points out the very few reviews that drew attention to the moral character of the subject matter, the romantic relationship of between Shakespeare and a boy actor, one review calling it “very unpleasant” (The World qtd. in Schroeder, Composition 14). Instead, it seems that most critics were concerned with the scholarly viability of the theory itself, almost wholly ignoring its substantial frame narrative and the homosexual subtext.

It is quite possible that Wilde had these reviews in mind when he worked on expanding the story. As soon as it was published, Wilde mentioned expanding it to William Blackwood, proposing:

What would you say to a dainty little volume of Mr W.H. by itself? I could add to it, as I have many more points to make, and have not yet tackled the problem of the “dark woman” at the end of the sonnets. The price should be not more than 5/-. This should, I think, sell fairly well. I could add about 3000 words to the story. (“To William Blackwood,” 10 July 1889 407)

When Wilde worked on his revision, he left many elements of the frame narrative untouched, choosing to focus instead on elaborating on the theory. His expansions particularly include accounting for the “dark woman” of the Sonnets as mentioned in his letter and philosophical digressions on the nature of love, friendship, desire, and art. As Ian Small notes, whereas the Blackwood’s version can be confidently labelled a story, the expanded version more greatly resembles an essay in the style of Pater’s “Imaginary Portraits” (Textual Identity 509). In his expanded version, Wilde also made several corrections of dates and subtly acknowledged that the theory was not his own, though he stopped short of naming Thomas Tyrwhitt as its originator: “To have discovered the true name of Mr W. H. was comparatively nothing: others might have done that, had perhaps done it: but to have discovered his profession was a revolution in criticism.” In this brief passage, Wilde seems to acknowledge Tyrwhitt only to rebuff the criticisms of his indebtedness. This minimization of his reliance on source material would be a practice that he follows in other works including “Pen, Pencil and Poison.”[3]

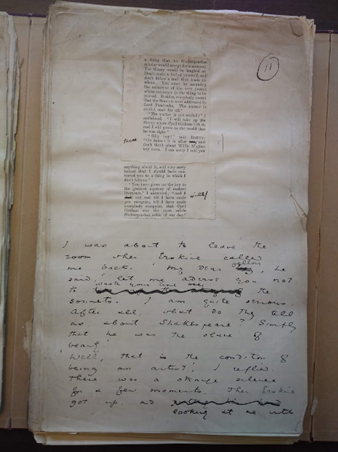

Oscar Wilde. “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” [expanded manuscript] p. 11.

Courtesy of the Rosenbach Museum and Library.

The only known expanded manuscript of “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” is held by the Rosenbach Library and Museum. It makes use of cut-and-paste pages with many handwritten annotations and corrections along with lengthy handwritten pages of additions that appear to be fair copy. On some pages, there are multiple cutouts from the Blackwood’s printing glued onto the page. In doing so, Wilde made use of at least two printed copies in order to use text originally printed on the verso side. The above example from folio 11 show a variety of the typical editorial markings and edits found in the manuscript: changes such as “shall” to “will” as well as lengthier additions or more significant edits that he handwrote on the same or on separate pages. Throughout, there are marginal annotations as well as whole pages of handwritten text. The notebook manuscript of “W.H.” also shows evidence of multiple phrases of revisions as some that were initially written on the opposite side of the pages were glued into the notebook, face down.

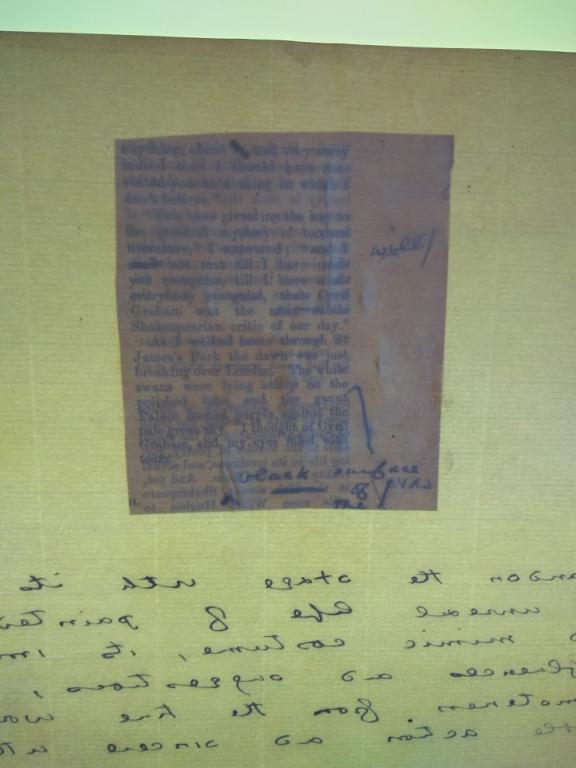

Oscar Wilde. “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” [expanded manuscript] p. 16. Courtesy of the Rosenbach Museum and Library.

The above image shows part of folio 16 of the enlarged manuscript of “Portrait of Mr W.H.” The page is reversed and shown over a lightbox revealing the words on the verso side of Wilde’s cutout. This cutout shows that Wilde made the same editorial choice as he did on folio 11 above by replacing “shall” with “will,” but that he decided to make further insertions of text on folio 11 before the closing paragraph. In this (presumably) prior revision he changes the Blackwood’s “The white swans were lying asleep on the polished lake, and the gaunt Palace looked purple against the pale-green sky” to “The white swans were lying asleep on the /black surface of the\ polished lake, and the gaunt Palace looked purple against the pale-green sky.” However, on folios 12 and 13 of the expanded version, Wilde later handwrote a more significant revision: “The white swans were lying asleep on the smooth surface of the polished lake, like white feathers fallen upon a mirror of black steel. The gaunt Palace looked purple against the pale-green sky, and in the garden of Stafford House the birds were just beginning to sing.”

Rather than the “dainty” 3,000-word addition that Wilde had proposed to Blackwood, Wilde’s expanded version adds about 14,000 words to the original 11,500-word story. Schroeder deduces that this version existed in some form by the autumn of 1889, but was likely not complete until 1891 or later (Composition 22-26). This theory is based on source material Wilde incorporated into the expanded version from an 1891 article by Brinsley Nicholson as well as earlier conversations between Wilde and the artist Charles Ricketts that show Wilde was considering themes and word choice that ended up in the manuscript.

Wilde spoke to Ricketts at length about his story because he had asked him to design the frontispiece to represent the forged portrait of Willie Hughes. Ricketts quickly complied and Wilde was so pleased with the result that he jested as if taking a role in his own story,

My dear Ricketts, It is not a forgery at all; it is an authentic Clouet of the highest artistic value. It is absurd of you and Shannon to try and take me in! As if I did not know the master’s touch, or was no judge of frames! (412).

The portrait itself, which was painted “upon a decaying piece of oak” constructed by Ricketts’s long-time partner Charles Shannon in order to effect authenticity, has since been lost, and only a thumbnail sketch remains.

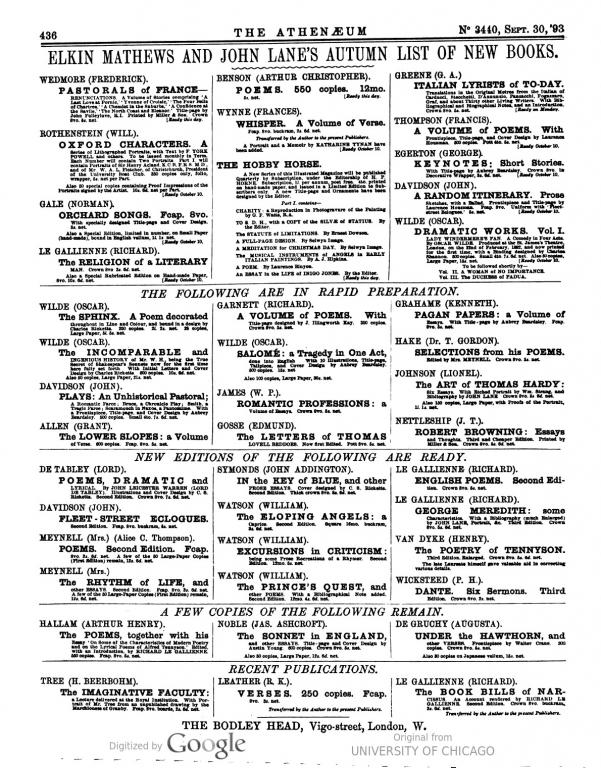

After this point, progress on the revised and expanded edition of “W.H.” seems to have stalled until May 1893 when Elkin Mathews and John Lane agreed to publish “W.H.,” along with several other works. They advertised the work as being “in rapid preparation” set with the following notice:

The Incomparable and Ingenious History of Mr. W.H., being the True Secret of Shakespear’s [sic] Sonnets now for the first time here fully set forth. With Initial Letters and Cover Design by Charles Ricketts. 500 copies. 10s. 6d. net. Also 50 copies, Large Paper, 21s. net. (436)

“Elkin Mathews and John Lane’s Autumn List of New Books.” Athenaeum, 30 September 1893, p. 436. Hathi Trust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.79233793&view=1up&seq=448

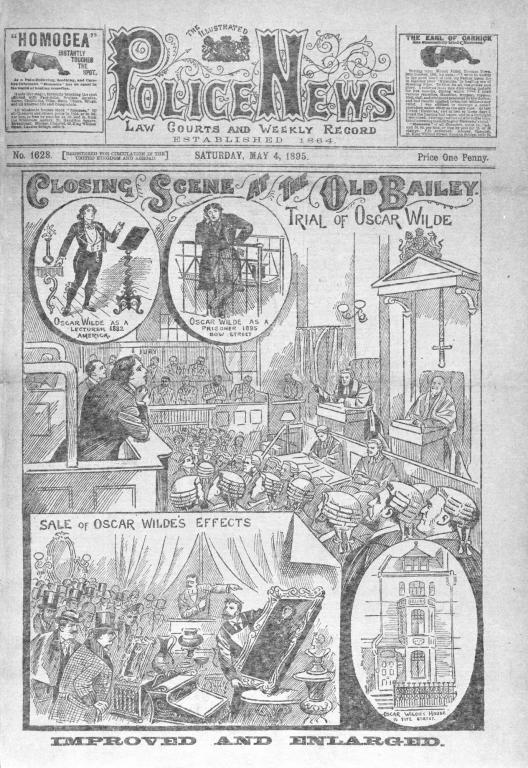

Though this notification was promising, “W.H.” was caught up in the dissolution of Mathews and Lane’s partnership soon after. Wilde was inclined to split his works between the publishers, but Mathews refused to publish “W.H.” “at any price” so it was given to Lane and may have been further delayed by Lane’s hesitancy and perhaps by its own unreadiness.[4] Wilde insisted on going ahead with publication, but before it could come to print, Wilde’s trials, arrest, and subsequent 1895 Tite street bankruptcy sale put a stop to future publication.

This sale resulted in the pillaging of Wilde’s manuscripts, books, notes, letters, gifts, artwork, and more, effectively scattering his personal effects across the world. There is record of Ricketts’s portrait being sold but it was subsequently lost, and the same fate was thought to have befallen the expanded manuscript of “W.H.” (Schroeder, Composition 34).

“Closing scene at the Old Bailey.” Illustrated Police News, 4 May 1895, London. British Library.

Schroeder notes that after Wilde’s imprisonment and the loss of his manuscript, the story “became part of the irretrievable past” to Wilde and he did not return to the project (Composition 34-35). However, in an 1899 letter to Oxford student Louis Wilkinson, much like his letter to Ricketts, Wilde again participates in the “W.H.” fantasy by gently urging Wilkinson to read his Blackwood’s story, as if enacting the part of Erskine initiating another to the Willie Hughes theory:

So you love Shakespeare’s Sonnets: I have loved them, as one should love all things, not wisely but too well. In an old Blackwood – of I fancy 1889 – you will find a story of mine called “The Portrait of Mr W. H.,” in which I have expressed a new theory about the wonderful lad whom Shakespeare so deeply loved. I think it was the boy who acted in his plays. If you come across the story, read it, and tell me what you think. (1133)

Thus, Wilde’s final known interaction with “W.H.” was in enacting a role in his own story, passing the theory on to another young man.

But this would not be the last the public would see of “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” In June 1921, it was announced that Mitchell Kennerley, a publisher and former employee of John Lane, had access to the expanded manuscript and would publish it in limited edition of 1,000 copies available to subscribers.

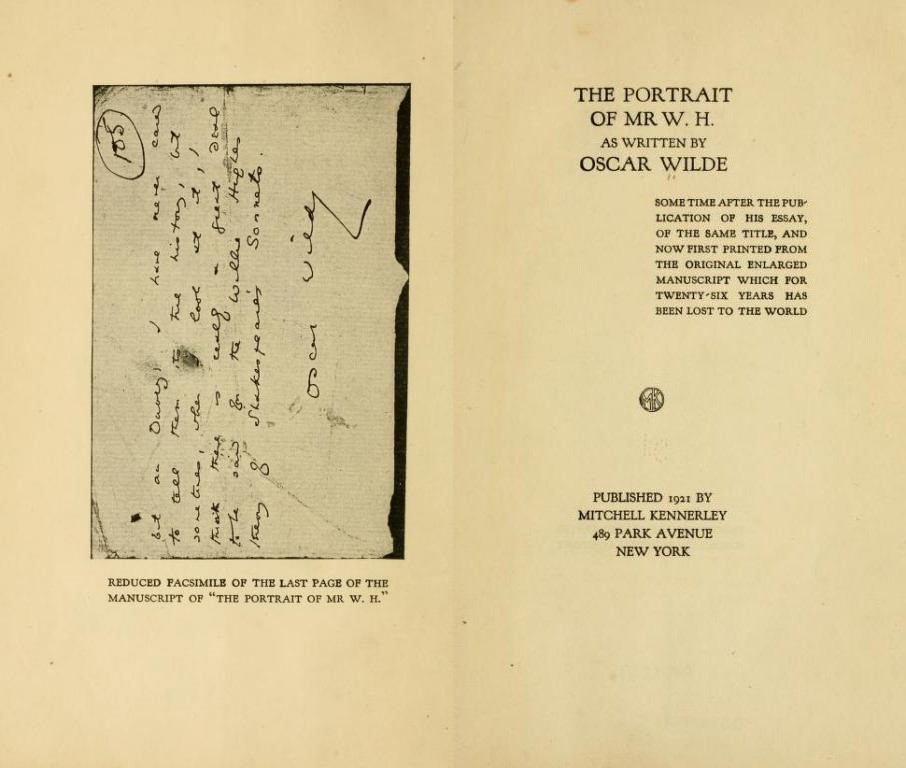

Oscar Wilde, The Portrait of Mr W. H. Kennerley, 1921. Internet Archive.

Instead of a rendition of the portrait of Willie Hughes as Wilde had planned with Ricketts, Kennerley published “W.H.” with the frontispiece of the final page of the Rosenbach manuscript containing Wilde’s signature. This perhaps acted as defence against scepticism since the manuscript was long thought entirely lost. However, reading Wilde’s authenticating signature as a substitute for fictional forgery tempts the scholar to interpret Kennerley’s efforts as ironic, or perhaps appropriate to the theme of the story as playing with the line between authenticity and forgery.

Kennerley’s explanation was that he had been given the manuscript by the sister of a deceased associate, whom he later identified as Frederic Chapman. Chapman, as former editor at Lane’s firm, Bodley Head, and recently deceased (1918) with a surviving sister, fits Kennerley’s account. Kennerley also apparently gave this sister the money from the sale of the manuscript to rare book collector and scholar Abraham Rosenbach (1876-1952), which further corroborates his claim. However, why the manuscript had lain dormant for so long has never been explained, and in the most complete account of the publication history of “W.H.” to date, Horst Schroeder wrote that he had “grave doubts” that Kennerley’s account is truly complete (Composition 38).

At the time of his publication of the expanded version of The Portrait of Mr W.H., Kennerley had published a number of authors that would become popular such as D.H. Lawrence and Edna St. Vincent Millay. No stranger to controversy, Kennerley had also gained some celebrity for a successful defence in the case United States v. Kennerley (1913), in which he was prosecuted for publishing Hagar Revelly, a novel that the prosecution alleged to be obscene for its portrayal of female sexuality.

Kennerley had a reputation for publishing controversial works not just because they were salacious, but also because he expressed genuine appreciation and excitement for them (Bruccoli). In an interview with the New York Evening Post, Kennerley called finding The Portrait of Mr W.H. “great fun” and “like having a million dollar bank note—It couldn’t be cashed” (“‘W.H.’ a Boy Actor, Wilde’s Theory” 7). However, the Wilde estate, then held by Vyvyan Holland and advised by Christopher Millard, was hesitant to allow publication, having understandable doubts that what Kennerley found was truly an expanded draft and not, perhaps, an earlier draft of the Blackwood’s version (Schroeder, Composition 40). The Times also made the presumption that Kennerley’s manuscript could not possibly be a revised manuscript and curiously claimed that the copy which “reached London” was less polished than the Blackwood’s version and made reference to it being entirely a holograph rather than “a set of Blackwood’s sheets with copious marginal additions” which, of course, the Rosenbach manuscript shows that it, in fact, is (“‘Mr W.H.’: A Missing Manuscript” 8).

These inconsistencies in the history of the manuscript as well as the fact that the Kennerley edition includes some material not found within the Rosenbach manuscript raises many questions. In his recent Oxford University Press edition of Wilde’s short fiction including both the Blackwood’s edition of “Portrait of Mr W.H.” and the expanded version, Ian Small suspects that “Kennerley had access to material which can now be presumed to be lost” (“Textual Introduction” cii). This theory is based on several factors. First, the motley character of the Rosenbach manuscript with some pages showing messy annotations while others in fair copy seem to indicate that it was “not in a state to be handed over to a publisher” (“Introduction” lxxix). Small indicates that Kennerley edited and sometimes over-edited the manuscript for consistency in punctuation, spelling, and phrasing.[5] Though this was mostly usual editorial practice at the time and Wilde’s punctuation was not typically consistent even in drafts of other works, the Rosenbach manuscript shows a number of irregularities in Wilde’s hand such as scored out page numbers, deleted repetitions in passages, and blank spaces to allow for pages to connect properly. The lack of uniformity in editing style and effort to connect pages could be interpreted as signs that the Rosenbach manuscript is actually formed from more than one draft.

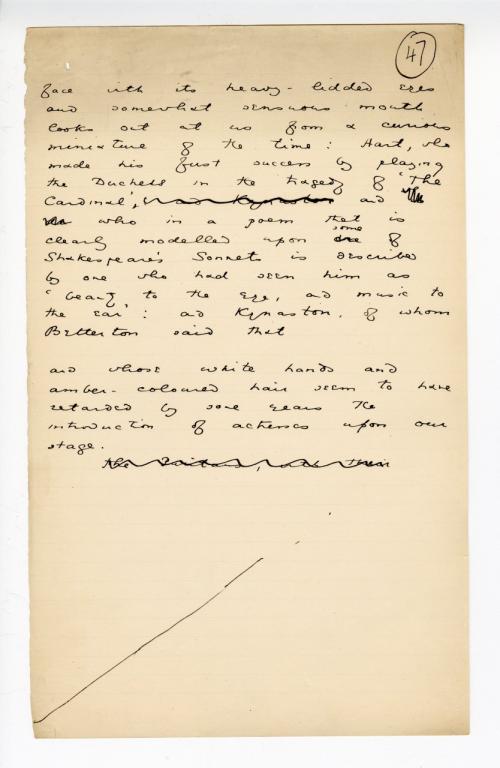

Furthermore, Wilde left several blanks in the Rosenbach manuscript that are supplied in the Kennerley edition. In particular, on folio 47 of the Rosenbach manuscript, Wilde attributes a source but leaves a blank for a quotation, presumably to be filled in at a later date when he would have access to the source: “…and Kynaston of whom Betterton said that [Wilde skips a line here] and whose white hands and amber-coloured hair seem to have retarded by some years the introduction of actresses upon our stage.”

Oscar Wilde. “The Portrait of Mr W.H.” [expanded manuscript] p. 47. Courtesy of the Rosenbach Museum and Library.

Kennerley’s edition seamlessly supplies this quotation: “and Kynaston, of whom Betterton said that ‘it has been disputed among the judicious, whether any woman could have more sensibly touched the passions,’ and whose white hands and amber-coloured hair seem to have retarded by some years the introduction of actresses upon our stage” (74). However, the problem is that this quotation is not actually from Betterton at all, but John Downes (Small “Introduction” lxxxi). As Small reasons,

The fact that he failed to attribute it correctly suggests that he was not working from primary sources nor, more specifically, from Downes’s work. If he had consulted Betterton, he would have known the quotation was a fiction; if, however, he had been working from Downes’s Roscius Anglicanus he would have known that Wilde's attribution was erroneous. So what text could he have been working from? (lxxxi).

Small asserts that Kennerley’s additions such as this indicate that he must have been working from additional source material not included in the Rosenbach manuscript that are now lost. Thus, though the long-lost expanded version of Portrait of Mr W.H. has been found and reprinted, there are still many mysteries that surround it. For a story that deals in many ways with textual mysteries and overreaching scholarly intervention, perhaps this is only appropriate.

The current COVE edition of The Portrait of Mr W.H. makes use of Mitchell Kennerley’s 1921 printing as the base copy text. Accordingly, it follows many subsequent reprintings. Where this version distinguishes itself is in indicating various places that Kennerley’s text differs from Wilde’s editorial changes according to the manuscript held by the Rosenbach Library and Museum. In this way, we hope that it can be seen as a dynamic text, one that evolved even after Wilde’s lifetime.

Wildean Textuality and Aesthetics

The Portrait of Mr W.H. can be read as a valuable encapsulation of some of the major themes and ideas contained within Wilde’s literary corpus. In the opening section of the work, for example, our unnamed narrator is having a discussion with Erskine about literary forgeries and he makes the following assertion:

[W]e had no right to quarrel with an artist for the conditions under which he chooses to present his work; and that all Art being to a certain degree a mode of acting, an attempt to realise one’s own personality on some imaginative plane out of reach of the trammelling accidents and limitations of real life, to censure an artist for a forgery was to confuse an ethical with an aesthetical problem.

This conception of art as separate from life and absolved from any need to imitate reality is obviously a key feature of Wilde’s aesthetic theory and one which derives strongly from the work of Walter Pater, one of Wilde’s great heroes.

In Wilde’s dialogue “The Critic as Artist,” a similar observation about the relationship between art and reality to that posited above is also to be found: “To give an accurate description of what has never occurred is not merely the proper occupation of the historian, but the inalienable privilege of any man of parts and culture” (1114). When Cyril Graham commissions a forged picture in order to make Erskine believe in the Willie Hughes theory, it is because he believes that lying in art can be put into the service of a greater Truth, one that is divorced from reality. As Graham says to Erskine: “I did it purely for your sake. You would not be convinced in any other way. It does not affect the truth of the theory.”

Wilde’s belief in artistic language as a vehicle for telling “beautiful untrue things” has been attributed by some to his Irish heritage because of Ireland’s colonial relationship to the English tongue which her people were forced to adopt as a first, but never native, language. As Declan Kiberd argues: “The modern distrust of styles and disenchantment with language itself are both strong in Irish writing, if only because of the artists’ awareness that whenever they use English they are not writing in their own language. Irish people are keenly aware that certain words and phrases have one meaning in Ireland and another in England” (277). Wilde’s relationship to modern literature can be interpreted as being inextricably bound up with his relationship to his country of birth.

Danny Osborne, sculptor. Statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, 1997.

Photograph by Stéphane Moussie, 2010. Wikimedia Commons.

As a central concern of The Portrait of Mr W.H., the topic of forgery was also one that was of great personal interest to Wilde in relation to his Irish background: As part of the British Tory party’s efforts to discredit the leader of the Irish Home Rule Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, The Times had published the facsimile of a letter, purportedly from Parnell, in which he could be said to be almost inciting violence in Ireland. Parnell denounced this document as a forgery and, as a result of demands from Parnell himself, a special commission was established to investigate this issue and several other accusations against the Home Rule leadership. Wilde was frequently in attendance during Parnell’s testimony in front of this committee. This piece of biographical information further links Wilde’s Irish heritage and political leanings to the literary endeavour that was The Portrait of Mr W.H.[6]

The Portrait of Mr W.H. is also an important precursor to Wilde’s (in)famous novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Like W.H., Wilde would later revise Picture of Dorian Gray from a shorter to a lengthier version. Thematically, they both also deal with the interfaces between art and identity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the description of the portraits at the beginning of both works are strikingly similar:

It was a full-length portrait of a young man in late sixteenth-century costume, standing by a table, with his right hand resting on an open book. He seemed about seventeen years of age, and was of quite extraordinary personal beauty, though evidently somewhat effeminate. Indeed, had it not been for the dress and the closely cropped hair, one would have said that the face with its dreamy wistful eyes, and its delicate scarlet lips, was the face of a girl.

The linguistic depiction of the portrait as of a man “of extraordinary personal beauty” is replicated by Wilde at the beginning of his only novel to describe Dorian Gray as he appears in Basil Hallward’s picture (18). Later, Dorian Gray is also described as having similar personal features to Mr. W.H.: “his finely curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair” (27).

Cyril Graham’s childhood, as mediated to readers by Erskine, is also very similar to what we learn about Dorian Gray’s parents and, also, his relationship with his grandfather: “I don’t think that Lord Crediton cared very much for Cyril. He had never really forgiven his daughter for marrying a man who had not a title [….] Cyril had very little affection for him, and was only too glad to spend most of his holidays with us in Scotland. They never really got on together at all. Cyril thought him a bear, and he thought Cyril effeminate.” The absence of adequate parental authority is often used in Wilde’s texts to symbolise a character’s opportunity and capacity for self-development and personal creation without the overarching influence of the “law of the father.” The issue of identity as a fluid matter of style and surface appearances is also prevalent in both The Portrait of Mr W.H. and The Picture of Dorian Gray. As Neil Sammells argues: “Identity [in ‘The Portrait of Mr W.H.’] is thus seen in terms of surface, fluctuation, dispersal, rather than depth, stability and integration. The mirror-image [of Mr W.H.’s portrait] anticipates those which Wilde uses to affirm Dorian’s growing recognition of his polymorphous self as it is multiplied through sensation” (57).

Bildungsroman/Kunstleroman

Although The Portrait of Mr W.H. cannot be considered a novel (partly for reasons of length), it does share many of the traits of both a bildungsroman (coming of age novel) and a kunstleroman (becoming an artist novel). Thus, it is a text that anticipates by nearly thirty years James Joyce’s innovative treatment of both of these literary genres in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). By not providing the narrator of “W.H.” with a name, the text suggests a certain degree of provisionality in his subjectivity. In many respects, this narrator is shaped, both personally and, at least in part, artistically, by the story of Willie Hughes and by Cyril Graham and Erskine who decided of their volition to take on the role of caretakers of Hughes’ memory.

The narrator also comes to a Romantic appreciation of the value of what Martin Heidegger calls “average everydayness” in art:

The great events of life often leave one unmoved; they pass out of consciousness, and when one thinks of them, become unreal. Even the scarlet flowers of passion seem to grow in the same meadow as the poppies of oblivion. We regret the burden of their memory, and have anodynes against them. But the little things, the things of no moment, remain with us. In some tiny ivory cell the brain stores the most delicate, and the most fleeting impressions. (422)

The message that is contained in this passage is also one that is to be found in a standard bildungsroman where stories of everyday personal experience and development are privileged over the grander narratives associated with epic literature.

As he delves further into the theory of Shakespeare’s and Willie Hughes’ relationship, the narrator begins to feel that this story and his role as one of its tellers is impacting his external and internal existences: “Art, as so often happens, had taken the place of personal experience. I felt as if I had been initiated into the secret of that passionate friendship, that love of beauty and beauty of love […] of which the Sonnets, in their noblest and purest significance, may be held to be the perfect expression.” The story that was emerging for him via a bravura piece of performative close-textual analysis of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, also affects his sense of self and soul: “A book of sonnets, published nearly three hundred years ago, written by a dead hand and in honour of a dead youth, had suddenly explained to me the whole story of my soul’s romance.” As can very often happen when an artist creates a compelling literary presence, the narrator begins to develop a powerful personal relationship with the spectral figure of Willie Hughes. For the narrator: “Willie Hughes became to me a kind of spiritual presence, an ever-dominant personality.”

During his close readings of the Sonnets, the narrator falls into constructing the story that he imagines to represent the connected lives of Shakespeare and Willie and the love that emerged between them. In our narrator’s hands, the story of their love becomes one that involves passion and jealousy as the so-called “dark lady” causes a rift between Shakespeare and Willie Hughes which disrupts their amorous passions and also provokes Shakespeare to experience certain feelings of desire for the dark lady: “He [Shakespeare] had his moments of loathing for her, for, not content with enslaving the soul of Shakespeare, she seems to have sought to snare the senses of Willie Hughes [….] Then he sees her as she really is, the ‘bay where all men ride.’” In passages such as this, the narrator of The Portrait of Mr W.H. is no longer relating a speculative analysis of the Sonnets; he is telling a story in a style that is akin to a narrative that one would find in an artistic text as opposed to an academic piece of analysis.

The narrator refuses to follow the rules of artistic inspiration and creation when he begins to demand that this tale of Shakespeare, Willie Hughes, and the dark lady, be subject to factual verification. By so doing, he does not allow the story to remain a beautifully constructed tale that should be allowed to exist—as Cyril Graham wished—as a lyrical and stylistically sophisticated text that was not shackled to fact, reality, or realism. For this reason, when the narrator began to believe that this story might have actually happened in the historical past, it begins to lose its power and he becomes disenchanted with the tale that he had masterfully created. When he returns the Sonnets: “They gave me back nothing of the feeling that I had brought to them; they revealed to me nothing of what I had found hidden in their lines.” For this reason, the narrator fails to come of age as an artist in this example of kunstleroman.

Ultimately, it is in the character of Cyril Graham that The Portrait of Mr W.H. produces the perfect example of an artist figure. Cyril Graham’s theory of Shakespeare’s Sonnets and the love affair between Shakespeare and Willie Hughes that is narrated through Graham’s textual analysis of the poems represents a perfect example of the “highest Criticism” as described in “The Critic as Artist”:

[…]the highest Criticism, being the purest form of personal impression, is in its way more creative than creation, as it has least reference to any standard external to itself, and is, in fact, its own reason for existing, and, as the Greeks would put it, in itself, and to itself, an end. Certainly, it is never trammelled by any shackles of verisimilitude” (1125).

Graham’s theory of Willie Hughes operates under this model of criticism as art held to the standards not of fact and accuracy but of subjective beauty. Graham’s influence over his friend Erskine can also be interpreted as that between an artist and his sometimes disciple. Following his hearing of the theory, Erskine experiences a moment of epiphanic insight that is associated with compellingly creative art: “Of course I was converted at once, and Willie Hughes became to me as real a person as Shakespeare.” Unlike Cyril Graham, who does not desire to have the theory corroborated with reference to facts, both Erskine and the unnamed narrator attempt to prove that Willie Hughes was a real person and these efforts towards verisimilitude do violence to the artistic quality of the story that Graham created.

According to Erskine, Graham was very annoyed by Erskine’s “philistine tone of mind.” Graham did not wish for his beautifully constructed love story to be sullied by demands for evidence or realism. Graham’s commissioning of a forged portrait of Willie Hughes represents an attempt on his part to place this figure outside the realm of reality and into that of performative, creative, and unreal art. Cyril Graham also inserts himself into this tragic love story of Shakespeare and the boy actor Willie Hughes by committing suicide as a gesture of his belief in this artistically created theory of the Sonnets. By doing so, Graham casts himself in the role of a tragic disciple and willing martyr to artistry. Graham’s suicide has such a profound influence on Erskine that, when Erskine realises that he is dying of a lingering illness, he sends a letter to the narrator pretending that he is also going to follow Graham’s dramatic example and commit suicide: “I still believe in Willie Hughes; and by the time you receive this, I shall have died by my own hand for Willie Hughes’ sake: for his sake, and for the sake of Cyril Graham, whom I drove to his death by my shallow scepticism and ignorant lack of faith.” Because of the influence that he exerts on the lives and destinies of either real or imagined others, Cyril Graham can thus be viewed as the Wildean “critic as artist” par excellence.

It is never known whether Graham ever actually believed in his theory of Shakespeare’s Sonnets or whether he, like the critic in Wilde’s “The Truth of Masks,” ultimately disagreed with the central thesis that he proposed (1173). However, the question of whether or not he believed in the theory is outside of the narrative scope of The Portrait of Mr W.H. The actual belief in the factual accuracy of this theory would subordinate aesthetics to reality and, like Wilde, Cyril Graham almost certainly believed that the story he developed out of his reading of Shakespeare’s Sonnets was more a work of art than of criticism. Thus, Graham can be regarded as a partial version of Wilde himself. Though Wilde seems to have subscribed to the theory at points in his letters with Ricketts and others, it isn’t clear if his motives are ultimately critical or aesthetic.[7]

Shakespeare, Wilde, and Queer Desire

Although The Picture of Dorian Gray is the work most associated with the epochal “Wilde Trials” that culminated in Wilde being sentenced to two years hard labour between 1895-1897 for the crime of “acts of gross indecency between men,” The Portrait of Mr W.H. is equally prescient in terms of Wilde’s representation of male same-sex desire. As Matthew Sturgis argues in relation to W.H., “Wilde’s vision was to connect Shakespeare to the Greek tradition of pederastic love as it had been rediscovered in the Renaissance. In the ‘curious dedication’ that Shakespeare had inscribed to ‘Mr W.H.’ as the ‘onlie Begetter’ of his sonnets, Wilde detected the note of Pure Platonism” (381).

In the second of his three 1895 trials, Wilde famously defended what his lover Lord Alfred Douglas had poetically termed “the love that dare not speak its name” in terms that call to mind the love between Shakespeare and Willie Hughes in “W.H.”: “‘The Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect” (qtd. in Ellmann 435). This defence of “platonic love” was one that Wilde had expounded in far greater length in the protean text that is The Portrait of Mr W.H. and, in particular, in the expanded version. As Ian Small notes in a reflection on his scholarly edition of the text, Wilde’s additions in the expanded version, “reveal a significant change in Wilde’s conception of the work, for they contain his attempt to contextualize, intellectualize, and aestheticize Shakespeare’s attitude to Willie Hughes, and to locate Shakespeare’s supposed feelings for Hughes in a tradition of male-male desire exhibited in the lives of artists and writers of the Italian Renaissance” (Textual Identity 521). Wilde effects these changes partly by relying on further references and connections to Plato, Michelangelo, and Montaigne, but also, Small claims, by moving “emotional centre” of the narrative to the essay-like analysis of the Sonnets over the frame story between the unnamed narrator, Erskine, and Cyril (522).

Both versions deal with Shakespeare’s homosexual relationship with Mr. W.H. and how this relationship positively affected his development as an artist. In a wonderfully allusive passage, Wilde writes about the influence Willie Hughes had not only on Shakespeare’s heart, but—in a poetic mash-up of allusions to the Sonnets—also on his art:

[W]ho else but he [Hughes] could have been the master-mistress of Shakespeare’s passion, the lord of his love to whom he was bound in vassalage, the delicate minion of pleasure, the rose of the whole world, the herald of the spring, decked in the proud livery of youth, the lovely boy whom it was sweet music to hear, and whose beauty was the very raiment of Shakespeare’s heart, as it was the keystone of his dramatic power?

The vision of homosexual love modelled by Shakespeare and Hughes is not only muse-like inspiration, but also artistic collaboration, which was far more valuable to Wilde and matches his description of that “love that dare not speak its name,” further described in the trial as “intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him” (qtd. in Ellmann 435). Even more so in the expanded version, Willie Hughes and William Shakespeare are hypothesized by the narrator to have that sort of generative love of the lover and beloved that features in the Greek and Renaissance traditions.

This relationship between Shakespeare and Willie Hughes is paralleled in the relationship between the older Erskine and the younger narrator, who attempts to reawaken and embody Cyril’s passion. In this shorter version of the text, there are fewer scholarly details, putting the focus on the narrator’s impressions of the evidence over the evidence itself, and the story revolves around the narrator’s relationship to the theory and to Erskine. As in Dorian Gray, there is the implication of seduction in the influence that the more experienced man exerts over the younger. Erskine may not be actively trying to seduce the narrator; nevertheless, he presents the theory in a seductive manner, allowing a quick gaze at the mysterious picture, describing its history, and then warning him off with the prescient, “You will break your heart over it.” In both versions, the narrator describes his enchantment with the theory in terms more suited to a physical romance. Though he attempts to discover evidence, his acceptance of it is entirely emotional. In the beginning of his research he describes his feelings as that he had his “hand upon Shakespeare’s heart, and was counting each separate throb and pulse of passion.” After writing a note to Erskine, he loses all interest in the theory, reasoning that, “Perhaps, by finding perfect expression for a passion, I had exhausted the passion itself.” Like a fatigued lover, the narrator loses romantic interest and his initial infatuation in the theory has been sated.

In the expanded version, Wilde does add a few details to the narrator’s reflections that overtly label his relationship with the theory a “great romance”; however, most of the added details are instead central to the literary analysis. The formerly the central narrative arc becomes a frame story in the expanded version. In this regard, several scholars including Ian Small and Geoff Dibb have hesitated to call these different “versions” of the same story, suspecting instead that they should be considered separate texts altogether (Small “Textual Identity” 510; Dibb “Incomparable” 105).

The longer version not only augments the details of the relationship between Shakespeare and Hughes, but implicates the reader in a sort of game of seduction that Kostas Boyiopoulos labels a “long con” (598). According to Boyiopoulos, the narrator’s attraction to the theory of Willie Hughes also, “reaches for the reader, the second target, past the narrator. The reader’s mind is beleaguered by the nagging suggestion that the Willie Hughes hypothesis as a beautiful lie is not necessarily to be corroborated but legitimized” (608). This seduction might also be extended to the evolution of the text, that the “emotional centre” was shifted from the frame narrative to the essay-portion of the text. As discussed, reviewers at the time that Wilde published the Blackwood’s version were primarily interested in the Shakespearean scholarship. Thus, by expanding the scholarship, Wilde was at least partly responding to the desires of his audience. By being presented with the facts in as much detail as the unnamed narrator (who may be unnamed partly as a proxy for readers), readers may also participate in the discovery process and assess the evidence for themselves. By and large, Wilde accurately presented the text and historical information given in the text; however, as the theory has no falsifiable evidence based in reality, it relies wholly on its ability to charm the reader. The text’s privileging of art’s active revolt against realism has also been linked by Lawrence Danson to Wilde’s non-normative sexual preferences: “To Wilde, realism is on the wrong side of a divide which separates imitation from creation, nature from form, life from art, realism from romance, and a supposedly ‘natural’ sexuality from a sexuality which, like art, disdains any attempt to dictate limits” (87).

The Portrait of Mr W.H. is also notable for a passage in which Wilde has his narrator speak of theatre’s power to highlight the performative nature of gender roles as they are defined in specific social contexts:

To say that only women can portray the passions of a woman, and that therefore no boy can play Rosalind, is to rob the art of acting of all claim to objectivity, and to assign to the mere accident of sex what properly belongs to imaginative insight and creative energy. Indeed, if sex be an element in artistic creation, it might rather be urged that the delightful combination of wit and romance which characterises so many of Shakespeare’s heroines was at least occasioned if not actually caused by the fact that the players of these parts were lads and young men, whose passionate purity, quick mobile fancy, and healthy freedom from sentimentality can hardly fail to have suggested a new and delightful type of girlhood or of womanhood.

This quote anticipates by almost a hundred years Judith Butler’s epochal essay, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” which was published in 1988—significantly in a journal of theatre of studies—in which Butler first outlined her by now famous theory concerning the performatively constituted nature of gender norms. This essay would then evolve into one of Butler’s most celebrated and discussed texts, Gender Trouble (1990), which is credited as being one of the textual catalysts for the rise of the school(s) of thought known as Queer Theory. Thus, The Portrait of Mr W.H. can be regarded as a theoretical text that anticipates one of the most influential strands of contemporary cultural criticism.

A Wild(e) Man for Our Times

The quotation that opened this introduction concerning the idea that life and reality is mediated to us by a series of representations (what Georg Wilhelm Hegel—a thinker whose work Wilde admired—would call “picture thinking”[8]) is a neat encapsulation of how The Portrait of Mr W.H. might be understood as—among many other things—a proto-postmodernist text. According to Fredric Jameson’s influential definition, a postmodern world can be defined, at least in part, as one of an “absolute and absolutely random pluralism . . . a coexistence not even of multiple and alternate worlds so much as of unrelated fuzzy sets and semiautonomous subsystems” (372). These subsystems can also be described as a series of representative artefacts, cultures, and objects that unsuccessfully pose as (to use one of Wilde’s least favourite words) “natural.” Whilst modernism as a movement still allowed for itself a belief in a coherent and stable world that could be represented as such via artistic representations, postmodernism revelled in the void of reality and stability that it regarded as symptomatic of its contemporary moment. In “Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime,” Wilde painted a picture of existence that anticipates postmodern attitudes towards identity and subject formation: “Most men and women are forced to perform parts for which they have no qualifications. Our Guildensterns play Hamlet for us, and our Hamlets have to jest like Prince Hal. The world is a stage, but the play is badly cast” (165). This diagnosis of life as a series of artificial and inauthentic roles cuts to the heart of postmodernity and its acceptance of constructed superficiality as being at the core of what is held by some to be the “natural world.”

This postmodern vision of what being in the world entails is also present in The Portrait of Mr W.H. The literary structure of W.H.—in which the love story of William Shakespeare and Willie Hughes is constructed and then told to greater and lesser extents by three narrators who cannot be regarded as being reliable—also relates to the preoccupation with narrative, its nature and its limitations, which Rudiger Imhoff correctly points to as being a pressing concern of postmodernism (15).

The concluding paragraph of W.H. strikes an authentically inauthentic postmodern note concerning the ultimate fate of the titular portrait:

This curious work hangs now in my library, where it is very much admired by my artistic friends, one of whom has etched it for me. They have decided that it is not a Clouet, but an Ouvry. I have never cared to tell them its true history, but sometimes, when I look at it, I think there is really a great deal to be said for the Willie Hughes theory of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

As Ruth Robbins argues: “It is as if the evidence evinced by the acknowledged forgery still has some claim to authenticity, for, if the fake has real effects, it may indeed be more potent than a genuine artefact. The story’s oscillation between faith and doubt is dramatized in that final statement which negates any firm conclusion” (107). It is arguable that postmodernity conceives of life as a series of forgeries that attempt, with varying degrees of success, to masquerade as being real, natural, and immutable; whereas, in actuality, the opposite is precisely the case and that is the impression of the world that The Portrait of Mr W.H. wishes to leave in its closing lines. The fact that we do not know whether Ouvry is a misspelling of Oudry or is a fabricated artist, adds yet another layer of ambiguity and dubious evidence. If, as Richard Ellmann argues, modernity, postmodernity, and the contemporary moment have inherited Oscar Wilde’s struggle to “achieve supreme fictions in art” (553), then The Portrait of Mr W.H. is a prime example of the “modern/postmodern Oscar Wilde” being laid bare in his writing and aesthetical vision.

Works Cited (Criticism)

Butler, Judith. “Performative Act and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, December 1988, pp. 519-531.

Boyiopoulos, Kostas. “Oscar Wilde and the Confidence Trick.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 26, no. 4, Oct. 2021, pp. 596–610.

Bruccoli, Matthew J. The Fortunes of Mitchell Kennerley, Bookman. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986.

Danson, Lawrence. “Wilde as critic and theorist.” The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde, edited by Peter Raby. Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 80-95.

---. Wilde’s Intentions: The Artist in His Criticism. Clarendon, 1997.

Dibb, Geoff. “The Incomparable and Ingenious History of Mr Cyril Graham, now for the First Time Here Fully Set Forth A Study in Green (Park).” The Wildean. no. 50, Jan. 2017, p. 104-119.

---. “The Portrait(s) of Mr. W.H.” Charles Ricketts & Charles Shannon edited by Paul van Capelleveen, November 13, 2019, http://charlesricketts.blogspot.com/2019/11/433-portraits-of-wh.html

Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. Penguin Books, 1988.

Frankel, Nicholas, editor. “A Note on the Texts.” The Short Stories of Oscar Wilde: An Annotated Selection. Harvard UP, 2020.

Guy, Josephine, editor. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Volume 4: Criticism. Oxford UP, 2007.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time, translated by John MacQuarrie and Edward Robinson, Blackwell Publishing, 1962.

Imhoff, Rudiger. The Modern Irish Novel: Irish Novelists after 1945. Wolfhound Press, 2002.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke UP, 1989.

Jones, Rebecca E., Catching All Passions in His Craft of Will: Portraits and Pater in Oscar Wilde’s “The Portrait of Mr W. H.” 2016. Virginia Commonwealth University, Thesis. p.4. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5212&context...

Kiberd, Declan. “Oscar Wilde: The Resurgence of Lying.” The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde, edited by Peter Raby. Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 276-294.

Knight, Wilson. The Mutual Flame: On Shakespeare's Sonnets and the Phoenix and the Turtle. Methuen, 1955.

Lange, Robert J.G. “The provenance of Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Portrait of Mr. W.H.’: an oversight?” Notes and Queries, vol. 42, no. 2, 1995, p. 202. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A17281363/AONE?u=temple_main&sid=AONE&xid=3bba198c. Accessed 25 May 2021.

Robbins, Ruth. Oscar Wilde. Continuum, 2011.

Sammells, Neil. Wilde Style: The Plays and Prose of Oscar Wilde. Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

Schroeder, Horst. Annotations to Oscar Wilde, the Portrait of Mr. W.H. Technische Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, 1986.

---. Oscar Wilde, The Portrait of Mr. W.H.—Its Composition, Publication, and Reception. Technische Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, 1984.

Sloan, John. “‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.’ The Rosenbach Manuscript Examined.” The Wildean, no. 51, July 2017, pp. 37-44.

Small, Ian., editor. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 8: The Short Fiction. Oxford University Press, 2017.

---. “‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.,’ Textual Identity, and Oscar Wilde’s ‘Incalculable Injury.’” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 63, no. 4, 2020, pp. 509-532.

Sturgis, Matthew. Oscar: A Life. Zeus Ltd., 2018.

Wright, Thomas. Oscar’s Books: A Journey Around the Library of Oscar Wilde. Vintage, 2009.

Primary Sources

Collier, John Payne. The History of English Dramatic Poetry to the Time of Shakespeare and Annals of the Stage to the Restoration. 3 vols. 1831.

“Closing scene at the Old Bailey.” Illustrated Police News, 4 May 1895, London. British Library. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/closing-scene-at-the-old-bailey-newspaper-coverage-of-the-oscar-wilde-trial

Douglas, Alfred. The True History of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. M. Secker, 1933.

Dowden, Edward. Shakespeare: A Critical Study of his Mind and Art. The Sonnets, 3rd edition. Harper, 1881.

“Elkin Mathews and John Lane’s Autumn List of New Books.” Athenaeum, 30 September 1893, p. 436. Hathi Trust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.79233793&view=1up&seq=448

Harris, Frank. Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions, vol. 1, 1916. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16894/16894-h/16894-h.htm

Nicholson, Brinsley. “Was Mr. W. H. the Earl of Pembroke?” Athenaeum, 11 July 1891, p. 74-75. Hathi Trust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.l0073150088&view=1up&seq=97

“‘Mr W.H.’: A Missing Manuscript.” The Times, 18 June 1921, p. 8. The Times Digital Archive. Gale.

Massey, Gerald. Shakspeare’s Sonnets Never Before Interpreted. Longmans, 1866.

Osborne, Danny, sculptor. Statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, 1997. photograph by Stéphane Moussie, 2010. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59074027

Pater, Walter. Imaginary Portraits. 1887.

Ricketts, Charles. Oscar Wilde: Recollections. Nonesuch Press, 1932.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. A Study of Shakespeare. Chatto, 1880.

Symonds, John Addington. The Renaissance in Italy. vol. 3. Smith, 1899.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Critic as Artist.” Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, edited by Merlin Holland, Collins, 2003, p. 1108-1155.

---. Oscar Wilde, “Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime.” Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, edited by Merlin Holland, Collins, 2003, p. 160-183.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, edited by Merlin Holland, Collins, 2003, pp. 17-159.

---. “The Truth of Masks.” Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, edited by Merlin Holland, Collins, 2003, p. 1156-1173.

---. “To Charles Ricketts.” Autumn 1889. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 412.

---. “To an Unidentified Correspondent.” October 1887. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 325.

---. “To Louis Wilkinson.” 20 March 1899. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 1133.

---. “To William Blackwood.” April 1889. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 398.

---. “To William Blackwood.” 10 July 1889. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 407.

---. “To Whitelaw Reid.” Late April 1887. Complete Letters, edited by Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Henry Holt, 2000, p. 299.

---. “The Portrait of Mr W. H.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. July 1889. No. 885, vol.

---. The Portrait of Mr W. H. [Manuscript]. Rosenbach Library and Museum.

---. The Portrait of Mr W. H. Kennerley, 1921. Internet Archive.

---. “Shakespeare on Scenery.” Dramatic Review, March 14, 1885.

---. “Shakespeare and Stage Costume.” The Nineteenth Century, May 1885, pp. 800-818.

“‘W. H.’ a Boy Actor, Wilde’s Theory,” New York Post, 20 June 1921, p. 7.

Notes

[1] Though it was formerly thought that Methuen provided the first edition to the general public, Robert J. G. Lange’s 1995 research notes that the 1923 Doubleday, Page & Co Complete Works and William H. Wise & Company's Connoisseur's edition in 1927 reprint the Kennerley edition as well.

[2] It is worth noting that even though the volume of Harris’s Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions appears as “published by the author” on the title page, Mitchell Kennerley set it in type and had the book manufactured at cost. This biography contains many stories that are widely recognized as complete fabrications. See Matthew Bruccoli, The fortunes of Mitchell Kennerley, Bookman, p. 40-41.

[3] For more on Wilde’s sometimes dismissive source acknowledgements see Josephine Guy’s discussion of “Pen, Pencil and Poison” in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, volume 4: Criticism, pp. 411–12, n.12–13.

[4] Schroeder hypothesizes that this hesitancy stemmed from Wilde being scandalized by the publication of Hichens’s The Green Carnation, and perhaps Lane also took offense at his name being used as the butler in “The Importance of Being Earnest” (Composition 32-33). Furthermore, Ian Small mentioned the fact that Lane claims not to have seen the manuscript at this point, indicating that perhaps Wilde had plans to revise it further (“Introduction” lxxi).

[5] Kennerley was working closely with his cousin Arthur Hooley. See John Sloan’s “‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.’ The Rosenbach Manuscript Examined,” p.39.

[6] For more on Wilde’s interest in the political career of Charles Stewart Parnell, see Matthew Sturgis, Oscar: A Life, p. 382-3.

[7] Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas—speaking for Wilde without his consent—insisted that Wilde did subscribe to the Willie Hughes explanation of the Sonnets. See G. Wilson Knight, The Mutual Flame: On Shakespeare's Sonnets and the Phoenix and the Turtle, p.7.

[8] See Oscar Wilde, “The Truth of Masks.” p. 1173.